Chapter 2 The First Civilizations

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/Nile-en.svg/526px-Nile-en.svg.png

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/Nile-en.svg/526px-Nile-en.svg.png

Section 2 Civilization in the Nile Valley

While the city-states of Sumer proved the most effective way for Mesopotamians to adapt to their environment, a thousand miles away, in Africa along the river Nile, human beings established a different way of living. The differences between the civilization of Mesopotamia and that of the Nile Valley directly reflected the differences in the two environments.

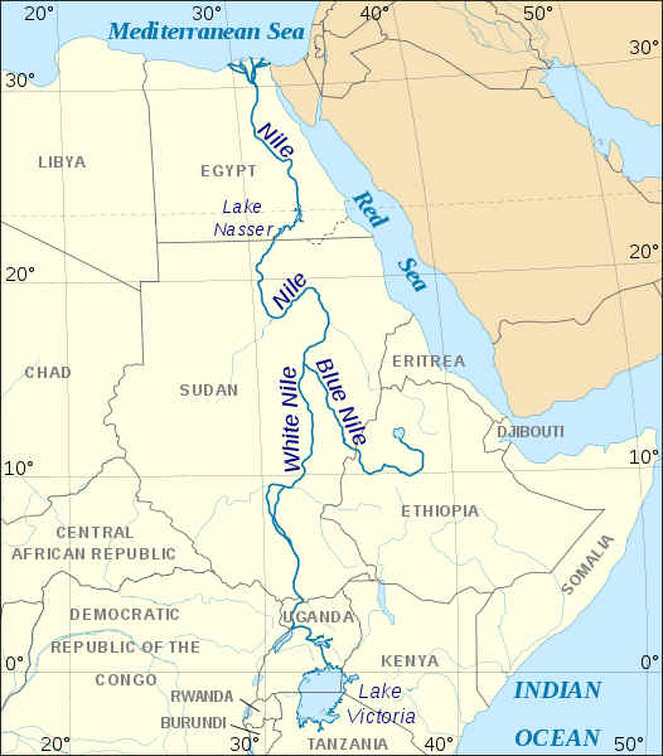

The Nile Valley

The river Nile is the longest river in the world, flowing some 4,160 miles from south to north. It rises from two principal sources: the White Nile rises from the central African lakes of present day Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya. Fed by numerous smaller streams, or tributaries, it makes its way north nearly two thousand miles through the present-day Sudan. At Khartoum, it is joined by the Blue Nile, which springs fresh from Lake Tana in the highlands of Ethiopia some five hundred miles away to the southeast.

From Khartoum the mighty river flows on to the north, over six major cataracts, or falls, winding its way through some of the worst desert on earth, through a valley sometimes broad and sometimes narrow, often lined with steep cliffs that virtually cut off access to the waters from the land. For its last 1600 miles, the Nile flows alone, with no branches or tributaries. As it nears the lowlands along the Mediterranean coast, at modern day Cairo the river begins to spread out in a delta region that is a virtual maze of channels and swamps, filled with great water plants, the famed papyrus, before finally seeping into the Mediterranean Sea.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/Nile-en.svg/526px-Nile-en.svg.png

Unlike the Tigris and Euphrates, which were dependent upon the often unpredictable weather patterns of the eastern Mediterranean and the Turkish highlands, the Nile's flood depended upon the annual melting of year-round snows in the high mountains of north-central and northeast Africa, and heavy annual rains in the upper valleys of the Blue Nile in Ethiopia. Both the rains and the snowmelt occur with little variation from year to year, although periodically shifting weather patterns could delay the rains or even lessen their volume. This meant that the annual floods were almost always predictable, with only occasional periods during which they might be delayed or lessened in volume.

Although the channels of the Delta may shift somewhat, with no severe storms upriver to affect the river's flow the annual flooding even of this lower region is still more predictable and less destructive than that of Sumer. Upriver, where the Nile flows relatively swift and untroubled within its banks, the flood is also generally predictable and steady - again very different from the Tigris and the Euphrates. Like the Mesopotamian rivers, however, the Nile too brought rich deposits of silt down from the volcanic highlands, renewing the fertility of the river valley's soil every year. The annual flood of the Nile thus made its valley one of the richest agricultural areas in the world.

While the city-states of Sumer proved the most effective way for Mesopotamians to adapt to their environment, a thousand miles away, in Africa along the river Nile, human beings established a different way of living. The differences between the civilization of Mesopotamia and that of the Nile Valley directly reflected the differences in the two environments.

The Nile Valley

The river Nile is the longest river in the world, flowing some 4,160 miles from south to north. It rises from two principal sources: the White Nile rises from the central African lakes of present day Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya. Fed by numerous smaller streams, or tributaries, it makes its way north nearly two thousand miles through the present-day Sudan. At Khartoum, it is joined by the Blue Nile, which springs fresh from Lake Tana in the highlands of Ethiopia some five hundred miles away to the southeast.

From Khartoum the mighty river flows on to the north, over six major cataracts, or falls, winding its way through some of the worst desert on earth, through a valley sometimes broad and sometimes narrow, often lined with steep cliffs that virtually cut off access to the waters from the land. For its last 1600 miles, the Nile flows alone, with no branches or tributaries. As it nears the lowlands along the Mediterranean coast, at modern day Cairo the river begins to spread out in a delta region that is a virtual maze of channels and swamps, filled with great water plants, the famed papyrus, before finally seeping into the Mediterranean Sea.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/Nile-en.svg/526px-Nile-en.svg.png

Unlike the Tigris and Euphrates, which were dependent upon the often unpredictable weather patterns of the eastern Mediterranean and the Turkish highlands, the Nile's flood depended upon the annual melting of year-round snows in the high mountains of north-central and northeast Africa, and heavy annual rains in the upper valleys of the Blue Nile in Ethiopia. Both the rains and the snowmelt occur with little variation from year to year, although periodically shifting weather patterns could delay the rains or even lessen their volume. This meant that the annual floods were almost always predictable, with only occasional periods during which they might be delayed or lessened in volume.

Although the channels of the Delta may shift somewhat, with no severe storms upriver to affect the river's flow the annual flooding even of this lower region is still more predictable and less destructive than that of Sumer. Upriver, where the Nile flows relatively swift and untroubled within its banks, the flood is also generally predictable and steady - again very different from the Tigris and the Euphrates. Like the Mesopotamian rivers, however, the Nile too brought rich deposits of silt down from the volcanic highlands, renewing the fertility of the river valley's soil every year. The annual flood of the Nile thus made its valley one of the richest agricultural areas in the world.

In addition to the river, the Nile Valley has several other distinguishing characteristics that affected the style of civilization that developed there. Although in the late Neolithic period the surrounding territory was relatively well watered by rain, by about 3000 B.C., when civilization emerged in the river valley, climate changes had begun to make the surrounding lands virtual deserts. These deserts seem to have served for a time as a barrier to outside invasion of the river valley by nomadic peoples. The river too, although navigable for considerable portions of its length, was marked by a series of cataracts, or rapids, which made access from the far south difficult. Moreover, with little or no rain, especially in the southern part of the valley, the single most important natural feature dominating the landscape, apart from the Nile itself, was the glaring, hot African sun. As might be expected, the Egyptian view of the world was forged between the hammer and anvil of the mighty river Nile and the Lord of Heaven, the Sun.

The Nile River and delta surrounded by desert as seen from space. http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5b/Nile_Valley.jpg/333px-Nile_Valley.jpg

Origins of Egyptian CivilizationThe basis of civilization in the Nile Valley, as in ancient Mesopotamia, lay in Neolithic farming villages that the people of the region had gradually established between about 10,000 and 3000 B.C. Why these relatively autonomous communities began to come together remains something of a mystery, but it is reasonable to suggest that climatic changes, particularly desertification, or drying out, of the Sahara, which gradually confined human existence to the river valley itself, was the primary cause. As the surrounding region became drier and drier, people naturally moved closer and closer to the water supply on which their food production depended. More people living closely together in turn fostered the need for greater organization, in short, civilization.

