Chapter 1

Before Civilization

"In the beginning human history is a great darkness." This observation, made half a century ago by a leading world historian, is still true today. Despite great efforts on the part of historians, anthropologists, paleontologists, and numerous other scholars over the years, we are still forced to re-construct the story of early human beings from very little evidence. It is a story that depends upon little more than a basketful of human skeletal bones and other fossils, the remains of once living matter, as well as the artifacts, or man-made objects, that have been found buried with them.

Section 1 The Rise of Humanity

Stones that have been chipped and shaped, slivers of sharpened bone, bits and pieces of old pots, these are the kinds of clues that scholars and scientists try to put together to understand humanity's deep past. As might be expected, with so little evidence, there are frequent disagreements among experts on how the pieces fit together and what the puzzle means. The lack of evidence should not surprise us, however, for we are talking about creatures who lived and died between about 4,000,000 years ago and 30,000 years ago.

Taken from http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/comdesc/hominids.html

EARLY HOMINIDS

The origins of humanity are much disputed. As far as we can tell now, the first human-like creatures, or hominids, began to walk upright on the face of the earth between three and four million years ago. Anthropologists, scientists who specialize in investigating the origins and development of the human species, tell us that in those faraway days at the dawn of human history several different types of hominids roamed the African savanna - vast, open grasslands dotted with trees and scattered underbrush. The earliest remains of such creatures have been found in east, northeast and southern Africa, and are members of the species called Australopithecus, or Southern Ape.

There seem to have been two types of Australopithecus, one that averaged about four feet in height and a larger one that averaged about five feet. Both types walked upright, but their brains were only about one-third as big as that of a modern human being. Many scientists believed that the smaller version may have been the basic stock from which early human beings developed.

In 1975, however, a leading anthropologist, Mary Leakey, discovered the jaws and teeth of what appeared to be an early human near the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, East Africa. Different from Australopithecus, these human remains dated from about 3.75 million years ago, the oldest ever found. The same year, two other scientists working in Ethiopia, an American, Donald Johanson, and a Frenchman, Maurice Taieb, announced a find they had made the previous year: the oldest Australopithecine remains yet found, those of a young female whom Johanson promptly named "Lucy" (after the recent hit song by the Beatles, "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds"). Lucy too was over 3 million years old. These two finds taken together suggested that Australopithecus was not a direct ancestor of humanity, but rather a species that survived alongside the predecessors of modern human beings.

Smaller than modern human beings, and with considerably smaller brain capacities, these early species were nevertheless similar to us in some important ways. For example, they learned to use simple tools of stone and wood. They apparently learned to cooperate with one another in finding food, particularly in hunting small animals. They also probably developed some form of language as a means of communication. It is even possible, though the evidence is sketchy, that some of them may have learned to use and control fire.

These hominids lived on the earth much longer than modern humankind, for the traces we have found of them span several million years. By about 250,000 years ago, however, when the first biologically modern types of human beings had begun to appear in small, scattered hunting bands, these earlier hominids had begun to disappear from the planet. The reason, as with the periodic disappearance of other species, seems to have been a failure to adapt rapidly enough to a changing environment.

WEB RESOURCE: How to Make a Human Being

Before Civilization

"In the beginning human history is a great darkness." This observation, made half a century ago by a leading world historian, is still true today. Despite great efforts on the part of historians, anthropologists, paleontologists, and numerous other scholars over the years, we are still forced to re-construct the story of early human beings from very little evidence. It is a story that depends upon little more than a basketful of human skeletal bones and other fossils, the remains of once living matter, as well as the artifacts, or man-made objects, that have been found buried with them.

Section 1 The Rise of Humanity

Stones that have been chipped and shaped, slivers of sharpened bone, bits and pieces of old pots, these are the kinds of clues that scholars and scientists try to put together to understand humanity's deep past. As might be expected, with so little evidence, there are frequent disagreements among experts on how the pieces fit together and what the puzzle means. The lack of evidence should not surprise us, however, for we are talking about creatures who lived and died between about 4,000,000 years ago and 30,000 years ago.

