Image from http://www.in2greece.com/english/maps/map_of_Ancient_Greece.jpg

Image from http://www.in2greece.com/english/maps/map_of_Ancient_Greece.jpg

Chapter 4

The Persian and Greek World

Section 2 The City-States of Greece

WEB RESOURCE: Ancient Greece

While the Persians were laying the foundations for their vast empire, further west another branch of the Indo-European-speaking peoples developed a very different style of civilization along the rocky coast and islands of Greece and the Aegean Sea. In the eight century B.C. the isolation of the Greek world began to break down. For historians of the ancient Mediterranean civilizations, this century marks the end of the "Dark Age" and the beginning of the "Archaic Age" in Greek history (c. 750-478 B.C.). Greek civilization developed around hundreds of independent city-states, which became the focal points for Greek identity.

The “Archaic Age” of Greece

As the isolation of the so-called “Dark Age” began to end during the 700s, Greeks once again looked out on a larger world. At the core of the emerging Greek worldview was the conception of the polis, the primary form of Greek political and social organization. Although today we generally translate polis as “city-state,” for the Greeks it meant much more than the English word can convey. The poleis (plural of polis) had emerged during the violent and insecure days of the Dark Age when many Greek tribes had banded together in small groups, each centered on a hill or some other strong point that could provide protection and be easily defended. As the Greeks struggled to survive, they forged a whole new sense of identity around their poleis. For the ancient Greeks the concept of the polis involved three interlocking ideas: geographical territory; community; and political and economic independence from any other group.

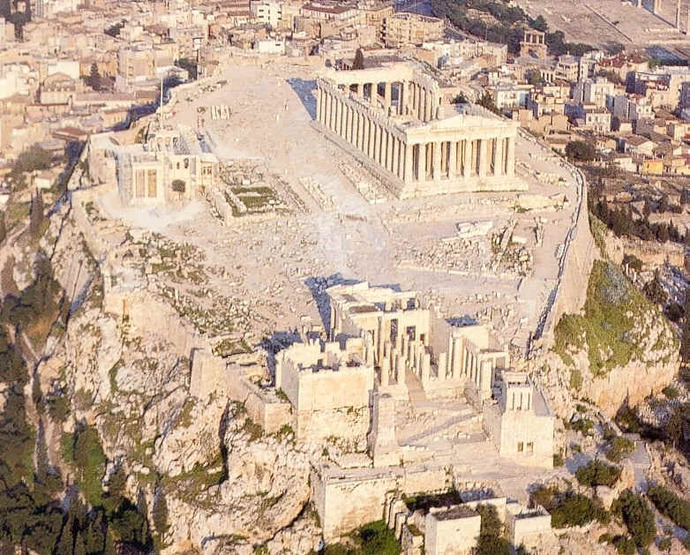

Ruins of the acropolis of Athens, from http://www.artlex.com/ArtLex/a/images/acropolis_aerial.lg.jpg

Ruins of the acropolis of Athens, from http://www.artlex.com/ArtLex/a/images/acropolis_aerial.lg.jpg

Independent city-states. Physically, the polis consisted of a city built around a defensible fortification called an acropolis, and the surrounding countryside from which the city drew most of its food. The average polis was relatively small, covering between 30 to 500 square miles. The relatively small size was important since ideally all citizens of the polis knew one another. Most poleis seem to have had less than a thousand adult male citizens, with perhaps ten times as many non-citizen inhabitants. Perhaps the most famous polis, Athens, was an exception. Athens covered over a thousand square miles, and had a commensurately larger population than most of the other poleis. In 431 B.C., for example, Athens had about forty thousand adult male citizens and a total population of some two hundred thousand people.

Whatever its size, however, the polis became the heart and soul of the Greek identity and fostered intense loyalty among its inhabitants. A later Greek philosopher, for example, went so far as to define the term “human being” as “an animal whose nature is to live in a polis.” An individual without a polis was indeed a lost soul for the ancient Greeks; the polis itself, on the other hand, was an absolutely independent and self-sufficient entity.