Within this basic scenario, recent archeological findings suggest that at least three separate types of culture contributed to the emergence of civilization along the Nile. The upper reaches of the river produced highly organized and prosperous farming communities, which were gradually brought together under the rule of local leaders in a kind of plantation system. Eventually a single leader united all of them into a kingdom, known as Upper Egypt.

This unifying process in turn was probably carried out under the influence of surrounding pastoralists, who lived in the arid, but still habitable plains away from the river itself, both to the east and the west. These pastoralists declined in importance as their grazing lands dried up; eventually they were either absorbed or ridiculed as 'barbarians' by the inhabitants of the river valley.

Meanwhile, in the delta region to the north, an even more sophisticated culture was emerging, in which long-distance trade and commerce, particularly with the east, matched the importance of agriculture. The delta too was eventually unified, if rather loosely, under a single leader, but perhaps because of its primary interest in trade and commerce the delta kingdom seems to have been less warlike than its southern neighbor. The dangers of such a peaceful attitude became clear around 3100 B.C. when the king of Upper Egypt, traditionally named Menes, conquered the delta and proclaimed himself Pharaoh, Lord of the Two Lands.

INTERNET RESOURCE: The Ancient Egypt Site

The Nile River and delta surrounded by desert as seen from space. http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5b/Nile_Valley.jpg/333px-Nile_Valley.jpg

Origins of Egyptian CivilizationThe basis of civilization in the Nile Valley, as in ancient Mesopotamia, lay in Neolithic farming villages that the people of the region had gradually established between about 10,000 and 3000 B.C. Why these relatively autonomous communities began to come together remains something of a mystery, but it is reasonable to suggest that climatic changes, particularly desertification, or drying out, of the Sahara, which gradually confined human existence to the river valley itself, was the primary cause. As the surrounding region became drier and drier, people naturally moved closer and closer to the water supply on which their food production depended. More people living closely together in turn fostered the need for greater organization, in short, civilization.

Within this basic scenario, recent archeological findings suggest that at least three separate types of culture contributed to the emergence of civilization along the Nile. The upper reaches of the river produced highly organized and prosperous farming communities, which were gradually brought together under the rule of local leaders in a kind of plantation system. Eventually a single leader united all of them into a kingdom, known as Upper Egypt.

This unifying process in turn was probably carried out under the influence of surrounding pastoralists, who lived in the arid, but still habitable plains away from the river itself, both to the east and the west. These pastoralists declined in importance as their grazing lands dried up; eventually they were either absorbed or ridiculed as 'barbarians' by the inhabitants of the river valley.

Meanwhile, in the delta region to the north, an even more sophisticated culture was emerging, in which long-distance trade and commerce, particularly with the east, matched the importance of agriculture. The delta too was eventually unified, if rather loosely, under a single leader, but perhaps because of its primary interest in trade and commerce the delta kingdom seems to have been less warlike than its southern neighbor. The dangers of such a peaceful attitude became clear around 3100 B.C. when the king of Upper Egypt, traditionally named Menes, conquered the delta and proclaimed himself Pharaoh, Lord of the Two Lands.

INTERNET RESOURCE: The Ancient Egypt Site

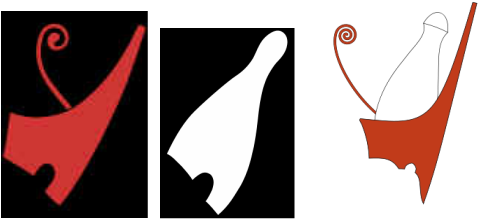

The Red Crown of Lower Egypt (left), the White Crown of Upper Egypt (center) and the Double Crown of Pharaoh, Lord of the Two Lands (right) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pschent

The Red Crown of Lower Egypt (left), the White Crown of Upper Egypt (center) and the Double Crown of Pharaoh, Lord of the Two Lands (right) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pschent

Patterns of History: The Dynastic Cycle of the Pharaohs

Traditionally, civilization in the Nile valley is said to begin with the unification of upper and lower Egypt under the first Pharaoh, Menes, in 3100 B.C. The history of the civilization is usually divided into three periods in which the valley was unified under the authority of a series of some thirty ruling families, or dynasties (hence the term Dynastic Period), separated by two Intermediate periods, when the central power disintegrated. The unification of the two kingdoms was visibly portrayed in painting and statuary by showing pharaohs wearing the so-called double crown, which combined the traditional red crown of Lower Egypt, called the Deshret, with the Hedjet, the white crown of Upper Egypt. The combined "double crown" was known as Pschent.

The first dynastic period occurred in two stages: the Archaic Period of the first two dynasties, when the patterns for Pharaonic rule were being firmly established; and the Old Kingdom. Altogether, six dynasties ruled during this era of about 800 years, in relative peace and prosperity. Gradually, however, as the dynasties placed more and more emphasis on expensive state projects, such as building the pyramids, the people of Egypt began to be overtaxed and impoverished. As disillusionment with the Pharaohs set in, local provincial governors began to gain more and more power for themselves.

Eventually, squabbling among these local nobles resulted in the downfall of the Pharaoh's central authority. Beginning in about 2160 B.C., a period of civil war led to the collapse of central authority. For nearly 150 years the Nile valley experienced political disunity, as local nobles fought with one another, perhaps over the right to call themselves Pharaoh. This period is known as the First Intermediate Period.

In about 2040 B.C., the rise of the 11th dynasty signaled the reunification of Egypt and the beginning of the Middle Kingdom, which saw the accomplishments of the Old Kingdom expanded and spread to benefit not just the Pharaohs, but the general population as well. Learning the lessons of the end of the Old Kingdom, under the 12th dynasty in particular, pharaohs began to pursue policies that centered less on their own roles as god-kings and more on improving the lives of their subjects.

By about 1782 B.C., however, dynastic rule of the pharaohs weakened once again as nobles and priests struggled among themselves for more power. Then, beginning in the 1760s, foreign marauders began to attack Egypt. These attacks culminated in the first full-scale foreign invasion of the valley. The fall of the 12th dynasty to these invaders in 1650 B.C. marked the beginning of two centuries of foreign domination and internal turmoil. This Second Intermediate Period was finally brought to an end in 1570 B.C., when the founder of the 18th dynasty, Ahmose, reunited all of Egypt and threw out the last of the foreign invaders.

Ahmose's success marked the last dynastic period, sometimes called the Late Kingdom, but usually referred to more accurately as the period of the Empire. The Empire in turn lasted until the conquest of Egypt by more foreign invaders, first from the west, then the south, and finally from the east, when Egypt was incorporated into the Assyrian empire in 670 B.C. Although Assyrian rule only lasted about 18 years, followed by a brief but brilliant renaissance of indigenous Egyptian culture, the final blow came at the hands of the Persians, who conquered the valley in 525. After the Persian conquest, Egypt never really recovered its independence from foreign rule until the 20th century A.D.

Traditionally, civilization in the Nile valley is said to begin with the unification of upper and lower Egypt under the first Pharaoh, Menes, in 3100 B.C. The history of the civilization is usually divided into three periods in which the valley was unified under the authority of a series of some thirty ruling families, or dynasties (hence the term Dynastic Period), separated by two Intermediate periods, when the central power disintegrated. The unification of the two kingdoms was visibly portrayed in painting and statuary by showing pharaohs wearing the so-called double crown, which combined the traditional red crown of Lower Egypt, called the Deshret, with the Hedjet, the white crown of Upper Egypt. The combined "double crown" was known as Pschent.

The first dynastic period occurred in two stages: the Archaic Period of the first two dynasties, when the patterns for Pharaonic rule were being firmly established; and the Old Kingdom. Altogether, six dynasties ruled during this era of about 800 years, in relative peace and prosperity. Gradually, however, as the dynasties placed more and more emphasis on expensive state projects, such as building the pyramids, the people of Egypt began to be overtaxed and impoverished. As disillusionment with the Pharaohs set in, local provincial governors began to gain more and more power for themselves.

Eventually, squabbling among these local nobles resulted in the downfall of the Pharaoh's central authority. Beginning in about 2160 B.C., a period of civil war led to the collapse of central authority. For nearly 150 years the Nile valley experienced political disunity, as local nobles fought with one another, perhaps over the right to call themselves Pharaoh. This period is known as the First Intermediate Period.

