Phoenician city-states, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c5/Phoenicia_map-en.svg/250px-Phoenicia_map-en.svg.png

Phoenician city-states, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c5/Phoenicia_map-en.svg/250px-Phoenicia_map-en.svg.png

Chapter 3

Migration and Empire: the Spread of Civilization

Section 4 Kingdoms and City-States in Southwest Asia

While great empires rose and fell in Egypt and Mesopotamia, smaller kingdoms began consolidating in the Levant, the region along the eastern Mediterranean Sea. These small kingdoms, with their scant resources and hostile neighbors, left legacies to the modern world that are felt even today. The modern alphabet, coined money, and one of the world’s major religions had their origins in the small kingdoms of the Levant.

The Phoenicians

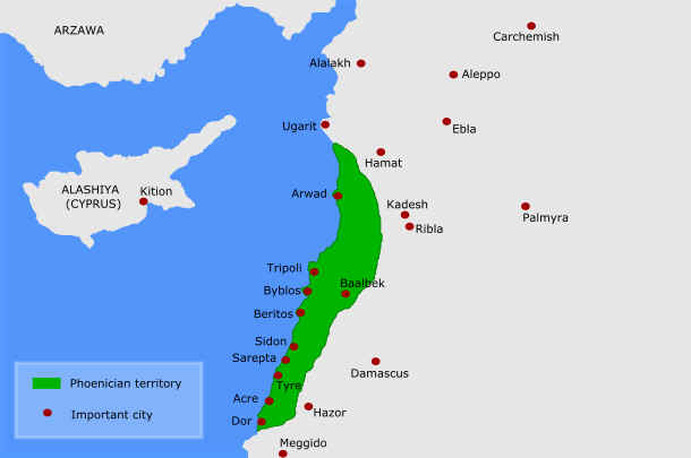

As the great waves of nomadic invasion battered and brought down empires in southwest Asia, new states began to emerge in their border regions. After the collapse of Minoan and Mycenaean trade in the eastern Mediterranean, for example, the Phoenicians, a Semitic-speaking people from the eastern Mediterranean coast, emerged to fill the void.

Beginning perhaps as early as the third millennium B.C., the ancestors of the Phoenicians, Semitic-speaking people who referred to themselves as “Canaanites,” had settled in small city-states in the coastal regions of modern-day Lebanon, Syria and Israel. Eventually, some would spread as far south as Gaza. Hemmed in by the Mediterranean Sea and the Lebanon Mountains, these city-states, separated by the hills that ran from the mountains to the sea, had few natural resources. Agriculture was difficult, though they were able to herd some sheep. With such meager land resources, these early Phoenicians adapted to the sea in order to survive. They developed fast, seaworthy ships rowed by two tiers of oarsmen. Their ships gave them an advantage in overseas commerce and by 1500 B.C. the Phoenicians had established a lively trade with Egypt.

Migration and Empire: the Spread of Civilization

Section 4 Kingdoms and City-States in Southwest Asia

While great empires rose and fell in Egypt and Mesopotamia, smaller kingdoms began consolidating in the Levant, the region along the eastern Mediterranean Sea. These small kingdoms, with their scant resources and hostile neighbors, left legacies to the modern world that are felt even today. The modern alphabet, coined money, and one of the world’s major religions had their origins in the small kingdoms of the Levant.

The Phoenicians

As the great waves of nomadic invasion battered and brought down empires in southwest Asia, new states began to emerge in their border regions. After the collapse of Minoan and Mycenaean trade in the eastern Mediterranean, for example, the Phoenicians, a Semitic-speaking people from the eastern Mediterranean coast, emerged to fill the void.