Perhaps the most important underlying principle of the polis was that a citizen was not an entirely autonomous individual, but rather belonged to the state. The Greeks made little or no distinction between public and private sectors of life. The polis had no professional bureaucracy, for example, nor a professional army, nor professional politicians – it relied on all of its citizens to fulfill all of these duties as required, in turn. Moreover, this concept of the polis allowed for no sense of individualism, as we know the term today.

All Greeks were members of an interlocking set of larger and larger groups – their family, clan, brotherhood, tribe and polis, in that order. These groups provided both material and above all psychological security for people in the face of a dangerous and insecure world – no one stood alone. Consequently, in a polis any citizen could begin a legal case in a matter of public concern. Even more, any citizen who avoided participating in political life risked losing his citizenship altogether. As one Athenian statesman put it:

"Here each individual is interested not only in his own affairs but in the affairs of the state as well: even those who are mostly occupied with their own business are extremely well informed on general politics…. We do not say that a man who takes no interest in politics is a man who minds his own business; we say that he has no business here at all."

Whatever its size, however, the polis became the heart and soul of the Greek identity and fostered intense loyalty among its inhabitants. A later Greek philosopher, for example, went so far as to define the term “human being” as “an animal whose nature is to live in a polis.” An individual without a polis was indeed a lost soul for the ancient Greeks; the polis itself, on the other hand, was an absolutely independent and self-sufficient entity.

Perhaps the most important underlying principle of the polis was that a citizen was not an entirely autonomous individual, but rather belonged to the state. The Greeks made little or no distinction between public and private sectors of life. The polis had no professional bureaucracy, for example, nor a professional army, nor professional politicians – it relied on all of its citizens to fulfill all of these duties as required, in turn. Moreover, this concept of the polis allowed for no sense of individualism, as we know the term today.

All Greeks were members of an interlocking set of larger and larger groups – their family, clan, brotherhood, tribe and polis, in that order. These groups provided both material and above all psychological security for people in the face of a dangerous and insecure world – no one stood alone. Consequently, in a polis any citizen could begin a legal case in a matter of public concern. Even more, any citizen who avoided participating in political life risked losing his citizenship altogether. As one Athenian statesman put it:

"Here each individual is interested not only in his own affairs but in the affairs of the state as well: even those who are mostly occupied with their own business are extremely well informed on general politics…. We do not say that a man who takes no interest in politics is a man who minds his own business; we say that he has no business here at all."

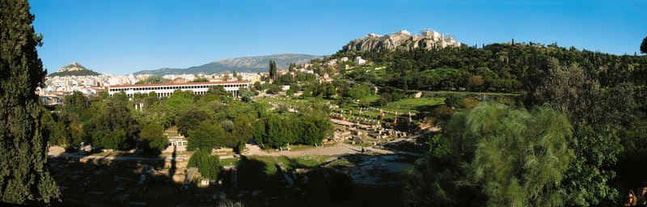

Remains of the agora of Athens, looking across to the hill of the acropolis, from

http://www.agathe.gr/image?id=Agora%3AImage%3A2008.18.0256;w=800;h=600

Remains of the agora of Athens, looking across to the hill of the acropolis, from

http://www.agathe.gr/image?id=Agora%3AImage%3A2008.18.0256;w=800;h=600

Life in the Polis

Within the walls of the polis, life centered on the agora, or market place. Here farmers from the surrounding countryside could sell their produce and buy in turn the goods made by artisans within the city or brought from beyond the polis by long-distance traders and merchants. Socially, three separate groups inhabited the polis – citizens, adult men with political rights and responsibilities; non-citizens, free people without political rights or responsibilities, such as women and children and resident foreigners; and slaves, who only counted as someone’s property.