In about 2040 B.C., the rise of the 11th dynasty signaled the reunification of Egypt and the beginning of the Middle Kingdom, which saw the accomplishments of the Old Kingdom expanded and spread to benefit not just the Pharaohs, but the general population as well. Learning the lessons of the end of the Old Kingdom, under the 12th dynasty in particular, pharaohs began to pursue policies that centered less on their own roles as god-kings and more on improving the lives of their subjects.

By about 1782 B.C., however, dynastic rule of the pharaohs weakened once again as nobles and priests struggled among themselves for more power. Then, beginning in the 1760s, foreign marauders began to attack Egypt. These attacks culminated in the first full-scale foreign invasion of the valley. The fall of the 12th dynasty to these invaders in 1650 B.C. marked the beginning of two centuries of foreign domination and internal turmoil. This Second Intermediate Period was finally brought to an end in 1570 B.C., when the founder of the 18th dynasty, Ahmose, reunited all of Egypt and threw out the last of the foreign invaders.

Ahmose's success marked the last dynastic period, sometimes called the Late Kingdom, but usually referred to more accurately as the period of the Empire. The Empire in turn lasted until the conquest of Egypt by more foreign invaders, first from the west, then the south, and finally from the east, when Egypt was incorporated into the Assyrian empire in 670 B.C. Although Assyrian rule only lasted about 18 years, followed by a brief but brilliant renaissance of indigenous Egyptian culture, the final blow came at the hands of the Persians, who conquered the valley in 525. After the Persian conquest, Egypt never really recovered its independence from foreign rule until the 20th century A.D.

The Structure and Character of Egyptian CivilizationAlthough scholars argue over why the inhabitants of the Nile valley moved from the stage of Neolithic farming villages to the emergence of civilization, the best evidence still points to a combination of environmental factors. The Nile, like the Mesopotamian rivers, required considerable work to make it sustain farming. In Upper Egypt, where the river flowed through straight banks, canals had to be dug to bring the water to the fields. During the flood, farmers had to build levies, or embankments of earth, to channel the waters into fields or containment areas where they could be stored for future use.

In the delta too, the flood had to be controlled, lest it destroy the fields on which people depended for survival. All this activity required the same kind of organizational skills that the ancient Sumerians had worked out. These skills had emerged in Egypt, however, long before the beginning of what we would now call civilization; consequently, there must have been more to Egypt's move to civilization than simply the development of irrigation agriculture.

Modern irrigation canal in the Nile delta. http://girlsoloinarabia.typepad.com/photos/egypt/nile_delta2.jpg

Surplus food production, so important in all civilizations, had produced thriving communities along the Nile well before the dynastic period. They probably began to get bigger because of the changing climate. As the surrounding lands got drier more and more people moved close to the river. It was probably this climatic change that caused the development of even greater levels of organization, eventually leading to the creation of kingdoms and finally the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt.

The archeological record tells us that for all the regularity of the Nile, and the fertility of the soil, the Nile Valley experienced periods of drought, when normal levels of food production dropped dramatically. The biblical story of Joseph, who became a chief adviser to Pharaoh because of his prediction that seven fat years would be followed by seven lean years, and that Egypt would be saved by storing grain during the fat years, reflects a central pattern of Egyptian history. Flooding too could destroy crops in years when the annual Nile flood was much higher than usual. Such events were not as frequent in Egypt as in Mesopotamia but they were sufficiently threatening to human existence that Egyptians began to store grain during seasons of plenty to be used in times of famine.

Large-scale food storage, and distribution of such surpluses when the time came, required an even greater level of organization than simply tapping into the Nile. As local leaders began to create such surplus storage facilities, they naturally became both social and political leaders on whom other members of the community depended for survival in hard times. Out of this pattern, the real authority of the Pharaohs gradually emerged, first at the local level, then through regional kingdoms, and finally throughout the entire Nile Valley.

Probably because of this complete dependence on agriculture, civilization in Egypt, as in Mesopotamia, was also seen as an extension of the underlying religious order of the universe. The old Neolithic view of Nature as fundamentally alive also prevailed here. The forces of Nature were immortal spirits, gods and goddesses, who insured the continuity of the world in which people lived. Those specialists who understood them, the priests, naturally became the leaders of Egyptian society.

In the delta too, the flood had to be controlled, lest it destroy the fields on which people depended for survival. All this activity required the same kind of organizational skills that the ancient Sumerians had worked out. These skills had emerged in Egypt, however, long before the beginning of what we would now call civilization; consequently, there must have been more to Egypt's move to civilization than simply the development of irrigation agriculture.

Modern irrigation canal in the Nile delta. http://girlsoloinarabia.typepad.com/photos/egypt/nile_delta2.jpg

Surplus food production, so important in all civilizations, had produced thriving communities along the Nile well before the dynastic period. They probably began to get bigger because of the changing climate. As the surrounding lands got drier more and more people moved close to the river. It was probably this climatic change that caused the development of even greater levels of organization, eventually leading to the creation of kingdoms and finally the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt.

The archeological record tells us that for all the regularity of the Nile, and the fertility of the soil, the Nile Valley experienced periods of drought, when normal levels of food production dropped dramatically. The biblical story of Joseph, who became a chief adviser to Pharaoh because of his prediction that seven fat years would be followed by seven lean years, and that Egypt would be saved by storing grain during the fat years, reflects a central pattern of Egyptian history. Flooding too could destroy crops in years when the annual Nile flood was much higher than usual. Such events were not as frequent in Egypt as in Mesopotamia but they were sufficiently threatening to human existence that Egyptians began to store grain during seasons of plenty to be used in times of famine.

Large-scale food storage, and distribution of such surpluses when the time came, required an even greater level of organization than simply tapping into the Nile. As local leaders began to create such surplus storage facilities, they naturally became both social and political leaders on whom other members of the community depended for survival in hard times. Out of this pattern, the real authority of the Pharaohs gradually emerged, first at the local level, then through regional kingdoms, and finally throughout the entire Nile Valley.

Probably because of this complete dependence on agriculture, civilization in Egypt, as in Mesopotamia, was also seen as an extension of the underlying religious order of the universe. The old Neolithic view of Nature as fundamentally alive also prevailed here. The forces of Nature were immortal spirits, gods and goddesses, who insured the continuity of the world in which people lived. Those specialists who understood them, the priests, naturally became the leaders of Egyptian society.

An Egyptian Worldview. Here, however, the pattern that emerged in Egypt took a different path from that of Mesopotamia. After unification of the Nile valley, and the drying up of the surrounding territory, in Egypt there was little threat from outside invaders. Nor was there much competition among villages for water resources, due to the constant abundance of the Nile. Consequently, the Egyptian conception of what the natural world was like varied dramatically from that of Mesopotamia. Egyptians saw life from the vantage point of relative security. The measured flow of the Nile marked the slow, generally peaceful hours of their lives, from generation to generation. Optimism rather than the Mesopotamian pessimism colored all aspects of Egyptian life.

The essentially secure character of life in Egypt also meant that the nature of cities developed differently from those of Mesopotamia. Egyptian cities were originally less cities in the modern sense of the word than ritual centers. Even after the unification of upper and lower Egypt, the vast majority of Egyptians continued to live in their agricultural villages.

Cities developed primarily as centers for grain storage and the religious rituals that surrounded food production - or life itself as the Egyptians saw it. They were occupied permanently by Pharaoh, his court, and the priests and their attendants, but only visited by the rest of Egyptian society for religious occasions, or to obtain food supplies when necessary. Consequently, they had no significant defensive walls and the most important buildings were the great temple complexes and royal palaces, which were often connected with granaries. There were, of course, private residences for courtiers, and over the years these became increasingly important. During the Middle Kingdom, too, a rising middle echelon of Egyptian society, composed of artisans, merchants, and other non-agrarian specialists, made private dwellings and civic architecture more prominent, but in general the cities of Pharaonic Egypt continued to reflect the complete identification of temporal, or worldly power, with spiritual authority. Egyptians simply did not distinguish between the two, as did the Mesopotamians.