Beginning perhaps as early as the third millennium B.C., the ancestors of the Phoenicians, Semitic-speaking people who referred to themselves as “Canaanites,” had settled in small city-states in the coastal regions of modern-day Lebanon, Syria and Israel. Eventually, some would spread as far south as Gaza. Hemmed in by the Mediterranean Sea and the Lebanon Mountains, these city-states, separated by the hills that ran from the mountains to the sea, had few natural resources. Agriculture was difficult, though they were able to herd some sheep. With such meager land resources, these early Phoenicians adapted to the sea in order to survive. They developed fast, seaworthy ships rowed by two tiers of oarsmen. Their ships gave them an advantage in overseas commerce and by 1500 B.C. the Phoenicians had established a lively trade with Egypt.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9c/PhoenicianTrade.png/325px-PhoenicianTrade.png

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9c/PhoenicianTrade.png/325px-PhoenicianTrade.png

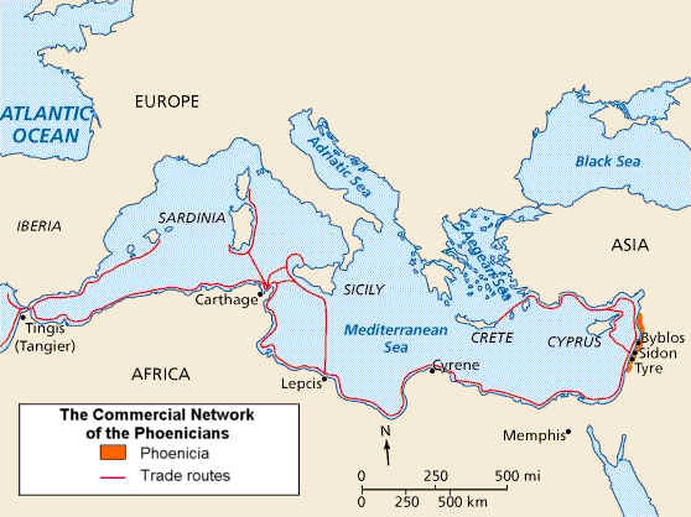

With the collapse of Cretan and Mycenaean power and the depredations of the Sea peoples around 1200, the Phoenicians expanded rapidly. By about 900 B.C., they dominated trade in the Mediterranean, carrying goods as far away as Cornwall in southwest England. The Phoenicians created beautiful jewelry and highly prized furniture, but above all they were known for their dyes and textiles, particularly a reddish-purple color that became known as Tyrian purple, from the city of Tyre. It was this latter association that caused the Greeks to call them Phoiniki, or “Purple People,” (hence the name Phoenician, as well as the “phoenix,” referring to the supposedly colorful plumage of the mythical bird.) Their ships not only carried their own products, however, but also goods from all over the ancient world. To facilitate such trading activities, they established numerous trading colonies in the western Mediterranean and on the North African coast, the most famous of which was Carthage.

Phoenicia began to decline in strength in the 800s B.C., when the Assyrians conquered many Phoenician city-states. By 538 B.C., Phoenicia had lost its independence completely as it fell under the control of the Persians.Its colonies in the western Mediterranean, however, continued to flourish and expand—particularly Carthage, which soon had an empire of its own.

Phoenicia began to decline in strength in the 800s B.C., when the Assyrians conquered many Phoenician city-states. By 538 B.C., Phoenicia had lost its independence completely as it fell under the control of the Persians.Its colonies in the western Mediterranean, however, continued to flourish and expand—particularly Carthage, which soon had an empire of its own.

Ugarit and the First Alphabet

As Phoenicians traveled, they took with them their 22-character alphabet, which they used primarily for record keeping. Unlike the other writing systems of Mesopotamia and Egypt, the Phoenician script was a true alphabet—each symbol represented a particular sound rather than a word or an idea. The Greeks adopted this alphabet, which later developed into our modern alphabet. Although for many years the Phoenicians were credited with having developed the first true alphabet, the discovery and subsequent excavation of the ancient city of Ugarit along the Syrian coast in 1928 have made it clear that the Phoenicians were actually heirs to an earlier tradition.