The Greek polis was an entirely male-dominated society. Women were supposed to stay in the home taking care of household responsibilities; men often saw them as a burden. According to one ancient text, even the poorest families always found means to keep sons, while even the richest families often exposed unwanted daughters on hillsides outside the cities to die. (Infanticide of unwanted children, either due to sex or physical deformity, was common among the Greeks as well as some other ancient peoples.) Part of the problem in this patriarchal Indo-European society, particularly when times were hard, was that daughters could be a serious economic liability – they had to be provided with a dowry either of goods or money before they could be married. As bad as their lot might be, however, if they survived childhood free women were still better off than the lowest group in Greek society – the slaves.

Although some of our earliest sources seem to suggest that slavery was not always practiced among the Greeks, eventually slavery became a fundamental institution in Greek society. Prisoners of war were usually enslaved and even Greeks themselves could be sold (or sell themselves or their children) into slavery in payment of debts. In some cases, entire city populations were enslaved by conquerors. Slaves not only worked in homes and in the fields, but in any other capacity their masters might require. The worst life for a slave was in the mines, where conditions were so harsh that few survived for very long. Although customs varied from city to city, in general slaves had no rights against their masters whatsoever.

Within the walls of the polis, life centered on the agora, or market place. Here farmers from the surrounding countryside could sell their produce and buy in turn the goods made by artisans within the city or brought from beyond the polis by long-distance traders and merchants. Socially, three separate groups inhabited the polis – citizens, adult men with political rights and responsibilities; non-citizens, free people without political rights or responsibilities, such as women and children and resident foreigners; and slaves, who only counted as someone’s property.

The Greek polis was an entirely male-dominated society. Women were supposed to stay in the home taking care of household responsibilities; men often saw them as a burden. According to one ancient text, even the poorest families always found means to keep sons, while even the richest families often exposed unwanted daughters on hillsides outside the cities to die. (Infanticide of unwanted children, either due to sex or physical deformity, was common among the Greeks as well as some other ancient peoples.) Part of the problem in this patriarchal Indo-European society, particularly when times were hard, was that daughters could be a serious economic liability – they had to be provided with a dowry either of goods or money before they could be married. As bad as their lot might be, however, if they survived childhood free women were still better off than the lowest group in Greek society – the slaves.

Although some of our earliest sources seem to suggest that slavery was not always practiced among the Greeks, eventually slavery became a fundamental institution in Greek society. Prisoners of war were usually enslaved and even Greeks themselves could be sold (or sell themselves or their children) into slavery in payment of debts. In some cases, entire city populations were enslaved by conquerors. Slaves not only worked in homes and in the fields, but in any other capacity their masters might require. The worst life for a slave was in the mines, where conditions were so harsh that few survived for very long. Although customs varied from city to city, in general slaves had no rights against their masters whatsoever.

From http://www.utexas.edu/courses/greeksahoy!/greek_colonies_550.jpg

From http://www.utexas.edu/courses/greeksahoy!/greek_colonies_550.jpg

Greek Colonization

The development of the poleis soon led to a falling Insecurity Index in Greece. By the 8th century B.C. mainland Greeks once again experienced rising levels of security and prosperity. The results were enormous – as people felt more secure, they began to have more children. At the same time, greater security and prosperity also made it possible for more children and young adults to actually survive into adulthood. Such prosperity, however, contained the seeds of its own destruction. The rapid and dramatic increase in population soon made it impossible for the cities to feed all their inhabitants. Under such pressures, the Insecurity Index once again began to rise. The solution to the problem for many poleis was colonization – some would have to leave in order to prevent the starvation of the entire population. Motivated primarily by land hunger, a wave of colonization began that would eventually disseminate Greek settlers and Greek culture all over the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

The development of the poleis soon led to a falling Insecurity Index in Greece. By the 8th century B.C. mainland Greeks once again experienced rising levels of security and prosperity. The results were enormous – as people felt more secure, they began to have more children. At the same time, greater security and prosperity also made it possible for more children and young adults to actually survive into adulthood. Such prosperity, however, contained the seeds of its own destruction. The rapid and dramatic increase in population soon made it impossible for the cities to feed all their inhabitants. Under such pressures, the Insecurity Index once again began to rise. The solution to the problem for many poleis was colonization – some would have to leave in order to prevent the starvation of the entire population. Motivated primarily by land hunger, a wave of colonization began that would eventually disseminate Greek settlers and Greek culture all over the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