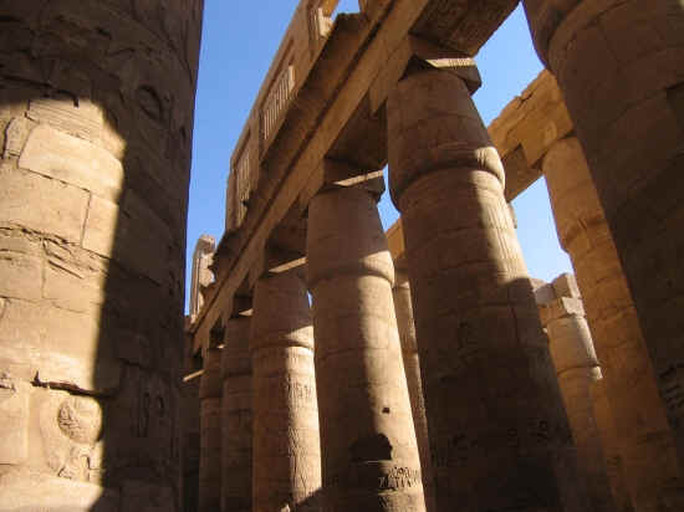

Ancient Thebes, the principal capital of Egypt from about 2060-1685 BC, and again from 1580-1353 BC, and for the final time from 1332-1085 BC, lay on both sides of the Nile about 420 miles south of modern Cairo. At its height, Thebes covered some six square miles, mostly on the east side of the river. The necropolis, or 'city of the dead' lay on the west side of the river and was primarily comprised of the mortuary temples of the pharaohs, as well as the homes of all those who tended them - priests, craftsmen, workers and guards.

At the heart of the city on the east bank were two great temple complexes dedicated to the sun god Amun-Re, one at Luxor (photo above http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luxor) which lay to the south, and especially the great complex of Karnak (photo below), situated two miles further north and encompassing some two square miles in its own right. A magnificent ceremonial road, lined on both sides by statues of sphinxes and rams, ran the two miles between the two temples of Amun-Re. In addition, the Karnak complex also contained shrines and small temples to various other gods; and two smaller self-contained temple complexes lay nearby, one dedicated to the war god Mont, and the other to the goddess Mut, the wife of Amun. Unfortunately, the palaces, houses and gardens that would have been occupied by pharaohs and their courtiers and administrators have not been preserved.

The essentially secure character of life in Egypt also meant that the nature of cities developed differently from those of Mesopotamia. Egyptian cities were originally less cities in the modern sense of the word than ritual centers. Even after the unification of upper and lower Egypt, the vast majority of Egyptians continued to live in their agricultural villages.

Cities developed primarily as centers for grain storage and the religious rituals that surrounded food production - or life itself as the Egyptians saw it. They were occupied permanently by Pharaoh, his court, and the priests and their attendants, but only visited by the rest of Egyptian society for religious occasions, or to obtain food supplies when necessary. Consequently, they had no significant defensive walls and the most important buildings were the great temple complexes and royal palaces, which were often connected with granaries. There were, of course, private residences for courtiers, and over the years these became increasingly important. During the Middle Kingdom, too, a rising middle echelon of Egyptian society, composed of artisans, merchants, and other non-agrarian specialists, made private dwellings and civic architecture more prominent, but in general the cities of Pharaonic Egypt continued to reflect the complete identification of temporal, or worldly power, with spiritual authority. Egyptians simply did not distinguish between the two, as did the Mesopotamians.

Ancient Thebes, the principal capital of Egypt from about 2060-1685 BC, and again from 1580-1353 BC, and for the final time from 1332-1085 BC, lay on both sides of the Nile about 420 miles south of modern Cairo. At its height, Thebes covered some six square miles, mostly on the east side of the river. The necropolis, or 'city of the dead' lay on the west side of the river and was primarily comprised of the mortuary temples of the pharaohs, as well as the homes of all those who tended them - priests, craftsmen, workers and guards.

At the heart of the city on the east bank were two great temple complexes dedicated to the sun god Amun-Re, one at Luxor (photo above http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luxor) which lay to the south, and especially the great complex of Karnak (photo below), situated two miles further north and encompassing some two square miles in its own right. A magnificent ceremonial road, lined on both sides by statues of sphinxes and rams, ran the two miles between the two temples of Amun-Re. In addition, the Karnak complex also contained shrines and small temples to various other gods; and two smaller self-contained temple complexes lay nearby, one dedicated to the war god Mont, and the other to the goddess Mut, the wife of Amun. Unfortunately, the palaces, houses and gardens that would have been occupied by pharaohs and their courtiers and administrators have not been preserved.

Hypostyle hall of the magnificent temple of Amun-Re at Karnak, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karnak

Hypostyle hall of the magnificent temple of Amun-Re at Karnak, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karnak

Church and State met in the person of the Pharaoh, who stood at the center of ancient Egyptian society for most of its history. Although Pharaoh, like the ancient Sumerian kings, was both king and chief priest, these two roles were combined differently in Egypt than they had been in Sumerian experience. While it is at least arguable that kingship in both civilizations developed out of the early need for military leadership, in Egypt, once the valley had been united under a single ruler, the religious and spiritual aspect of kingship overshadowed the military aspect. Pharaoh was not only king and chief priest in Egypt, but a living god in flesh.

During the Archaic period of the first two dynasties, Pharaoh's role was far more dependent upon his ability to provide food during times of natural hardship than upon his role as a general. Consequently, his function became connected with the rhythms of agriculture as practiced in the Nile Valley. Like all other aspects of the early Nile valley civilization, these rhythms reflected the Egyptians' spiritual conception of the nature of the universe and humanity's role in it.

Egyptian Religion. In Egypt, as in Mesopotamia, the Neolithic conviction that the natural world was alive continued to dominate people's conception of reality. Consequently, here too life was seen primarily in religious terms, with the physical world as simply an extension of the spiritual world. The nature of the spiritual world, however, was very different for ancient Egyptians than it was for ancient Mesopotamians. Where the gods and goddesses of the Land Between the Rivers were as fickle and violent as the natural forces in which they showed themselves, in Egypt the gods reflected the relatively gentle and predictable nature of life along the Nile.

Even before the unification of Egypt, the river itself was a primary deity in the Neolithic farming villages, since it was a principle source of life. The ancient “Hymn to the Nile” expressed Egyptians’ gratitude for the river’s life-giving force:

Hail to thee, O Nile, that issues from the earth and comes to keep Egypt alive! …When the Nile floods offering is made to thee, oxen are sacrificed to thee…birds are fattened for thee, lions are hunted for thee in the desert, fire is provided for thee. And offering is made to every other god, as is done for the Nile…. So it is ‘Verdant art thou!’ So it is ‘Verdant art thou!’ So it is ‘O Nile, verdant art thou, who makest man and cattle to live!

The rhythms of life that followed the Nile's constant flow were naturally seen as the rhythms governing the entire universe. Life for the Egyptians was a never-ending cycle of birth, life, death, and regeneration or rebirth, a pattern that was all around them in the annual flood of the great river, and the constant regeneration of Egypt's fertility. The constancy of the Nile was like the heartbeat of ancient Egypt, an eternal pulse that never failed.

Equal in importance to the Nile, however, was that great power that constantly overlooked human affairs, the sun. Traveling on its daily journey across the sky, the sun was just as constant, indeed, even more constant, than the Nile. Given its overarching height, Neolithic Egyptians could easily imagine the sun as a guardian spirit, infused with light that protected them from the dangers of the night. Like the river too, the sun was eventually understood as a giver of life to both the earth and human beings, and so was worshiped in Egypt as a good and vital force governing people's lives.

Before the unification of Egypt under Menes, the local farming communities worshiped these two great powers, along with other lesser spirits, under a variety of names. The lesser deities generally represented forces or natural features that were particularly important to the individual villages. With the unification of the Nile Valley, however, the gods too were unified.