Originally settled as early as 6000 B.C. as a Neolithic town, Ugarit became an important center of culture and learning. Its discovery has been especially important for our understanding of the late Bronze Age: the city contained no less than three official libraries and two private libraries (the only ones so far found in the ancient world) containing altogether several thousand cuneiform tablets. From these sources it is clear that the rulers of Ugarit were in contact with all the major powers of Southwest Asia and the Aegean – the Hittites, Egyptians, Minoans and Mycenaeans. The literary volumes that have been translated cast enormous light on the origins of Hebrew literature and the Bible itself. It is also clear from these finds that the scribes of Ugarit developed the first alphabet, derived from cuneiform, about 500 years earlier than the Phoenician version. Ugaritic, a Semitic language closely related to Hebrew, was written with an alphabet of some thirty letters:

Like so many other states and cities along the eastern Mediterranean coast, Ugarit finally fell prey to the Sea Peoples in the violent upheavals of the 1200s B.C. and never recovered. Its alphabetic and literary traditions, however, lived on through related Semitic-speaking peoples, the Phoenicians and the Hebrews.

As Phoenicians traveled, they took with them their 22-character alphabet, which they used primarily for record keeping. Unlike the other writing systems of Mesopotamia and Egypt, the Phoenician script was a true alphabet—each symbol represented a particular sound rather than a word or an idea. The Greeks adopted this alphabet, which later developed into our modern alphabet. Although for many years the Phoenicians were credited with having developed the first true alphabet, the discovery and subsequent excavation of the ancient city of Ugarit along the Syrian coast in 1928 have made it clear that the Phoenicians were actually heirs to an earlier tradition.

Originally settled as early as 6000 B.C. as a Neolithic town, Ugarit became an important center of culture and learning. Its discovery has been especially important for our understanding of the late Bronze Age: the city contained no less than three official libraries and two private libraries (the only ones so far found in the ancient world) containing altogether several thousand cuneiform tablets. From these sources it is clear that the rulers of Ugarit were in contact with all the major powers of Southwest Asia and the Aegean – the Hittites, Egyptians, Minoans and Mycenaeans. The literary volumes that have been translated cast enormous light on the origins of Hebrew literature and the Bible itself. It is also clear from these finds that the scribes of Ugarit developed the first alphabet, derived from cuneiform, about 500 years earlier than the Phoenician version. Ugaritic, a Semitic language closely related to Hebrew, was written with an alphabet of some thirty letters:

Like so many other states and cities along the eastern Mediterranean coast, Ugarit finally fell prey to the Sea Peoples in the violent upheavals of the 1200s B.C. and never recovered. Its alphabetic and literary traditions, however, lived on through related Semitic-speaking peoples, the Phoenicians and the Hebrews.

The Lydians

The ancient country of Lydia, located in Asia Minor, was famous for its rich mineral deposits, particularly gold. Like Phoenicia, Lydia based its economy on trade. However, they found that bartering, or exchanging one product or service for another, was often problematic when both traders could not agree on the goods or services to trade. The Lydians solved this problem in about 600 B.C., when they made coins of gold, or money. The use of money allowed traders to set prices for various goods and services. Therefore, the Lydians developed a money economy, an economic system based on the use of money rather than on barter.

The Lydians were not empire builders. In 545 B.C., the Persians conquered Lydia and discovered the great wealth of the last Lydian king, Croesus (cree-suhs). Although Lydia did not make a great political impact on the world, their concept of a money economy spread to the Greeks and the Persians, who in turn helped spread this concept to other parts of the world.

The Philistines

While the Phoenicians emerged during the great age of migrations and took to the sea, further south along the eastern Mediterranean coast another migrant people, the Philistines, began to settle the land. In the 1200s and 1100s B.C., the Philistines had been one of the so-called Sea Peoples who terrorized eastern Mediterranean civilizations by land and by sea. In an alliance with other Sea Peoples, they invaded and devastated the Hittite empire before moving through the Levant toward Egypt, where the pharaoh Ramses III stopped them.

The Philistines, like the other Sea Peoples, were part of the great second wave of migration that wrought so much havoc in southwest Asia around 1200. They were not simply raiders, however, for they brought their families with them as they moved. By the 1100s B.C., many of these families had settled on the coast of Canaan, in present-day Israel. For a time, it seems, the Egyptians actually hired some Philistines as mercenaries to control the outlying regions of the empire. Before long, however, the Philistines in the Egyptian army grew strong enough to take control of Canaan for themselves. Apparently, the Philistines were the only ones in the region with knowledge of iron, which gave them a dramatic advantage in warfare. With this advantage they soon established their rule over the Canaanites.