Land hunger may have been the primary impetus for Greek colonization but opportunities for trade and politics also played a role in decisions to go overseas. Greek colonists not only had to create their own political, social and economic systems in the new poleis they established, but they also came in contact with other cultures, which they soon realized were not necessarily inferior to their own. Although each of the new cities, like any Greek polis, was essentially independent of its mother city, most maintained cordial relations with them. In particular, most developed thriving export economies, whose chief trading partners were often the mother city. In the Black Sea region, for example, the colonies became producers and exporters of grain. In Sicily and southern Italy, they also produced olives and grapes, mostly for oil and wine.

Painted images from Greek pottery depicting a single hoplite (below) and a group of hoplites in phalanx formation (above) from http://www.livius.org/pha-phd/phalanx/phalanx.html

Painted images from Greek pottery depicting a single hoplite (below) and a group of hoplites in phalanx formation (above) from http://www.livius.org/pha-phd/phalanx/phalanx.html

Cultural Revolution

The consequences of Greek colonization were enormous. For three centuries, Greeks from the mainland left their mother cities to establish themselves on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea "like frogs around a pound" as one Greek philosopher would later put it. Colonists emigrated south and west in the 8th century, north and east in the 7th century, and in the 6th century they consolidated their existing settlements. To the east and the south they confronted the more advanced civilizations of the Near East and Egypt, from whom they learned; in the north and the west (Scythia or Italy), they came into contact with less advanced cultures, who learned from them. The result was a melting pot, an original civilization that was nevertheless able to incorporate ideas and influences from surrounding civilizations and transmit them in modified form to others. Soon, many of these new ideas began to filter back from the colonies to the mother cities in mainland Greece – the result amounted to a cultural revolution in Greek civilization.

Philosophy. Perhaps the most important development of such new ideas in this period began in the city of Miletus, on the western coast of Asia Minor - a region known as Ionia. This Ionian Enlightenment, as it is called, marked the beginning of an intellectual revolution and the birth of western philosophy. It consisted of thinkers and teachers, who would soon become known as philosophers, or “lovers of Wisdom,” who devoted themselves to reflecting on the nature of the universe and the place of man in that universe. For the first time, western man tried to understand the world rather than to feel himself simply subject to it. These first philosophers, who became known as the cosmologists, tried to understand the essence of the universe, or kosmos as it was called in Greek. Moderns may smile at their hypotheses but the importance remains that for the first time human beings tried to understand first the world and then man himself. The quest for philosophy had begun. From that moment on the Greek mind would never stop asking questions about the mysteries of life and the human condition.

Literature. One of the best indications of the changes occurring in Greek culture can be seen in the literature produced during the period. According to tradition, sometime around 750 B.C. the blind Greek poet, Homer, composed the Iliad, the story of the Trojan War. The great epic poem tells the tale of war between mainland Greeks, under the leadership of Bronze Age Mycenae, and the city of Troy on the Asian coast of the Aegean. Some 30 years later, around 720, Homer is also supposed to have composed a kind of sequel, the Odyssey, which traced the long voyage home of one of the Greek leaders, Odysseus of Ithaca, after the fall of Troy. A comparison of the two stories, however, gives a glimpse into the changes occurring in the Greek world even during Homer’s own lifetime.

The world of the Iliad is a closed world, even claustrophobic, centered entirely on the citadel of Troy. By the time of the Odyssey, on the other hand, the world has opened up. Odysseus sails freely over the whole Mediterranean. Motivations too have changed. The characters in the Iliad are guided by powers bigger than themselves, the gods, and do not really control their actions. Odysseus, "resourceful Odysseus" as Homer likes to call him, is an adventurer driven by his own curiosity who uses all his cunning to achieve his own goals. The picture of transformation during the 700s is completed by the works of Hesiod, who wrote at the very end of the century.