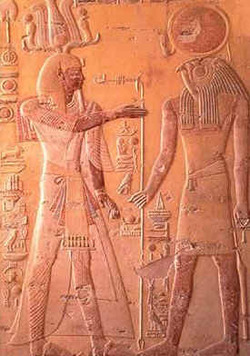

Since the sun was clearly the most obvious guardian power, looking down from on high, local guardian deities were generally fused into the single great god of the sun, Re (or Amon-Re as he was called during the Middle Kingdom, after the chief god of the city of Thebes, whose dynasty had reunited Egypt). Similarly, all local gods or goddesses associated with the regenerative powers of the Nile and the vegetation that depended on it (and that so clearly mimicked its own rising and falling pattern in the cycle of life, death, and rebirth) were gathered into the great god Osiris. During the dynastic era, both great gods of Egypt were brought together in a single earthly representative immediately visible and approachable by human beings, Pharaoh.

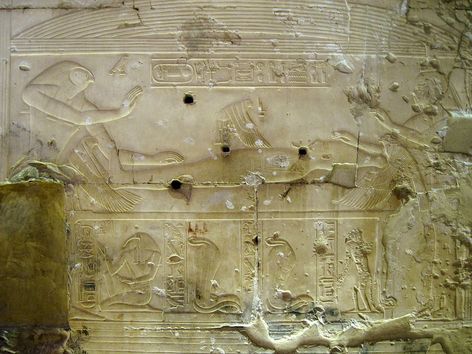

Re-Horakhty ("Ra is Horus of the Horizon") on the right above faces with Osiris on the left. Note the solar disk and the falcon Horus in the image of Re - both are representations of the sun.http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/re.htm

With little need for military protection after the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, Pharaoh's role was not so much to maintain external security as to perpetuate the constant cycles of Nature and the order of the universe. Reflecting this function, his life from beginning to end became one long religious ritual - re-enacting, and thereby sustaining, the rhythms of the universe. Even in death, Pharaoh was merely demonstrating one part of the natural cycle of birth, life, death, and re-birth that Egyptians saw all around them in the seasons of the Nile. His very body thus became a symbol of the perpetuation of the natural order. Consequently, its preservation was important to all Egyptians. It was but a short step from this to seeing Pharaoh as a living god.

In fact, Pharaoh came to be seen as an earthly embodiment of more than one god, depending upon which phase of his life he happened to be in. In the Old Kingdom, by the time of the Fourth Dynasty he was primarily associated with the sun god, Re. Although the sun was seen as a bringer of life, Egyptians realized that it could also be a bringer of death, particularly when separated from the life-giving waters of the Nile. Egyptians resolved this apparent duality in the sun's nature by seeing Re not only as a guardian, but also as the god of truth, justice, and righteousness, responsible for upholding the moral order of the universe, and bringing life or death according to the merits of the individual.

As the earthly representation of Re, therefore, Pharaoh too became responsible for upholding the moral order on earth. His word thus became law, and his was the final judgment on earth for all human beings. In addition to being Re, however, especially during the Middle Kingdom Pharaoh also came to be seen as a representative of the god Osiris, around whom the Egyptians developed an elaborate myth to explain the cycle of life, death and re-birth.

Equal in importance to the Nile, however, was that great power that constantly overlooked human affairs, the sun. Traveling on its daily journey across the sky, the sun was just as constant, indeed, even more constant, than the Nile. Given its overarching height, Neolithic Egyptians could easily imagine the sun as a guardian spirit, infused with light that protected them from the dangers of the night. Like the river too, the sun was eventually understood as a giver of life to both the earth and human beings, and so was worshiped in Egypt as a good and vital force governing people's lives.

Before the unification of Egypt under Menes, the local farming communities worshiped these two great powers, along with other lesser spirits, under a variety of names. The lesser deities generally represented forces or natural features that were particularly important to the individual villages. With the unification of the Nile Valley, however, the gods too were unified.

Since the sun was clearly the most obvious guardian power, looking down from on high, local guardian deities were generally fused into the single great god of the sun, Re (or Amon-Re as he was called during the Middle Kingdom, after the chief god of the city of Thebes, whose dynasty had reunited Egypt). Similarly, all local gods or goddesses associated with the regenerative powers of the Nile and the vegetation that depended on it (and that so clearly mimicked its own rising and falling pattern in the cycle of life, death, and rebirth) were gathered into the great god Osiris. During the dynastic era, both great gods of Egypt were brought together in a single earthly representative immediately visible and approachable by human beings, Pharaoh.

Re-Horakhty ("Ra is Horus of the Horizon") on the right above faces with Osiris on the left. Note the solar disk and the falcon Horus in the image of Re - both are representations of the sun.http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/re.htm

With little need for military protection after the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, Pharaoh's role was not so much to maintain external security as to perpetuate the constant cycles of Nature and the order of the universe. Reflecting this function, his life from beginning to end became one long religious ritual - re-enacting, and thereby sustaining, the rhythms of the universe. Even in death, Pharaoh was merely demonstrating one part of the natural cycle of birth, life, death, and re-birth that Egyptians saw all around them in the seasons of the Nile. His very body thus became a symbol of the perpetuation of the natural order. Consequently, its preservation was important to all Egyptians. It was but a short step from this to seeing Pharaoh as a living god.

In fact, Pharaoh came to be seen as an earthly embodiment of more than one god, depending upon which phase of his life he happened to be in. In the Old Kingdom, by the time of the Fourth Dynasty he was primarily associated with the sun god, Re. Although the sun was seen as a bringer of life, Egyptians realized that it could also be a bringer of death, particularly when separated from the life-giving waters of the Nile. Egyptians resolved this apparent duality in the sun's nature by seeing Re not only as a guardian, but also as the god of truth, justice, and righteousness, responsible for upholding the moral order of the universe, and bringing life or death according to the merits of the individual.

As the earthly representation of Re, therefore, Pharaoh too became responsible for upholding the moral order on earth. His word thus became law, and his was the final judgment on earth for all human beings. In addition to being Re, however, especially during the Middle Kingdom Pharaoh also came to be seen as a representative of the god Osiris, around whom the Egyptians developed an elaborate myth to explain the cycle of life, death and re-birth.

According to tradition, Osiris had been a great king who had taught his people the arts of civilization, and particularly the secrets of agriculture. This benevolent ruler, however, was murdered by his evil brother, Set, who cut the body into pieces and scattered them throughout the land. Osiris's wife, who was also his sister, Isis, thereupon journeyed throughout Egypt, gathering up all the pieces. Putting them all together again, she miraculously restored Osiris to life, at least long enough to make her pregnant. Osiris then went down into the underworld to become the judge of the dead. After this second death, Isis gave birth to Osiris's son, Horus, who eventually grew up and avenged his father by killing his wicked uncle Set.

Although clearly a nature myth, in which the death and resurrection of Osiris represented the fall of the Nile in Autumn and its flood in Spring, as well as the flowering, death, and re-flowering of plant life throughout the year, the Osiris myth came to have an even deeper meaning for most Egyptians. In their tombs, Pharaohs were often depicted as having been Horus during their lifetimes, only to become Osiris in death. This depiction as Osiris was especially important, for it was seen as a promise of immortality. Indeed, as both Horus and Osiris, Pharaoh was in a sense his own father and his own son in an everlasting cycle of regeneration. Moreover, as Horus, who killed the wicked Set, he embodied the triumph of good over evil.

The development of the Osiris myth reflected not only an increasingly moral element in Egyptian religion, but also a promise of eternal life that soon extended beyond Pharaoh to all Egyptians. During the Middle Kingdom especially, the Osiris myth came to be applied not simply to Pharaoh, although his participation in the myth was carried out on behalf of the nation as a whole, but also to every individual who adhered to the moral order represented by the gods, Pharaoh and the priests of Egypt. Where in Mesopotamia Gilgamesh's quest for immortality was doomed to failure, in Egypt it was increasingly taken for granted. The whole character of Egyptian society and culture reflected this religious view of the world, a view that in turn reflected the environment from which it developed. So important was the Egyptian concern with the search for immortality that it provided perhaps the major focus for the development of Egyptian religion, art and culture.