Once they had gained control over Canaan, the Philistines settled down and began to build substantial, well-planned cities. They became famous for their remarkable ceramic ware and over time they built a prosperous trade with Egypt, Phoenicia, and Cyprus. Their prosperity and their military skill encouraged them to exert control over surrounding peoples, many of whom were also on the move in the region. One of these groups was the Hebrews, yet another group of Semitic-speaking peoples who had migrated into Canaan.

The ancient country of Lydia, located in Asia Minor, was famous for its rich mineral deposits, particularly gold. Like Phoenicia, Lydia based its economy on trade. However, they found that bartering, or exchanging one product or service for another, was often problematic when both traders could not agree on the goods or services to trade. The Lydians solved this problem in about 600 B.C., when they made coins of gold, or money. The use of money allowed traders to set prices for various goods and services. Therefore, the Lydians developed a money economy, an economic system based on the use of money rather than on barter.

The Lydians were not empire builders. In 545 B.C., the Persians conquered Lydia and discovered the great wealth of the last Lydian king, Croesus (cree-suhs). Although Lydia did not make a great political impact on the world, their concept of a money economy spread to the Greeks and the Persians, who in turn helped spread this concept to other parts of the world.

The Philistines

While the Phoenicians emerged during the great age of migrations and took to the sea, further south along the eastern Mediterranean coast another migrant people, the Philistines, began to settle the land. In the 1200s and 1100s B.C., the Philistines had been one of the so-called Sea Peoples who terrorized eastern Mediterranean civilizations by land and by sea. In an alliance with other Sea Peoples, they invaded and devastated the Hittite empire before moving through the Levant toward Egypt, where the pharaoh Ramses III stopped them.

The Philistines, like the other Sea Peoples, were part of the great second wave of migration that wrought so much havoc in southwest Asia around 1200. They were not simply raiders, however, for they brought their families with them as they moved. By the 1100s B.C., many of these families had settled on the coast of Canaan, in present-day Israel. For a time, it seems, the Egyptians actually hired some Philistines as mercenaries to control the outlying regions of the empire. Before long, however, the Philistines in the Egyptian army grew strong enough to take control of Canaan for themselves. Apparently, the Philistines were the only ones in the region with knowledge of iron, which gave them a dramatic advantage in warfare. With this advantage they soon established their rule over the Canaanites.

Once they had gained control over Canaan, the Philistines settled down and began to build substantial, well-planned cities. They became famous for their remarkable ceramic ware and over time they built a prosperous trade with Egypt, Phoenicia, and Cyprus. Their prosperity and their military skill encouraged them to exert control over surrounding peoples, many of whom were also on the move in the region. One of these groups was the Hebrews, yet another group of Semitic-speaking peoples who had migrated into Canaan.

The Hebrews

Of all the peoples living in the Levant, the Hebrews made perhaps the greatest and longest-lasting impact on the world because of their religious ideas. Like other Semitic-speaking peoples, they were originally nomadic pastoralists living in the desert grasslands around the Fertile Crescent. Most of what we know about them comes from their own later writings. These records contained not only their laws and the requirements of their religion, but also the traditional accounts of much of their early history. These writings later became the foundation for both the Jewish Torah and the Christian Bible.

According to these traditional accounts, a shepherd named Abraham, who originally lived in Sumer, founded the Hebrew people. Abraham left his home in Sumer and migrated with his entire family to the land of Canaan. His son Jacob—also known as Israel—had 12 sons. During the early years of their history, the Hebrew people traced their descent to one of Jacob’s sons, and thus became known as the Twelve Tribes of Israel. When famine struck the Hebrews in Canaan, however, some apparently moved to Egypt, where they lived peacefully for some time. According to the biblical account, however, eventually the Hebrews in Egypt became slaves of pharaoh and lived “in bondage” for centuries. Their way of life changed dramatically, and their ancient laws fell into disuse.