Hesiod was a pragmatic man writing for ordinary people about their ordinary problems. In his poem, Works and Days (700 B.C.?) he advises his brother how to become a good farmer and a better man. This is no heroic tale, but rather one of thoroughly human scale. Hesiod was especially concerned about something that would become an essential and permanent question in Greek thought—the nature of justice, and how to live a right life in a just society. Thus, by the end of the 700s, Greeks had begun to shake off their fairly limited view of life illuminated only by tales of a heroic and aristocratic bronze-age warrior society, and had instead begun to see the world from a thoroughly practical and human point of view.

Political transformations. From a political point of view the Archaic Period witnessed the decline of monarchy and an essentially aristocratic order and the birth of democracy. The earliest city-states had begun as small kingdoms centered on hilltop fortresses. Their main purpose was defense and they were consequently ruled by those who provided that defense - warrior chieftains or kings, supported by a wealthy land-owning warrior elite. Land ownership for this ruling elite was critical, since land was the source of wealth and only those with wealth could afford the expensive bronze weapons and armor, chariots and horses on which successful Bronze Age warfare depended. By the 8th century, however, the wealthy landowning warriors had taken power into their own hands, overthrowing or limiting the powers of most of the kings and establishing aristocracies throughout Greece. These land-owning aristocrats, a term meaning "best men" in Greek, controlled every aspect of Greek society: they had a monopoly over the military (no commoner fought in the Iliad), control of the economy (they owned the land), of the judiciary (they were the judges in a system of customary law), religion (the gods would not listen to commoners), culture (Epic poetry is the literature of the aristocracy), society (they set the standards of social behavior), and of course, politics (they were the only ones to govern).

During the first half of the 7th century, however, the old aristocratic dominance began to diminish. To begin with, wealth was no longer entirely concentrated in the hands of a few aristocratic families: thanks to colonization, trading and commercial opportunities had made it possible for commoners to acquire wealth. Soon they too were able to buy land. Similarly, the aristocrats lost their military monopoly with the rise of thehoplites, heavily armed infantryman equipped with iron weapons and fighting in the phalanx formation - a large body of closely packed men, each holding a long iron-tipped spear pointed outward in a kind of porcupine-looking formation. A phalanx was a formidable military formation against which cavalry, before the invention of the stirrup, was powerless. The iron weapons and equipment of the hoplite, although expensive, could not be compared with the costs of bronze weapons or the financial burden of raising, training, and outfitting warhorses. At the same time, the phalanx formation required considerably more men than the small aristocratic class alone could provide. As wealthy commoners joined the ranks of the hoplites, and the phalanx replaced the chariot and the warhorse, commoners soon realized that they were even more important to the defense (and hence the survival) of their cities than the aristocrats.

As commoners became more and more important in the military defense of the polis, they also began to demand a fairer access to justice. In place of unwritten customary laws administered by aristocratic judges, the people began to demand that laws be written down so that all could see and understand them – and could expect judicial rulings to conform to them. This general movement toward legal codification in the second half of the 7th century effectively put an end to the arbitrary rule of the aristocracy. Culturally too, the patronage of wealthy commoners led to the development of new forms of art and literature – lyric poetry, for example, focused on personal feelings and emotions that were not limited to the aristocracy: all could associate themselves with feelings of love, friendship, or nature (as opposed to the heroic ideals of aristocratic warfare portrayed in Homer). Sapho of Lesbos, Archilochus of Paros, Terpander, to name only a few, ushered in what became known as the "Lyric Age of Greece".