Taken from http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/comdesc/hominids.html

EARLY HOMINIDS

The origins of humanity are much disputed. As far as we can tell now, the first human-like creatures, or hominids, began to walk upright on the face of the earth between three and four million years ago. Anthropologists, scientists who specialize in investigating the origins and development of the human species, tell us that in those faraway days at the dawn of human history several different types of hominids roamed the African savanna - vast, open grasslands dotted with trees and scattered underbrush. The earliest remains of such creatures have been found in east, northeast and southern Africa, and are members of the species called Australopithecus, or Southern Ape.

There seem to have been two types of Australopithecus, one that averaged about four feet in height and a larger one that averaged about five feet. Both types walked upright, but their brains were only about one-third as big as that of a modern human being. Many scientists believed that the smaller version may have been the basic stock from which early human beings developed.

In 1975, however, a leading anthropologist, Mary Leakey, discovered the jaws and teeth of what appeared to be an early human near the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, East Africa. Different from Australopithecus, these human remains dated from about 3.75 million years ago, the oldest ever found. The same year, two other scientists working in Ethiopia, an American, Donald Johanson, and a Frenchman, Maurice Taieb, announced a find they had made the previous year: the oldest Australopithecine remains yet found, those of a young female whom Johanson promptly named "Lucy" (after the recent hit song by the Beatles, "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds"). Lucy too was over 3 million years old. These two finds taken together suggested that Australopithecus was not a direct ancestor of humanity, but rather a species that survived alongside the predecessors of modern human beings.

Smaller than modern human beings, and with considerably smaller brain capacities, these early species were nevertheless similar to us in some important ways. For example, they learned to use simple tools of stone and wood. They apparently learned to cooperate with one another in finding food, particularly in hunting small animals. They also probably developed some form of language as a means of communication. It is even possible, though the evidence is sketchy, that some of them may have learned to use and control fire.

These hominids lived on the earth much longer than modern humankind, for the traces we have found of them span several million years. By about 250,000 years ago, however, when the first biologically modern types of human beings had begun to appear in small, scattered hunting bands, these earlier hominids had begun to disappear from the planet. The reason, as with the periodic disappearance of other species, seems to have been a failure to adapt rapidly enough to a changing environment.

WEB RESOURCE: How to Make a Human Being

ENVIRONMENTAL ADAPTATION

All life depends upon its ability to draw sustenance from its surroundings. For land animals this means air, water and food (including essential elements such as salt), and perhaps shelter. Creatures survive only when they have the physical characteristics and skills needed to obtain these requirements. If the environment changes suddenly, then the characteristics and skills required to continuing extracting the necessary resources may have to change as well.

For example, animals living in a warm climate do not need heavy fur to keep them warm. But if the weather changes and becomes much colder they must adjust to the new temperature or risk freezing to death. Changing climate may also prevent the foods on which they have depended from being able to grow. They must either learn to eat different kinds of foods, which can grow in the new climate, or move away in search of climates where their natural food supply does still grow. The process of making these adjustments to the changing environment in order to survive is called environmental adaptation. What really separated modern humans from their hominid predecessors were the means by which they practiced environmental adaptation.

Early hominids, and perhaps even early human populations, depended for survival primarily on evolution, a process of biological adaptation to their environments. Biological adaptation is the process by which the physical characteristics of a species change over time. Much misunderstood, and still disputed by many scholars, the idea of how species, including humanity, change, was the subject of Charles Darwin's investigations in the 1800s.