Establishing a homeland. Sometime in the 1200s B.C., a leader named Moses led the Hebrew tribes out of Egypt and into the desert of the Sinai Peninsula. This flight from Egypt, called the Exodus, is commemorated in the Jewish festival of Passover. After the Exodus, according to the biblical account, Moses climbed Mount Sinai and returned bearing stone tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments—the moral laws revealed to him by the Hebrew god Yahweh (yah-way). The commandments emphasized the importance of the family, human life, formal worship, self-restraint, and justice. They also taught a moral system of behavior, in which people should deal honestly and fairly with one another. For example, lying and stealing were prohibited. When the people following Moses agreed to follow these laws, the Hebrews later taught, they had entered a covenant, or solemn agreement, with God, whom they now accepted as their divine guardian and supreme authority.

Moses believed that Canaan was a promised land and that Yahweh had instructed him to create a holy nation. Inspired by his words, the Hebrews set out for Canaan. According to the Bible, Moses and his followers wandered in the desert for many years before they reached Canaan. From their entry into Canaan, the Hebrews became known as Israelites. However, establishing a homeland in Canaan was not easy. The 12 tribes were not unified, which made their struggle against the peoples living in Canaan more difficult. The Canaanites and Philistines vigorously defended their territories in a struggle that lasted for centuries. The Israelites conquered the Canaanites, but they were unable to completely conquer the Philistines.

A new government and customs. After long years of fighting the Philistines and Canaanites, the Hebrew tribes finally united under one king, Saul. During his reign and those of his successors, David and Solomon, the kingdom of Israel grew in size and power. David captured Jerusalem and made it the capital of his kingdom. Later, David’s son Solomon built a magnificent temple to Yahweh in Jerusalem. The temple served as the center of religious life and became a powerful symbol of the Israelites' unity.

Religion and government of the Israelites were closely linked. At his coronation, the king made a covenant with his people. He agreed to lead them justly, in exchange for their submission to his authority. This covenant was similar to the one the Hebrew people had made with Yahweh, as proceedings at David’s coronation showed:

Jehoida [the priest] solemnized the covenant between the Lord, on the one hand, and the king and the people, on the other—as well as between the king and the people—that they should be the people of the Lord.

As long as the king honored this covenant and obeyed the laws of Moses, he could not exercise unlimited power over the Hebrew people.

The Old Testament. During this time, the teachings of Moses were first written down. These five books, known as the Torah, later became the first five books of the Old Testament. Mosaic Law included the Ten Commandments as well as laws developed during later periods. Mosaic law, like the Code of Hammurabi, demanded “an eye for an eye,” but it set a much higher value on human life. For example, although slavery was acceptable under Mosaic law, the law demanded kindness for slaves.

Other books of the Old Testament tell the history of the Hebrews. Beginning with the Hebrews’ belief in the creation of the world, the Old Testament describes the special mission of the Israelites, their escape from slavery in Egypt, and the progress of their history and beliefs. The rest of the Old Testament includes poetry, religious instruction, prophecy, and laws.

The divided kingdom. After Solomon died in 922 B.C., the 10 northern tribes revolted and the kingdom was divided into two parts. The northern part became the kingdom of Israel, with its capital at Samaria. The southern part, situated around the Dead Sea, became the kingdom of Judah, with Jerusalem as its capital. Despite the political division, however, the Hebrews continued to think of themselves as one people, descended from Abraham.

These two Hebrew kingdoms were not strong enough to withstand invasions from the east. As part of their sweep across the Middle East, the Assyrians conquered the kingdom of Israel about 722 B.C., capturing many Israelites and deporting them to Assyria to serve as slaves. Most of those who remained in Israel scattered among the other peoples of the region. No longer living as a separate people, they became known as the ten lost tribes.

In 587 B.C., the Chaldean king Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon captured the kingdom of Judah and destroyed Jerusalem. The Chaldeans destroyed Solomon’s temple and took many of the southern Israelites into captivity. This period is known as the Babylonian Captivity. Unlike the tribes of the northern kingdom, however, the people of Judah maintained their religion and separate identity. From the Babylonian Captivity, the Israelites became known as Jews, since the people of the kingdom of Judah were the ones who maintained their religious and cultural traditions.