The consequences of Greek colonization were enormous. For three centuries, Greeks from the mainland left their mother cities to establish themselves on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea "like frogs around a pound" as one Greek philosopher would later put it. Colonists emigrated south and west in the 8th century, north and east in the 7th century, and in the 6th century they consolidated their existing settlements. To the east and the south they confronted the more advanced civilizations of the Near East and Egypt, from whom they learned; in the north and the west (Scythia or Italy), they came into contact with less advanced cultures, who learned from them. The result was a melting pot, an original civilization that was nevertheless able to incorporate ideas and influences from surrounding civilizations and transmit them in modified form to others. Soon, many of these new ideas began to filter back from the colonies to the mother cities in mainland Greece – the result amounted to a cultural revolution in Greek civilization.

Philosophy. Perhaps the most important development of such new ideas in this period began in the city of Miletus, on the western coast of Asia Minor - a region known as Ionia. This Ionian Enlightenment, as it is called, marked the beginning of an intellectual revolution and the birth of western philosophy. It consisted of thinkers and teachers, who would soon become known as philosophers, or “lovers of Wisdom,” who devoted themselves to reflecting on the nature of the universe and the place of man in that universe. For the first time, western man tried to understand the world rather than to feel himself simply subject to it. These first philosophers, who became known as the cosmologists, tried to understand the essence of the universe, or kosmos as it was called in Greek. Moderns may smile at their hypotheses but the importance remains that for the first time human beings tried to understand first the world and then man himself. The quest for philosophy had begun. From that moment on the Greek mind would never stop asking questions about the mysteries of life and the human condition.

Literature. One of the best indications of the changes occurring in Greek culture can be seen in the literature produced during the period. According to tradition, sometime around 750 B.C. the blind Greek poet, Homer, composed the Iliad, the story of the Trojan War. The great epic poem tells the tale of war between mainland Greeks, under the leadership of Bronze Age Mycenae, and the city of Troy on the Asian coast of the Aegean. Some 30 years later, around 720, Homer is also supposed to have composed a kind of sequel, the Odyssey, which traced the long voyage home of one of the Greek leaders, Odysseus of Ithaca, after the fall of Troy. A comparison of the two stories, however, gives a glimpse into the changes occurring in the Greek world even during Homer’s own lifetime.

The world of the Iliad is a closed world, even claustrophobic, centered entirely on the citadel of Troy. By the time of the Odyssey, on the other hand, the world has opened up. Odysseus sails freely over the whole Mediterranean. Motivations too have changed. The characters in the Iliad are guided by powers bigger than themselves, the gods, and do not really control their actions. Odysseus, "resourceful Odysseus" as Homer likes to call him, is an adventurer driven by his own curiosity who uses all his cunning to achieve his own goals. The picture of transformation during the 700s is completed by the works of Hesiod, who wrote at the very end of the century.

Hesiod was a pragmatic man writing for ordinary people about their ordinary problems. In his poem, Works and Days (700 B.C.?) he advises his brother how to become a good farmer and a better man. This is no heroic tale, but rather one of thoroughly human scale. Hesiod was especially concerned about something that would become an essential and permanent question in Greek thought—the nature of justice, and how to live a right life in a just society. Thus, by the end of the 700s, Greeks had begun to shake off their fairly limited view of life illuminated only by tales of a heroic and aristocratic bronze-age warrior society, and had instead begun to see the world from a thoroughly practical and human point of view.

Political transformations. From a political point of view the Archaic Period witnessed the decline of monarchy and an essentially aristocratic order and the birth of democracy. The earliest city-states had begun as small kingdoms centered on hilltop fortresses. Their main purpose was defense and they were consequently ruled by those who provided that defense - warrior chieftains or kings, supported by a wealthy land-owning warrior elite. Land ownership for this ruling elite was critical, since land was the source of wealth and only those with wealth could afford the expensive bronze weapons and armor, chariots and horses on which successful Bronze Age warfare depended. By the 8th century, however, the wealthy landowning warriors had taken power into their own hands, overthrowing or limiting the powers of most of the kings and establishing aristocracies throughout Greece. These land-owning aristocrats, a term meaning "best men" in Greek, controlled every aspect of Greek society: they had a monopoly over the military (no commoner fought in the Iliad), control of the economy (they owned the land), of the judiciary (they were the judges in a system of customary law), religion (the gods would not listen to commoners), culture (Epic poetry is the literature of the aristocracy), society (they set the standards of social behavior), and of course, politics (they were the only ones to govern).