As with earlier human conceptions of reality, Egyptians believed that the physical and spiritual worlds, the seen and the unseen, were somehow linked together. Thus the human being was thought to consist of several parts, of which the physical body was the connecting link. The spirit body, or ka, as well as the mind body, or ba, continued to use the physical body as a kind of house, even after it had died. Consequently, the physical body's preservation in the earthly realm of existence was seen as essential for insuring the continued existence of these non-physical aspects of the person in the spiritual realms.

The after-life itself seems to have been thought of in remarkably physical terms. For those who achieved it, eternity consisted of a pleasant existence in a land of gardens and vineyards, surrounded by material pleasures. Those who did not achieve eternity, on the other hand, were utterly destroyed. This gave rise to an almost obsessive concern in Egypt with mummification of the body and the building of tombs that would last forever. In fact, the Egyptians called their tombs 'houses of eternity.' In these tombs they not only left stores of food and other essential items, for the use of the spirit on its journey through the underworld, but also specimens of virtually every important item the living had used in their lifetimes.

Eventually, the Egyptians seem to have concluded that replicas could replace real objects, since they would be used not by the physical body but by its spiritual counterparts. In other words, it was the idea of the offerings that was important. At the same time, however, human memory also played a part in insuring immortality, for the Egyptians believed that so long as one's name continued to be spoken, existence in the after-life was assured. This belief sometimes led vengeful pharaohs to attempt to obliterate their enemies even after death by having their names and all references to them removed from the monuments and temples of Egypt. Needless to say, such practices have often made the archeologists' work more difficult.

During the Early Kingdom, immortality seems to have been a prerogative of Pharaoh alone. As the kingdom became more prosperous, however, the concept seems to have been extended further: first to the nobility, provincial governors and important priests, and then, especially during the Middle Kingdom, to all Egyptians. As the promise of eternal life was extended, so too were the ethical requirements for attaining it. The Osiris myth, for example, with all its implications for an ethical system of behavior in the struggle between good (Horus) and evil (Set), only appeared towards the end of the Old Kingdom. By the time of the Middle Kingdom, the elements of the Osiris myth had been combined with those of the solar worship of Amon-Re to create a truly ethical religion.

Although clearly a nature myth, in which the death and resurrection of Osiris represented the fall of the Nile in Autumn and its flood in Spring, as well as the flowering, death, and re-flowering of plant life throughout the year, the Osiris myth came to have an even deeper meaning for most Egyptians. In their tombs, Pharaohs were often depicted as having been Horus during their lifetimes, only to become Osiris in death. This depiction as Osiris was especially important, for it was seen as a promise of immortality. Indeed, as both Horus and Osiris, Pharaoh was in a sense his own father and his own son in an everlasting cycle of regeneration. Moreover, as Horus, who killed the wicked Set, he embodied the triumph of good over evil.

The development of the Osiris myth reflected not only an increasingly moral element in Egyptian religion, but also a promise of eternal life that soon extended beyond Pharaoh to all Egyptians. During the Middle Kingdom especially, the Osiris myth came to be applied not simply to Pharaoh, although his participation in the myth was carried out on behalf of the nation as a whole, but also to every individual who adhered to the moral order represented by the gods, Pharaoh and the priests of Egypt. Where in Mesopotamia Gilgamesh's quest for immortality was doomed to failure, in Egypt it was increasingly taken for granted. The whole character of Egyptian society and culture reflected this religious view of the world, a view that in turn reflected the environment from which it developed. So important was the Egyptian concern with the search for immortality that it provided perhaps the major focus for the development of Egyptian religion, art and culture.

As with earlier human conceptions of reality, Egyptians believed that the physical and spiritual worlds, the seen and the unseen, were somehow linked together. Thus the human being was thought to consist of several parts, of which the physical body was the connecting link. The spirit body, or ka, as well as the mind body, or ba, continued to use the physical body as a kind of house, even after it had died. Consequently, the physical body's preservation in the earthly realm of existence was seen as essential for insuring the continued existence of these non-physical aspects of the person in the spiritual realms.

The after-life itself seems to have been thought of in remarkably physical terms. For those who achieved it, eternity consisted of a pleasant existence in a land of gardens and vineyards, surrounded by material pleasures. Those who did not achieve eternity, on the other hand, were utterly destroyed. This gave rise to an almost obsessive concern in Egypt with mummification of the body and the building of tombs that would last forever. In fact, the Egyptians called their tombs 'houses of eternity.' In these tombs they not only left stores of food and other essential items, for the use of the spirit on its journey through the underworld, but also specimens of virtually every important item the living had used in their lifetimes.

Eventually, the Egyptians seem to have concluded that replicas could replace real objects, since they would be used not by the physical body but by its spiritual counterparts. In other words, it was the idea of the offerings that was important. At the same time, however, human memory also played a part in insuring immortality, for the Egyptians believed that so long as one's name continued to be spoken, existence in the after-life was assured. This belief sometimes led vengeful pharaohs to attempt to obliterate their enemies even after death by having their names and all references to them removed from the monuments and temples of Egypt. Needless to say, such practices have often made the archeologists' work more difficult.

During the Early Kingdom, immortality seems to have been a prerogative of Pharaoh alone. As the kingdom became more prosperous, however, the concept seems to have been extended further: first to the nobility, provincial governors and important priests, and then, especially during the Middle Kingdom, to all Egyptians. As the promise of eternal life was extended, so too were the ethical requirements for attaining it. The Osiris myth, for example, with all its implications for an ethical system of behavior in the struggle between good (Horus) and evil (Set), only appeared towards the end of the Old Kingdom. By the time of the Middle Kingdom, the elements of the Osiris myth had been combined with those of the solar worship of Amon-Re to create a truly ethical religion.

At the heart of the Egyptian religious worldview was the concept of ma'at, the cosmic harmony and sacred order of the universe. Ma'at represented not only the fundamental balance and equilibrium of the natural world but also that of the human world. It bound everything and everyone in mutual obligation to uphold order instead of chaos. People were enjoined to be truthful, honest, and just in their dealings with others; to respect traditions and to show proper devotion to the gods. If they lived according to ma'at, they might achieve immortality - if they passed the judgement of the gods.

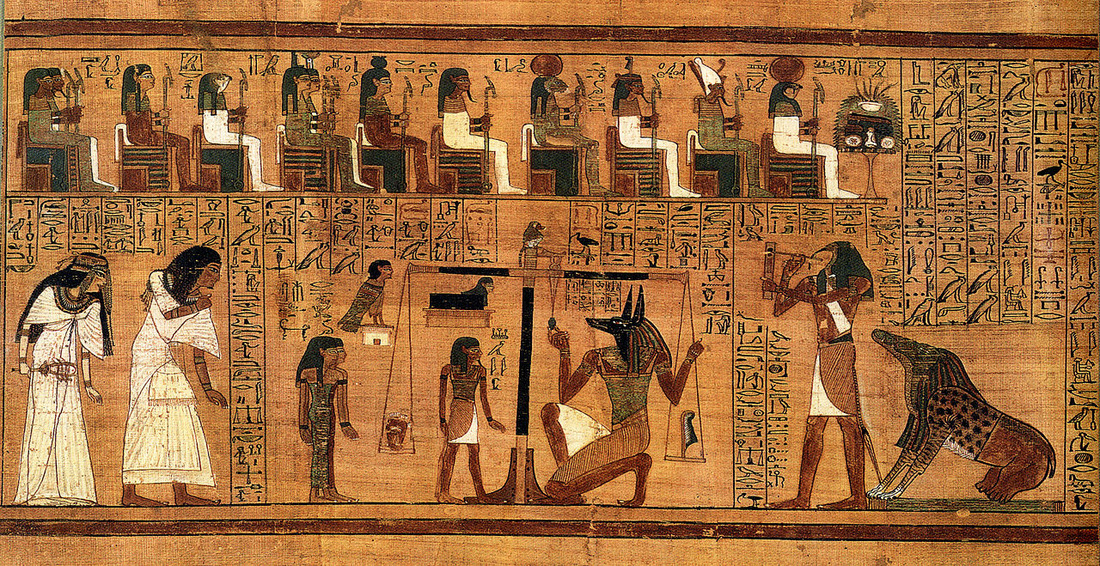

After death, the soul would travel through the underworld to appear before Osiris, the God of the Dead, for judgment. Here, before the giver of personal immortality, the deeds of the living human, recorded in the heart, would be weighed in the scales against the feather of ma'at, or truth. If the scales balanced, then the soul achieved immortality; if not, then the unfortunate person was immediately dispatched into the jaws of a ferocious monster and utterly consumed. Acting justly and with goodness had become the key to everlasting life; it would remain so until outside invasion and a rising sense of insecurity destroyed the Egyptians' natural optimism, fostering in its place a growing cynicism in life and fear of death.