As far as scientists can tell now, evolution occurs through sudden changes, called mutations, in the genetic structure of particular individuals. Genes are tiny particles within the physical body, organized in structures called chromosomes, and carried in the reproductive cells of the body. Genes provide the blueprint from which the body itself develops through life. If the genetic structure of a body is somehow changed, then so too will be the information that governs its physical development. When such genetic changes occur, they show up in the form of new physical or mental traits in the next generation. Genetic mutations can be caused by many things. Malnutrition, for example, can cause chromosomal damage. Also, we know that exposure to certain types of radiation, such as extreme sunlight or radioactive materials like uranium and plutonium, as well as exposure to certain man-made and even some naturally occurring chemicals may often cause genetic damage. Even so, we still do not fully understand all the causes of genetic mutation from one generation to the next. Consequently, whether such changes are entirely random or subject to some larger pattern in the universe is a matter of considerable debate.

Although most mutations seem to have negative results, often lessening the chances for survival of those that are affected by them, occasionally the opposite is true. Sometimes, these new, inherited characteristics may give individuals a better chance of adapting to a changing environment than the other members of their species. Being able to extract the necessities of life more efficiently from the environment than their fellows, these individuals may live longer and have more children. The children will carry the new mutation in the genetic codes they have inherited. With a greater ability to adapt to the environment, these new individuals will gradually replace the older population simply by outliving and out-reproducing them.

CULTURAL ADAPTATION

By the time of the emergence of modern human beings, however, the importance of biological adaptation to environmental changes as the key to survival had begun to be overtaken by that of cultural adaptation. Cultural adaptation is the means by which human beings adapt to their environment not through their inherited traits but through learned skills and techniques of survival. Particularly by sharing learned skills with one another -- in other words, through social interaction -- people greatly expanded their capacity for environmental adaptation. Such cooperative activity allows a combination of effort to achieve not only individual survival, but group survival as well.

Cooperative group efforts are generally more efficient than individual efforts in extracting the necessities of life from the environment. For example, a single human being is unlikely to be able to hunt an elephant. A group of people working together, however, may do so with great success. By combining forces, individuals may find that they need not change their behavior to suit the environment. Instead, together they may change the environment to suit themselves.

The ability for cultural adaptation, of course, is at least partly due to the genetic mutations that led to larger and larger brain sizes in both hominids and early human beings. For above all, cultural interaction and exchange require an expanded capacity for memory. It is memory that allows us to store the knowledge we gain from experience. When confronted with new experiences, we may then call up the stored memory of past experiences and compare or contrast the two. We probably all remember the lesson of the hot stove: once burned we remember not to repeat the painful experience. In essence, this is the process of learning - which is dependent upon our capacity for memory.

Equally important, however, is the ability to communicate what we have learned both to other individuals and especially to succeeding generations. Consequently, perhaps the most important development that arose out of such cooperative social interaction was language. Language would establish cultural adaptation as the primary force in human evolution.

The development of language provides a good example of how learned traits and inherited traits interact with each other. Human beings may have learned the importance of cooperation within their groups particularly on the hunting trail. In fact, many scholars believe that language itself probably first developed out of long-distance signals and calls used to coordinate the hunt. Yet even this development was only possible because of genetic changes that had resulted in the development of the human vocal box, a much more flexible tool for making sounds than that of many other species.

Moreover, as early humans became better hunters they also increased the amount of protein, calcium, and other elements essential to the growth of brain cells in their diets. The improved diets stimulated brain development and thus the capacity for greater and greater intelligence. With greater intelligence, humans became even better hunters.

In other words, evolutionary developments often made possible cultural developments—which in turn stimulated further evolutionary developments. In fact, the interactions between biological and cultural means of adaptation have made humanity one of the most flexible species on the planet. This flexibility has been the most important element in both the survival of humanity in the face of all challenges, and in its present ability to transform its own environment in ways unknown to any other species.

Language was a major step forward in cultural terms, for it could soon be used for more than hunting. Personal communications provided opportunities for emotional and intellectual sharing. This must have contributed greatly to the ability of human beings to develop and express their individual sense of identity and to relate it to the larger group identity. Above all, perhaps, language made it possible to share learned experiences among individuals, and from generation to generation.