During the first half of the 7th century, however, the old aristocratic dominance began to diminish. To begin with, wealth was no longer entirely concentrated in the hands of a few aristocratic families: thanks to colonization, trading and commercial opportunities had made it possible for commoners to acquire wealth. Soon they too were able to buy land. Similarly, the aristocrats lost their military monopoly with the rise of thehoplites, heavily armed infantryman equipped with iron weapons and fighting in the phalanx formation - a large body of closely packed men, each holding a long iron-tipped spear pointed outward in a kind of porcupine-looking formation. A phalanx was a formidable military formation against which cavalry, before the invention of the stirrup, was powerless. The iron weapons and equipment of the hoplite, although expensive, could not be compared with the costs of bronze weapons or the financial burden of raising, training, and outfitting warhorses. At the same time, the phalanx formation required considerably more men than the small aristocratic class alone could provide. As wealthy commoners joined the ranks of the hoplites, and the phalanx replaced the chariot and the warhorse, commoners soon realized that they were even more important to the defense (and hence the survival) of their cities than the aristocrats.

As commoners became more and more important in the military defense of the polis, they also began to demand a fairer access to justice. In place of unwritten customary laws administered by aristocratic judges, the people began to demand that laws be written down so that all could see and understand them – and could expect judicial rulings to conform to them. This general movement toward legal codification in the second half of the 7th century effectively put an end to the arbitrary rule of the aristocracy. Culturally too, the patronage of wealthy commoners led to the development of new forms of art and literature – lyric poetry, for example, focused on personal feelings and emotions that were not limited to the aristocracy: all could associate themselves with feelings of love, friendship, or nature (as opposed to the heroic ideals of aristocratic warfare portrayed in Homer). Sapho of Lesbos, Archilochus of Paros, Terpander, to name only a few, ushered in what became known as the "Lyric Age of Greece".

ATHENS IN THE ARCHAIC AGE

By the seventh century B.C., Athens had brought all the cities and villages of Attica under her dominion. A polis in control of a large territory, Athens had been able to integrate the demographic growth of the 8th century without resorting to colonization. She had been less disturbed by the new social and economic conditions that had shaken the rest of Greece. And yet, the attempt of Cylon to establish himself as a tyrant (ca. 632 B.C.) and the promulgation of a code of laws by Draco (ca. 621 B.C.) show that she was not immune from the general movement against aristocratic privileges and hegemony.

Although Attica remained essentially an agricultural society and aristocratic families well established in the countryside were able to keep a better control over the population than in other smaller poleis, the crisis that exploded at the end of the 600s came from the gap in wealth between the aristocrats and the rest of the population. Poor farmers were over-burdened with debt and sometimes reduced to slavery when unable to repay their creditors. At the same time, since land ownership was a pre-requisite for participation in the army, the consolidation of land ownership in fewer and fewer hands meant also a reduction in the size of the citizen army. The combination of growing internal social unrest and vulnerability to external attack became so dangerous that the aristocrats decided to elect one of their members to be a mediator with absolute power to resolve the crisis. Their choice fell on Solon, who was elected to the chief magistracy for the year 594 B.C.

Solon’s reforms. Using his emergency authority, Solon carried out a vast range of reforms. To begin with, he cancelled all existing debts and restored the freedom of those who had fallen into slavery. In economic matters he tried to make Athens less dependent on agriculture by a series of reforms designed to encourage trade, commerce and industry. In politics his reforms were far more dramatic - he changed the political order from aristocracy to timocracy, a form of government in which the tenure of political offices depends on property qualifications. He divided the whole citizenry into four classes according to their wealth. The two wealthiest classes were eligible for the highest magistracies; the third could be elected to minor offices; the last category, although debarred from being elected to any public offices were given the right to elect candidates and pass legislation in the assembly (ecclesia). In a stroke, the monopoly the nobility had held on the political power of the state was broken.