In 539 B.C., the Persian king Cyrus conquered Babylonia. Seeing himself as a liberator of those peoples who had been oppressed by the Babylonians, he allowed those Jews who wanted to return to Judah to do so and even gave them support for the rebuilding of their temple in Jerusalem. Over the next several decades, at least three large groups did return to Jerusalem under the leadership of Zerubbabel, a descendant of the next to last king of Judah, and several other prophets and members of the old priesthood. Zerubbabel, who acted as governor of Judah under the Persian monarch, began the rebuilding of the Temple. Even so, many Jews remained in Babylon and scattered throughout the other parts of the empire in what became known as the Diaspora; Jewish communities have lived scattered throughout the world ever since.

As subjects of the Persian Empire, for nearly two centuries the returned exiles lived in relative peace and autonomy. In place of the monarchy, which was never revived, at first they were led by men they recognized as prophets, particularly Haggai, Zacchariah and Malachi, who oversaw the restoration of the Temple. Malachi, however, was the last to be generally recognized as a prophet. After his death, the community was ruled by pairs of leaders, known as zugot, made up of the High Priest and his deputy. These two men were also the president and vice president respectively of the central religious law court, the Sanhedrin, which was comprised of 71 elders.

According to some scholars, it was during this Second Temple period, as the era became known, that several different groups emerged within the Jewish community with rather different ideas about the nature and practices of their religion and the core identity of the nation. Jewish identity increasingly revolved around two things - the ceremonies of worship in the Temple; and the development and application of Torah, the "Teachings" of Moses, as the Law that governed all aspects of Jewish life. At first, the Temple priests constituted a kind of ruling aristocracy over the rest of the people. Some of the returned Jews, however, apparently blamed the old Temple priesthood for the calamity that had befallen the nation with the Babylonian conquest. Rather than simply returning to the old ways, with the priests as a hereditary caste in charge of all religious life, these religious reformers began to emphasize the importance of the Mosaic law and of prayer, rather than the blood sacrifices performed by the priests of the Temple, as the identifying features of the faith.

Judaism. Judaism, the religion that developed out of the experiences and early religious traditions of the ancient Hebrews and their descendants, survived partly because it adapted to changing circumstances. Unlike the local deities of other cultures, the Hebrew god did not belong to a specific place. The early Hebrews worshiped Yahweh as a god who belonged to them alone, wherever they happened to live. They viewed Yahweh not only as their protector and provider, but also as a god to fear. If people sinned against him, not only would they be punished, but their children and succeeding generations would also suffer.

These original conceptions about the nature of their god, however, changed over time and reflected the historical experiences of the early Hebrews. At first, apparently, they did not necessarily see Yahweh as the only god – He was simply their particular god. Gradually, however, this concept of Yahweh changed, partly because of the suffering of the Israelites and partly because of the teachings of their prophets. By the time of the establishment of the Hebrew kingdom, and particularly during its period of imperial conquest and expansion under Solomon, the Hebrews had come to believe that their god was the only true God, the Creator and sovereign of the universe, and that all the various gods believed in by other peoples were false gods, either non-existent or demonic. The experience of the Babylonian captivity and life under the Persian Empire also seems to have influenced the Hebrew prophets as it exposed them to the ethical and moral teachings of Zoroastrianism. It was particularly after the return from exile that the prophets began to emphasize that Yahweh was more concerned with moral behavior than with religious rituals; that people had a choice between good and evil and that Yahweh held them responsible for their choices.

Of all the peoples living in the Levant, the Hebrews made perhaps the greatest and longest-lasting impact on the world because of their religious ideas. Like other Semitic-speaking peoples, they were originally nomadic pastoralists living in the desert grasslands around the Fertile Crescent. Most of what we know about them comes from their own later writings. These records contained not only their laws and the requirements of their religion, but also the traditional accounts of much of their early history. These writings later became the foundation for both the Jewish Torah and the Christian Bible.