Cultural adaptation has one tremendous advantage over biological adaptation to a changing environment -- speed. Biological evolution is a long, drawn out process. If there are sudden violent changes in the environment, mutation is far too slow a process to insure individual survival, much less species survival. With cultural adaptation, however, individuals may respond instantly and with much greater flexibility to changes in the environment. This capacity for rapid change guarantees a higher probability that both individuals and the species as a whole will survive and reproduce. The proper beginning of human history might well be seen as the emergence of cultural adaptation as the primary means by which the human species learned to adapt to the environment.

All life depends upon its ability to draw sustenance from its surroundings. For land animals this means air, water and food (including essential elements such as salt), and perhaps shelter. Creatures survive only when they have the physical characteristics and skills needed to obtain these requirements. If the environment changes suddenly, then the characteristics and skills required to continuing extracting the necessary resources may have to change as well.

For example, animals living in a warm climate do not need heavy fur to keep them warm. But if the weather changes and becomes much colder they must adjust to the new temperature or risk freezing to death. Changing climate may also prevent the foods on which they have depended from being able to grow. They must either learn to eat different kinds of foods, which can grow in the new climate, or move away in search of climates where their natural food supply does still grow. The process of making these adjustments to the changing environment in order to survive is called environmental adaptation. What really separated modern humans from their hominid predecessors were the means by which they practiced environmental adaptation.

Early hominids, and perhaps even early human populations, depended for survival primarily on evolution, a process of biological adaptation to their environments. Biological adaptation is the process by which the physical characteristics of a species change over time. Much misunderstood, and still disputed by many scholars, the idea of how species, including humanity, change, was the subject of Charles Darwin's investigations in the 1800s.

As far as scientists can tell now, evolution occurs through sudden changes, called mutations, in the genetic structure of particular individuals. Genes are tiny particles within the physical body, organized in structures called chromosomes, and carried in the reproductive cells of the body. Genes provide the blueprint from which the body itself develops through life. If the genetic structure of a body is somehow changed, then so too will be the information that governs its physical development. When such genetic changes occur, they show up in the form of new physical or mental traits in the next generation. Genetic mutations can be caused by many things. Malnutrition, for example, can cause chromosomal damage. Also, we know that exposure to certain types of radiation, such as extreme sunlight or radioactive materials like uranium and plutonium, as well as exposure to certain man-made and even some naturally occurring chemicals may often cause genetic damage. Even so, we still do not fully understand all the causes of genetic mutation from one generation to the next. Consequently, whether such changes are entirely random or subject to some larger pattern in the universe is a matter of considerable debate.

Although most mutations seem to have negative results, often lessening the chances for survival of those that are affected by them, occasionally the opposite is true. Sometimes, these new, inherited characteristics may give individuals a better chance of adapting to a changing environment than the other members of their species. Being able to extract the necessities of life more efficiently from the environment than their fellows, these individuals may live longer and have more children. The children will carry the new mutation in the genetic codes they have inherited. With a greater ability to adapt to the environment, these new individuals will gradually replace the older population simply by outliving and out-reproducing them.

CULTURAL ADAPTATION

By the time of the emergence of modern human beings, however, the importance of biological adaptation to environmental changes as the key to survival had begun to be overtaken by that of cultural adaptation. Cultural adaptation is the means by which human beings adapt to their environment not through their inherited traits but through learned skills and techniques of survival. Particularly by sharing learned skills with one another -- in other words, through social interaction -- people greatly expanded their capacity for environmental adaptation. Such cooperative activity allows a combination of effort to achieve not only individual survival, but group survival as well.

Cooperative group efforts are generally more efficient than individual efforts in extracting the necessities of life from the environment. For example, a single human being is unlikely to be able to hunt an elephant. A group of people working together, however, may do so with great success. By combining forces, individuals may find that they need not change their behavior to suit the environment. Instead, together they may change the environment to suit themselves.