After death, the soul would travel through the underworld to appear before Osiris, the God of the Dead, for judgment. Here, before the giver of personal immortality, the deeds of the living human, recorded in the heart, would be weighed in the scales against the feather of ma'at, or truth. If the scales balanced, then the soul achieved immortality; if not, then the unfortunate person was immediately dispatched into the jaws of a ferocious monster and utterly consumed. Acting justly and with goodness had become the key to everlasting life; it would remain so until outside invasion and a rising sense of insecurity destroyed the Egyptians' natural optimism, fostering in its place a growing cynicism in life and fear of death.

"The Weighing of the Heart from the Book of the Dead of Ani. At left, Ani and his wife Tutu enter the assemblage of gods. At center, Anubis weighs Ani's heart against the feather of Maat, observed by the goddesses Renenutet and Meshkenet, the god Shay, and Ani's own ba. At right, the monster Ammut, who will devour Ani's soul if he is unworthy, awaits the verdict, while the god Thoth prepares to record it. At top are gods acting as judges: Hu and Sia, Hathor, Horus, Isis and Nephthys, Nut, Geb, Tefnut, Shu, Atum, and Ra-Horakhty." http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maat#mediaviewer/File:BD_Weighing_of_the_Heart.jpg

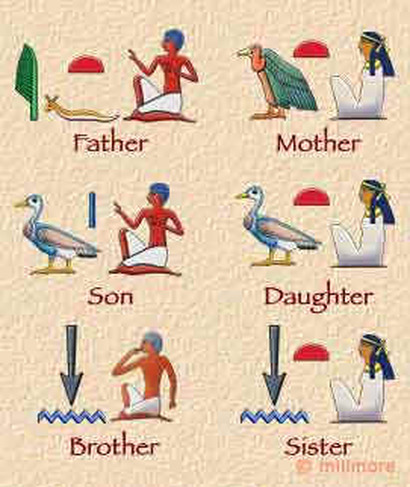

Examples of hieroglyphic writing. http://www.discoveringegypt.com/pics/famley.jpg

Examples of hieroglyphic writing. http://www.discoveringegypt.com/pics/famley.jpg

Egyptian Society and Culture

As it had in Sumer, the reliance of civilization in the Nile Valley upon irrigation agriculture demanded an improvement in the level of knowledge and technology from the old Neolithic farming communities. Perhaps the most significant development was that of writing. Like the Sumerians, the Egyptians had to keep track of the grain in their storage bins and warehouses, as well as who owed what to the central authorities of the local regions.

Even before the unification of the Valley under the Pharaohs, a pictographic form of writing, called hieroglyphic (from a Greek word meaning 'sacred carving'), had begun to be developed for this purpose of record keeping. As in Mesopotamia, hieroglyphic writing began as a pictographic system, in which particular signs were used for concrete objects. Gradually, some of the characters came to be used to suggest abstract ideas, while others were used in combination to represent syllables of the spoken language. Eventually, towards the end of the Old Kingdom, some 24 symbols were added to the hieroglyphic system, each representing the sound of a single consonant. Thus, after a development of several hundred years, Egyptian hieroglyphics came to consist of three different kinds of symbols, pictographic, syllabic and alphabetic, all of which were used in combination for the next several thousand years.

In Egypt too, the development of hieroglyphics produced an increasingly specialized group of priests, an elite who spent much of their time mastering the art of reading and writing the new characters. The use of writing soon went far beyond simple recording, especially after the unification of the Valley and the development of the Pharaonic order in Egypt. Consequently, education focused not only on reading and writing skills, but also all those other specialized tasks we usually associate with advanced civilizations.

Egyptian Sciences. Like the Mesopotamians, Egyptians concentrated on knowledge and skills that were of direct practical value in their lives: astronomy, mathematics, and medicine. The ancient Egyptians had little use for speculative knowledge. They studied astronomy primarily to help them predict the timing of the Nile floods. Mathematics, which they confined largely to arithmetic and geometry, was important for building purposes. Medicine, of course, was not only important for keeping people alive and healthy, but also for learning how to preserve the body in death, through the process of mummification.

In addition to these key areas of knowledge, however, Egyptians also learned important physical skills. They developed considerable expertise, for example, in metallurgy. They invented the sundial, and they learned the process of making glass. Not least, they invented the making of a kind of paper from the papyrus plants of the Nile. Perhaps the most famous of their accomplishments, however, was their development of architectural skills – as testified by the still awe-inspiring pyramids.

As it had in Sumer, the reliance of civilization in the Nile Valley upon irrigation agriculture demanded an improvement in the level of knowledge and technology from the old Neolithic farming communities. Perhaps the most significant development was that of writing. Like the Sumerians, the Egyptians had to keep track of the grain in their storage bins and warehouses, as well as who owed what to the central authorities of the local regions.

Even before the unification of the Valley under the Pharaohs, a pictographic form of writing, called hieroglyphic (from a Greek word meaning 'sacred carving'), had begun to be developed for this purpose of record keeping. As in Mesopotamia, hieroglyphic writing began as a pictographic system, in which particular signs were used for concrete objects. Gradually, some of the characters came to be used to suggest abstract ideas, while others were used in combination to represent syllables of the spoken language. Eventually, towards the end of the Old Kingdom, some 24 symbols were added to the hieroglyphic system, each representing the sound of a single consonant. Thus, after a development of several hundred years, Egyptian hieroglyphics came to consist of three different kinds of symbols, pictographic, syllabic and alphabetic, all of which were used in combination for the next several thousand years.

In Egypt too, the development of hieroglyphics produced an increasingly specialized group of priests, an elite who spent much of their time mastering the art of reading and writing the new characters. The use of writing soon went far beyond simple recording, especially after the unification of the Valley and the development of the Pharaonic order in Egypt. Consequently, education focused not only on reading and writing skills, but also all those other specialized tasks we usually associate with advanced civilizations.

Egyptian Sciences. Like the Mesopotamians, Egyptians concentrated on knowledge and skills that were of direct practical value in their lives: astronomy, mathematics, and medicine. The ancient Egyptians had little use for speculative knowledge. They studied astronomy primarily to help them predict the timing of the Nile floods. Mathematics, which they confined largely to arithmetic and geometry, was important for building purposes. Medicine, of course, was not only important for keeping people alive and healthy, but also for learning how to preserve the body in death, through the process of mummification.

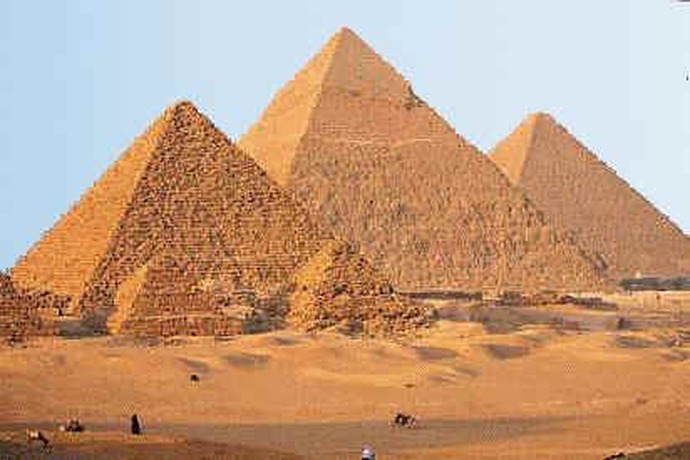

In addition to these key areas of knowledge, however, Egyptians also learned important physical skills. They developed considerable expertise, for example, in metallurgy. They invented the sundial, and they learned the process of making glass. Not least, they invented the making of a kind of paper from the papyrus plants of the Nile. Perhaps the most famous of their accomplishments, however, was their development of architectural skills – as testified by the still awe-inspiring pyramids.