According to these traditional accounts, a shepherd named Abraham, who originally lived in Sumer, founded the Hebrew people. Abraham left his home in Sumer and migrated with his entire family to the land of Canaan. His son Jacob—also known as Israel—had 12 sons. During the early years of their history, the Hebrew people traced their descent to one of Jacob’s sons, and thus became known as the Twelve Tribes of Israel. When famine struck the Hebrews in Canaan, however, some apparently moved to Egypt, where they lived peacefully for some time. According to the biblical account, however, eventually the Hebrews in Egypt became slaves of pharaoh and lived “in bondage” for centuries. Their way of life changed dramatically, and their ancient laws fell into disuse.

Establishing a homeland. Sometime in the 1200s B.C., a leader named Moses led the Hebrew tribes out of Egypt and into the desert of the Sinai Peninsula. This flight from Egypt, called the Exodus, is commemorated in the Jewish festival of Passover. After the Exodus, according to the biblical account, Moses climbed Mount Sinai and returned bearing stone tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments—the moral laws revealed to him by the Hebrew god Yahweh (yah-way). The commandments emphasized the importance of the family, human life, formal worship, self-restraint, and justice. They also taught a moral system of behavior, in which people should deal honestly and fairly with one another. For example, lying and stealing were prohibited. When the people following Moses agreed to follow these laws, the Hebrews later taught, they had entered a covenant, or solemn agreement, with God, whom they now accepted as their divine guardian and supreme authority.

Moses believed that Canaan was a promised land and that Yahweh had instructed him to create a holy nation. Inspired by his words, the Hebrews set out for Canaan. According to the Bible, Moses and his followers wandered in the desert for many years before they reached Canaan. From their entry into Canaan, the Hebrews became known as Israelites. However, establishing a homeland in Canaan was not easy. The 12 tribes were not unified, which made their struggle against the peoples living in Canaan more difficult. The Canaanites and Philistines vigorously defended their territories in a struggle that lasted for centuries. The Israelites conquered the Canaanites, but they were unable to completely conquer the Philistines.

A new government and customs. After long years of fighting the Philistines and Canaanites, the Hebrew tribes finally united under one king, Saul. During his reign and those of his successors, David and Solomon, the kingdom of Israel grew in size and power. David captured Jerusalem and made it the capital of his kingdom. Later, David’s son Solomon built a magnificent temple to Yahweh in Jerusalem. The temple served as the center of religious life and became a powerful symbol of the Israelites' unity.

Religion and government of the Israelites were closely linked. At his coronation, the king made a covenant with his people. He agreed to lead them justly, in exchange for their submission to his authority. This covenant was similar to the one the Hebrew people had made with Yahweh, as proceedings at David’s coronation showed:

Jehoida [the priest] solemnized the covenant between the Lord, on the one hand, and the king and the people, on the other—as well as between the king and the people—that they should be the people of the Lord.

As long as the king honored this covenant and obeyed the laws of Moses, he could not exercise unlimited power over the Hebrew people.

The Old Testament. During this time, the teachings of Moses were first written down. These five books, known as the Torah, later became the first five books of the Old Testament. Mosaic Law included the Ten Commandments as well as laws developed during later periods. Mosaic law, like the Code of Hammurabi, demanded “an eye for an eye,” but it set a much higher value on human life. For example, although slavery was acceptable under Mosaic law, the law demanded kindness for slaves.

Other books of the Old Testament tell the history of the Hebrews. Beginning with the Hebrews’ belief in the creation of the world, the Old Testament describes the special mission of the Israelites, their escape from slavery in Egypt, and the progress of their history and beliefs. The rest of the Old Testament includes poetry, religious instruction, prophecy, and laws.

The divided kingdom. After Solomon died in 922 B.C., the 10 northern tribes revolted and the kingdom was divided into two parts. The northern part became the kingdom of Israel, with its capital at Samaria. The southern part, situated around the Dead Sea, became the kingdom of Judah, with Jerusalem as its capital. Despite the political division, however, the Hebrews continued to think of themselves as one people, descended from Abraham.

These two Hebrew kingdoms were not strong enough to withstand invasions from the east. As part of their sweep across the Middle East, the Assyrians conquered the kingdom of Israel about 722 B.C., capturing many Israelites and deporting them to Assyria to serve as slaves. Most of those who remained in Israel scattered among the other peoples of the region. No longer living as a separate people, they became known as the ten lost tribes.