The ability for cultural adaptation, of course, is at least partly due to the genetic mutations that led to larger and larger brain sizes in both hominids and early human beings. For above all, cultural interaction and exchange require an expanded capacity for memory. It is memory that allows us to store the knowledge we gain from experience. When confronted with new experiences, we may then call up the stored memory of past experiences and compare or contrast the two. We probably all remember the lesson of the hot stove: once burned we remember not to repeat the painful experience. In essence, this is the process of learning - which is dependent upon our capacity for memory.

Equally important, however, is the ability to communicate what we have learned both to other individuals and especially to succeeding generations. Consequently, perhaps the most important development that arose out of such cooperative social interaction was language. Language would establish cultural adaptation as the primary force in human evolution.

The development of language provides a good example of how learned traits and inherited traits interact with each other. Human beings may have learned the importance of cooperation within their groups particularly on the hunting trail. In fact, many scholars believe that language itself probably first developed out of long-distance signals and calls used to coordinate the hunt. Yet even this development was only possible because of genetic changes that had resulted in the development of the human vocal box, a much more flexible tool for making sounds than that of many other species.

Moreover, as early humans became better hunters they also increased the amount of protein, calcium, and other elements essential to the growth of brain cells in their diets. The improved diets stimulated brain development and thus the capacity for greater and greater intelligence. With greater intelligence, humans became even better hunters.

In other words, evolutionary developments often made possible cultural developments—which in turn stimulated further evolutionary developments. In fact, the interactions between biological and cultural means of adaptation have made humanity one of the most flexible species on the planet. This flexibility has been the most important element in both the survival of humanity in the face of all challenges, and in its present ability to transform its own environment in ways unknown to any other species.

Language was a major step forward in cultural terms, for it could soon be used for more than hunting. Personal communications provided opportunities for emotional and intellectual sharing. This must have contributed greatly to the ability of human beings to develop and express their individual sense of identity and to relate it to the larger group identity. Above all, perhaps, language made it possible to share learned experiences among individuals, and from generation to generation.

Cultural adaptation has one tremendous advantage over biological adaptation to a changing environment -- speed. Biological evolution is a long, drawn out process. If there are sudden violent changes in the environment, mutation is far too slow a process to insure individual survival, much less species survival. With cultural adaptation, however, individuals may respond instantly and with much greater flexibility to changes in the environment. This capacity for rapid change guarantees a higher probability that both individuals and the species as a whole will survive and reproduce. The proper beginning of human history might well be seen as the emergence of cultural adaptation as the primary means by which the human species learned to adapt to the environment.

DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN HUMANITY

No one knows exactly when cultural adaptation became more important than biological adaptation in human development, but it certainly took a very long time: from roughly 3.75 million years ago to about 100,000 years ago. Over the intervening span of time several types of creatures appeared and disappeared that seemed to be coming closer to the kind of human beings we are today.

Those that seem to have exhibited behavior characteristic of human beings, but whose physical forms were certainly not those of modern human beings, have been called Homo Habilis, or "skilled man," by many scientists. Campsites from about a million and a half years ago have been found that contain early stone tools, usually in the shape of chipped and sharpened pebbles. Other anthropologists, however, dispute whether all of these creatures were truly human, believing that some may be examples of Australopithecus. By about 1.2 million years ago, a closer relative of modern human beings had appeared called Homo Erectus, or upright man.

Standing a bit over five feet tall, with a sloping forehead and virtually no chin, Homo Erectus had a brain twice the size of all his predecessors - but still only about two-thirds the size of ours. His tools were more complex and highly developed than those of earlier populations. He created and used chopping stones and hand axes. He probably first began to wear clothing, at first loose animal skins for warmth, and later perhaps clothes made of plant materials. Homo Erectus was also probably the first species to discover the use, though not necessarily the control, of fire. Like earlier hominids, Homo Erectus spread beyond the confines of Africa, moving into Europe and even Asia. Fossil remains of Homo Erectus, for example, have been found on the island of Java in Southeast Asia (Java Man), and near modern-day Peking in China (Peking Man).