A mastaba (left), http://www.ancient-egypt-online.com/images/mastabas.jpg; the step pyramid of Djoser (right), http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3e/Pyramid_of_Djoser_2010.jpg/300px-Pyramid_of_Djoser_2010.jpg

A mastaba (left), http://www.ancient-egypt-online.com/images/mastabas.jpg; the step pyramid of Djoser (right), http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3e/Pyramid_of_Djoser_2010.jpg/300px-Pyramid_of_Djoser_2010.jpg

Architecture. Among the most famous ancient Egyptian monuments are the Great Sphinx and the pyramids. Believed by most scholars to be about 4,500 years old, the huge stone figure of the Sphinx, with the body of a lion and the head of a man, may represent the ancient Egyptian sun god, though no one really knows for sure. The pyramids were almost certainly built as tombs for the pharaohs.

The earliest pyramids developed out of a simpler tomb architectural form called a mastaba, a square or rectangular single story structure. During the Old Kingdom, Egyptian architects began to experiment with piling several mastabas one on top of the other, each one successively smaller. The result can most clearly be seen in the remains of the famous step pyramid of King Djoser, designed by the most renowned Egyptian architect, Imhotep, during the Old Kingdom period.

The earliest pyramids developed out of a simpler tomb architectural form called a mastaba, a square or rectangular single story structure. During the Old Kingdom, Egyptian architects began to experiment with piling several mastabas one on top of the other, each one successively smaller. The result can most clearly be seen in the remains of the famous step pyramid of King Djoser, designed by the most renowned Egyptian architect, Imhotep, during the Old Kingdom period.

The Great Pyramid complex on the Giza plateau. http://www.pagefarm.net/wiki/index.php?title=Image:Pyramid3.jpg

The Great Pyramid complex on the Giza plateau. http://www.pagefarm.net/wiki/index.php?title=Image:Pyramid3.jpg

Imhotep was not only a brilliant architect but also became known as a great healer and a master of the art of writing. An inscription on the pyramid calls him "Chancellor of the king of Lower Egypt, . . . hereditary prince, controller of the palace, great seer, . . . builder and sculptor." So great was his reputation that long after his death he came to be worshipped as a god in his own right. Eventually, architects like Imhotep developed the early, cruder forms into highly sophisticated and mathematically perfect pyramids.

Most of the eighty or so pyramids that still stand cluster in groups along the west bank of the Nile. The best known are at Giza, including the Great Pyramid, built about 2600 B.C. as the tomb of the pharaoh Cheops. Egyptian architects and engineers proved themselves to be among the most skilful in the ancient world. Orienting their pyramids on perfect north/south axes, with a precision difficult to match even today, they apparently built upward sloping ramps, along which workers pushed or pulled enormous stones weighing many tons, course by course into the sky. Once the basic stones were in place, casing stones of marble or granite were laid over them to make the sides perfectly smooth. The final touch was probably to polish their entire surfaces until they gleamed in the sunlight, visible for miles around – a mute but inescapably magnificent testimony to the immortality of the pharaohs who occupied them through the long ages of eternity.

Education. Over time Egypt developed a bureaucracy, a complex governmental structure in which civil servants carried out many specialized tasks. The Egyptian bureaucracy required many scribes to keep records. The scribes were all men, and they enjoyed positions of honor. Although women were not permitted to be scribes, some women among the upper classes were probably literate. During the Old Kingdom, boys were usually trained by their fathers to read and write. After the Old Kingdom fell, however, many of the skills needed to run a state were lost. As literacy rates fell, the old system of fathers teaching sons was no longer adequate. By the rise of the Middle Kingdom, actual schools had begun to appear.

Farming and trade. While the magnificence of the pharaohs and their courtiers tend to draw most of our attention, ordinary Egyptians, the vast majority of the population, continued to center their lives on food production – especially farming along the Nile. Farmland in Egypt was divided into large estates. Peasants did most of the farming, using crude hoes or wooden plows. They kept only part of their crops, however, paying the rest in rent or taxes for pharaoh. The most important grain crops were wheat and barley. Farmers also grew flax, a fibrous plant that could be spun and woven into linen.

So rich was the soil, because of the annual flooding and deposits of silt, that ancient Egypt almost always produced more food than its people required. Such surpluses not only made possible the development of civilization within the Valley itself, but also contributed to the growth of long-distance trade as Egyptian merchants exchanged Egypt’s products for items from beyond their borders.

Living along the Nile, Egyptians had learned early on to use the river as a highway, building boats out of the papyrus reeds that grew in such abundance along its banks. While the current could be counted on to carry them downstream, they soon learned to use large triangular sails to take advantage of prevailing northerly winds to carry them back upstream, against the current. Having thus mastered sailing on the Nile, it was not long before Egyptians also built seagoing ships that sailed the Mediterranean, Red, and Aegean Seas, as well as along the African coast. Egyptian merchants also traveled overland, joining caravans east into Asia and south into Africa. Through the richness of her soil, her ability to trade its products for the wealth of neighboring lands, and the security provided by her natural geography, Egypt became the wealthiest and most peaceful of the ancient world’s civilizations.

INTERNET RESOURCE: Discovering Ancient Egypt

Most of the eighty or so pyramids that still stand cluster in groups along the west bank of the Nile. The best known are at Giza, including the Great Pyramid, built about 2600 B.C. as the tomb of the pharaoh Cheops. Egyptian architects and engineers proved themselves to be among the most skilful in the ancient world. Orienting their pyramids on perfect north/south axes, with a precision difficult to match even today, they apparently built upward sloping ramps, along which workers pushed or pulled enormous stones weighing many tons, course by course into the sky. Once the basic stones were in place, casing stones of marble or granite were laid over them to make the sides perfectly smooth. The final touch was probably to polish their entire surfaces until they gleamed in the sunlight, visible for miles around – a mute but inescapably magnificent testimony to the immortality of the pharaohs who occupied them through the long ages of eternity.

Education. Over time Egypt developed a bureaucracy, a complex governmental structure in which civil servants carried out many specialized tasks. The Egyptian bureaucracy required many scribes to keep records. The scribes were all men, and they enjoyed positions of honor. Although women were not permitted to be scribes, some women among the upper classes were probably literate. During the Old Kingdom, boys were usually trained by their fathers to read and write. After the Old Kingdom fell, however, many of the skills needed to run a state were lost. As literacy rates fell, the old system of fathers teaching sons was no longer adequate. By the rise of the Middle Kingdom, actual schools had begun to appear.

Farming and trade. While the magnificence of the pharaohs and their courtiers tend to draw most of our attention, ordinary Egyptians, the vast majority of the population, continued to center their lives on food production – especially farming along the Nile. Farmland in Egypt was divided into large estates. Peasants did most of the farming, using crude hoes or wooden plows. They kept only part of their crops, however, paying the rest in rent or taxes for pharaoh. The most important grain crops were wheat and barley. Farmers also grew flax, a fibrous plant that could be spun and woven into linen.

So rich was the soil, because of the annual flooding and deposits of silt, that ancient Egypt almost always produced more food than its people required. Such surpluses not only made possible the development of civilization within the Valley itself, but also contributed to the growth of long-distance trade as Egyptian merchants exchanged Egypt’s products for items from beyond their borders.

Living along the Nile, Egyptians had learned early on to use the river as a highway, building boats out of the papyrus reeds that grew in such abundance along its banks. While the current could be counted on to carry them downstream, they soon learned to use large triangular sails to take advantage of prevailing northerly winds to carry them back upstream, against the current. Having thus mastered sailing on the Nile, it was not long before Egyptians also built seagoing ships that sailed the Mediterranean, Red, and Aegean Seas, as well as along the African coast. Egyptian merchants also traveled overland, joining caravans east into Asia and south into Africa. Through the richness of her soil, her ability to trade its products for the wealth of neighboring lands, and the security provided by her natural geography, Egypt became the wealthiest and most peaceful of the ancient world’s civilizations.

INTERNET RESOURCE: Discovering Ancient Egypt