In 587 B.C., the Chaldean king Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon captured the kingdom of Judah and destroyed Jerusalem. The Chaldeans destroyed Solomon’s temple and took many of the southern Israelites into captivity. This period is known as the Babylonian Captivity. Unlike the tribes of the northern kingdom, however, the people of Judah maintained their religion and separate identity. From the Babylonian Captivity, the Israelites became known as Jews, since the people of the kingdom of Judah were the ones who maintained their religious and cultural traditions.

In 539 B.C., the Persian king Cyrus conquered Babylonia. Seeing himself as a liberator of those peoples who had been oppressed by the Babylonians, he allowed those Jews who wanted to return to Judah to do so and even gave them support for the rebuilding of their temple in Jerusalem. Over the next several decades, at least three large groups did return to Jerusalem under the leadership of Zerubbabel, a descendant of the next to last king of Judah, and several other prophets and members of the old priesthood. Zerubbabel, who acted as governor of Judah under the Persian monarch, began the rebuilding of the Temple. Even so, many Jews remained in Babylon and scattered throughout the other parts of the empire in what became known as the Diaspora; Jewish communities have lived scattered throughout the world ever since.

As subjects of the Persian Empire, for nearly two centuries the returned exiles lived in relative peace and autonomy. In place of the monarchy, which was never revived, at first they were led by men they recognized as prophets, particularly Haggai, Zacchariah and Malachi, who oversaw the restoration of the Temple. Malachi, however, was the last to be generally recognized as a prophet. After his death, the community was ruled by pairs of leaders, known as zugot, made up of the High Priest and his deputy. These two men were also the president and vice president respectively of the central religious law court, the Sanhedrin, which was comprised of 71 elders.

According to some scholars, it was during this Second Temple period, as the era became known, that several different groups emerged within the Jewish community with rather different ideas about the nature and practices of their religion and the core identity of the nation. Jewish identity increasingly revolved around two things - the ceremonies of worship in the Temple; and the development and application of Torah, the "Teachings" of Moses, as the Law that governed all aspects of Jewish life. At first, the Temple priests constituted a kind of ruling aristocracy over the rest of the people. Some of the returned Jews, however, apparently blamed the old Temple priesthood for the calamity that had befallen the nation with the Babylonian conquest. Rather than simply returning to the old ways, with the priests as a hereditary caste in charge of all religious life, these religious reformers began to emphasize the importance of the Mosaic law and of prayer, rather than the blood sacrifices performed by the priests of the Temple, as the identifying features of the faith.

Judaism. Judaism, the religion that developed out of the experiences and early religious traditions of the ancient Hebrews and their descendants, survived partly because it adapted to changing circumstances. Unlike the local deities of other cultures, the Hebrew god did not belong to a specific place. The early Hebrews worshiped Yahweh as a god who belonged to them alone, wherever they happened to live. They viewed Yahweh not only as their protector and provider, but also as a god to fear. If people sinned against him, not only would they be punished, but their children and succeeding generations would also suffer.

These original conceptions about the nature of their god, however, changed over time and reflected the historical experiences of the early Hebrews. At first, apparently, they did not necessarily see Yahweh as the only god – He was simply their particular god. Gradually, however, this concept of Yahweh changed, partly because of the suffering of the Israelites and partly because of the teachings of their prophets. By the time of the establishment of the Hebrew kingdom, and particularly during its period of imperial conquest and expansion under Solomon, the Hebrews had come to believe that their god was the only true God, the Creator and sovereign of the universe, and that all the various gods believed in by other peoples were false gods, either non-existent or demonic. The experience of the Babylonian captivity and life under the Persian Empire also seems to have influenced the Hebrew prophets as it exposed them to the ethical and moral teachings of Zoroastrianism. It was particularly after the return from exile that the prophets began to emphasize that Yahweh was more concerned with moral behavior than with religious rituals; that people had a choice between good and evil and that Yahweh held them responsible for their choices.