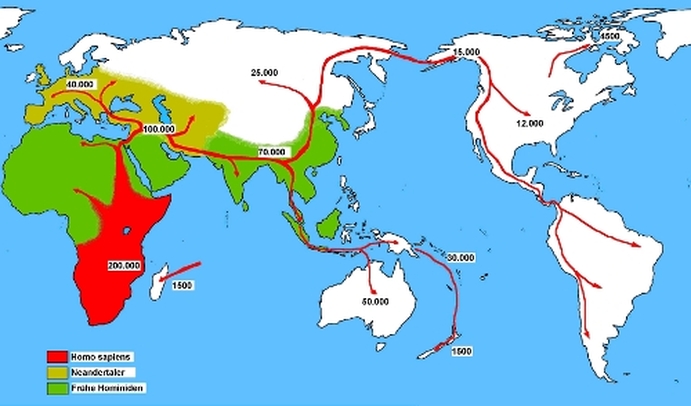

Homo Sapiens. By about 100,000 B.C. the earliest modern human beings, Homo Sapiens, or "thinking man," had appeared in Africa. Over the next sixty thousand years or so they too spread out of Africa and into all the areas previously occupied by the early hominids. Sometime after 40,000 B.C. they even moved into northern Eurasia and Australia. The earliest evidence of Homo Sapiens in North America also dates from about 40,000 B.C., although they apparently did not spread south into Mesoamerica and South America until sometime after about 30,000 B.C.

Taken from: http://archaeology.about.com/od/stoneage/ss/tishkoff_2.htm For a more detailed interactive analysis of human migrations out of Africa based on the most recent genetic evidence see also:http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/journey/

There were apparently two principal strains of Homo Sapiens: Neanderthal, which emerged earlier; and Cro-Magnon, which emerged later. Cro-Magnon represents the first truly modern human population, known as Homo Sapiens Sapiens, or "thinking thinking man." Whether Cro-Magnon competed with the earlier Neanderthal, or even hunted them out of existence, is unclear. Evidence from the Middle East suggests that communities of both sometimes lived near each other, apparently in harmony. Cro-Magnon was clearly the more adaptive, however, for by 30,000 B.C. the Neanderthal record disappears. Yet even as cultural adaptation replaced biological evolution as the primary adaptive technique among human beings, biological development of the species continued. This development can be seen in the minor biological differences that developed among groups of humans after they had spread to various regions of the globe.

WEB RESOURCES: American Museum of Natural History, Hall of Human Origin

No one knows exactly when cultural adaptation became more important than biological adaptation in human development, but it certainly took a very long time: from roughly 3.75 million years ago to about 100,000 years ago. Over the intervening span of time several types of creatures appeared and disappeared that seemed to be coming closer to the kind of human beings we are today.

Those that seem to have exhibited behavior characteristic of human beings, but whose physical forms were certainly not those of modern human beings, have been called Homo Habilis, or "skilled man," by many scientists. Campsites from about a million and a half years ago have been found that contain early stone tools, usually in the shape of chipped and sharpened pebbles. Other anthropologists, however, dispute whether all of these creatures were truly human, believing that some may be examples of Australopithecus. By about 1.2 million years ago, a closer relative of modern human beings had appeared called Homo Erectus, or upright man.

Standing a bit over five feet tall, with a sloping forehead and virtually no chin, Homo Erectus had a brain twice the size of all his predecessors - but still only about two-thirds the size of ours. His tools were more complex and highly developed than those of earlier populations. He created and used chopping stones and hand axes. He probably first began to wear clothing, at first loose animal skins for warmth, and later perhaps clothes made of plant materials. Homo Erectus was also probably the first species to discover the use, though not necessarily the control, of fire. Like earlier hominids, Homo Erectus spread beyond the confines of Africa, moving into Europe and even Asia. Fossil remains of Homo Erectus, for example, have been found on the island of Java in Southeast Asia (Java Man), and near modern-day Peking in China (Peking Man).

Homo Sapiens. By about 100,000 B.C. the earliest modern human beings, Homo Sapiens, or "thinking man," had appeared in Africa. Over the next sixty thousand years or so they too spread out of Africa and into all the areas previously occupied by the early hominids. Sometime after 40,000 B.C. they even moved into northern Eurasia and Australia. The earliest evidence of Homo Sapiens in North America also dates from about 40,000 B.C., although they apparently did not spread south into Mesoamerica and South America until sometime after about 30,000 B.C.

Taken from: http://archaeology.about.com/od/stoneage/ss/tishkoff_2.htm For a more detailed interactive analysis of human migrations out of Africa based on the most recent genetic evidence see also:http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/journey/

There were apparently two principal strains of Homo Sapiens: Neanderthal, which emerged earlier; and Cro-Magnon, which emerged later. Cro-Magnon represents the first truly modern human population, known as Homo Sapiens Sapiens, or "thinking thinking man." Whether Cro-Magnon competed with the earlier Neanderthal, or even hunted them out of existence, is unclear. Evidence from the Middle East suggests that communities of both sometimes lived near each other, apparently in harmony. Cro-Magnon was clearly the more adaptive, however, for by 30,000 B.C. the Neanderthal record disappears. Yet even as cultural adaptation replaced biological evolution as the primary adaptive technique among human beings, biological development of the species continued. This development can be seen in the minor biological differences that developed among groups of humans after they had spread to various regions of the globe.

WEB RESOURCES: American Museum of Natural History, Hall of Human Origin

BEGINNINGS OF 'RACIAL' VARIATIONS Although the actual process by which different types of modern humans emerged is not fully understood, the differences seem to be a result of local adaptation to particular environments. Virtually all modern geneticists, those scientists who specialize in the knowledge of genes and genetic structure, agree that all human beings today, regardless of their different appearance, come from a common ancestry and constitute a single species. The differences, they believe, developed over long periods of time in which groups of humans were separated from others. As each group adapted to its local physical environment, its members developed unique, biologically inherited characteristics that soon distinguished them from other groups. These characteristics have provided the basis for what most people call race. Given the nature of the human experience, however, the story is a bit more complicated than isolated groups developing differently.

For many scientists, the number of races may vary widely, depending upon the different classifications each scholar uses. Some anthropologists, for example, have talked about large groups of populations as continental or geographical races, and smaller population units called local races. In effect, geographical races are made up of several local races that may have slightly different genetic characteristics, but that are more alike to each other than they are to other groups of local races. Even these geographical races, of course, did not yet exist until long after the spread of humanity had separated different groups, and their subsequent history had brought them back into contact in ever new ways.

In fact, there seem to be four basic ways in which different peoples can develop different 'racial' characteristics. Two of them are related aspects of biological adaptation: genetic mutation and natural selection. The other two are due to cultural and social factors:genetic drift, a term that refers to chance genetic changes only within small populations (for example when one male fathers most of the children of a group, most of the descendants of the group will carry his genes); and racial mixing, in which different racial groups begin to intermarry.

It might be argued that all of human history has been a process in which the original human population initially separated as it spread throughout the world into small, isolated groups, and then began to come back together as these scattered groups increased in numbers and gradually mixed together in larger and larger groups. Such mixing, of course, was greatest among groups that lived next to one another, and generally least among populations that lived the farthest from each other. As humanity gradually filled up the planet, however, advances in technology brought more and more populations into contact, resulting in increased levels of 'racial' mixing. Consequently, as we shall see, nomadic warriors from central Asia, conquering settled areas from China to Europe, contributed considerably to 'racial' mixing. So too did the later European migrations around the world, as have all migrations of large groups of people from one area to another.

Perhaps the most difficult questions involving race have come from people using the term in many different ways. It is probably fair to say that most people identify someone else's racial background on the basis of physiognomy, or the visual physical appearance of the person - such as skin color or the shape of body parts like eyes, nose and head. Such a visual method of racial identification, however, is often extremely misleading. For example, from a genetic standpoint it is as wrong to speak of a single Negro race as it is to refer to a single Caucasian race or a single Asian race. The people of Nigeria differ genetically from those of Madagascar or Angola, just as people in Ireland differ genetically from those of Greece and people in Mongolia differ from those in China or Japan. On the other hand, many people associate race with culture, identifying people on the basis of their common history and shared customs. Some have even identified race solely on the basis of language, as for example the "English-speaking race." Still others confuse the idea of race with that of nationality, meaning what country someone comes from, for instance the "German race" or the "Spanish race." Just as confusing is the use of the word race to refer to ethnicity, which is more properly a reference to a combination of genetic and cultural features. Whichever definitions people use, however, in the long history of Humanity the perception of such differences in appearance, in language, in culture, and even national origin have often led to fear, suspicion, hatred and even war, particularly in times of rising insecurity and competition among different groups of people for vital resources.

For many scientists, the number of races may vary widely, depending upon the different classifications each scholar uses. Some anthropologists, for example, have talked about large groups of populations as continental or geographical races, and smaller population units called local races. In effect, geographical races are made up of several local races that may have slightly different genetic characteristics, but that are more alike to each other than they are to other groups of local races. Even these geographical races, of course, did not yet exist until long after the spread of humanity had separated different groups, and their subsequent history had brought them back into contact in ever new ways.

In fact, there seem to be four basic ways in which different peoples can develop different 'racial' characteristics. Two of them are related aspects of biological adaptation: genetic mutation and natural selection. The other two are due to cultural and social factors:genetic drift, a term that refers to chance genetic changes only within small populations (for example when one male fathers most of the children of a group, most of the descendants of the group will carry his genes); and racial mixing, in which different racial groups begin to intermarry.

It might be argued that all of human history has been a process in which the original human population initially separated as it spread throughout the world into small, isolated groups, and then began to come back together as these scattered groups increased in numbers and gradually mixed together in larger and larger groups. Such mixing, of course, was greatest among groups that lived next to one another, and generally least among populations that lived the farthest from each other. As humanity gradually filled up the planet, however, advances in technology brought more and more populations into contact, resulting in increased levels of 'racial' mixing. Consequently, as we shall see, nomadic warriors from central Asia, conquering settled areas from China to Europe, contributed considerably to 'racial' mixing. So too did the later European migrations around the world, as have all migrations of large groups of people from one area to another.

Perhaps the most difficult questions involving race have come from people using the term in many different ways. It is probably fair to say that most people identify someone else's racial background on the basis of physiognomy, or the visual physical appearance of the person - such as skin color or the shape of body parts like eyes, nose and head. Such a visual method of racial identification, however, is often extremely misleading. For example, from a genetic standpoint it is as wrong to speak of a single Negro race as it is to refer to a single Caucasian race or a single Asian race. The people of Nigeria differ genetically from those of Madagascar or Angola, just as people in Ireland differ genetically from those of Greece and people in Mongolia differ from those in China or Japan. On the other hand, many people associate race with culture, identifying people on the basis of their common history and shared customs. Some have even identified race solely on the basis of language, as for example the "English-speaking race." Still others confuse the idea of race with that of nationality, meaning what country someone comes from, for instance the "German race" or the "Spanish race." Just as confusing is the use of the word race to refer to ethnicity, which is more properly a reference to a combination of genetic and cultural features. Whichever definitions people use, however, in the long history of Humanity the perception of such differences in appearance, in language, in culture, and even national origin have often led to fear, suspicion, hatred and even war, particularly in times of rising insecurity and competition among different groups of people for vital resources.