Bust titled 'Solon' (National Museum, Naples)

c.638-558 BC, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solon

Solon's political reforms were astute. He had successfully opened the doors of political power to the new class of rich commoners without precipitating a complete revolution. Since aristocrats remained the wealthiest members of Athenian society his reforms did not suddenly deprive them of power and influence but only required that they share it. Similarly, he refused to bow to popular demands for the confiscation and redistribution of land, a measure he considered unjust and too revolutionary. On the other hand, Solon had not solved all the problems and had left many people, both rich and poor, unsatisfied. Athens grew economically in the decades following his reforms but not without increasing social tensions.

The Pisistratid tyranny. In 546 these tensions once again reached such a fever pitch that an aristocrat named Pisistratus, by appealing for support from the merchants and commoners, was able to short-circuit the electoral process and to take power illegally, though with a majority of popular support – a form of government that the ancient Greeks called tyranny.

Under the rule of Pisistratus and his sons (546-510 B.C.) Athens would know a period of relative political stability and economic prosperity. The Pisistratids (as the dynasty is called) curbed the power of the aristocracy and favored their natural allies, the merchants and the common people. On the other end, they did not overturn Solon's reforms. They left the popular assembly to elect magistrates and pass legislation, but only to the extent that they elected the Pisistratids’ own candidates and passed laws to which the tyrants did not object. Ironically, perhaps, by allowing this kind of controlled constitutional activity, the Pisistratids were actually giving people a chance to learn the technicalities of popular decision-making. Moreover, by forcing equality of all under the rule of one, they increased the sense of community in Athens. All citizens, poor and rich, aristocrats and commoners, were equal under the tyrant.

The Pisistratids were also important because they centralized Attica around Athens. They wanted the population to feel more attached to the city than to the countryside where the aristocrats were still powerful. An important program of civic building and the creation and development of civic festivals gave the Athenians a sense of pride in their city.

In 514, Hipparchus, one of the sons of Pisistratus, was murdered and his brother Hippias became afraid for his own life. Hippias then truly acted like a tyrant in the modern sense of the word. As he persecuted his supposed enemies, the people of Athens began to realize the true potential nature of tyranny. Eventually they revolted and in 510 they forced Hippias into exile. Athens thus recovered her freedom. Since the tyranny had essentially overthrown both the old aristocracy and even the notion of timocracy that had developed under Solon, the way was now open for yet another experiment in self-government – democracy.

Cleisthenes and democracy. The man who carried through the last important political reforms of the Archaic Age in Athens by instituting democracy was Cleisthenes (508 B.C.). Cleisthenes kept the four classes established by Solon, though he included movable property in the computation of a citizen’s wealth. In addition, however, Cleisthenes divided the Athenian population into ten new tribes. These tribes were based on residency, but each included a mix of people from the city, the interior and the coast. In this way Cleisthenes hoped to destroy the regional power of the aristocracy once and for all. He also created a new council of Five Hundred that was to prepare all matters to be presented to the popular assembly: every month (the Athenian year was divided into ten months), a different tribe was in charge of this council, which was composed of 50 citizens chosen by lot. The Athenians considered the lot more democratic than elections. Nobody could serve in this council more than twice in his life, so that as many people as possible would have a chance to serve. But all the legislative and electoral power remained with the ecclesia. Thus Athens became what modern scholars call a 'direct democracy'. The people were not represented by elected delegates (as in modern democratic/republican systems), but participated directly in all major decisions and public offices.

By the seventh century B.C., Athens had brought all the cities and villages of Attica under her dominion. A polis in control of a large territory, Athens had been able to integrate the demographic growth of the 8th century without resorting to colonization. She had been less disturbed by the new social and economic conditions that had shaken the rest of Greece. And yet, the attempt of Cylon to establish himself as a tyrant (ca. 632 B.C.) and the promulgation of a code of laws by Draco (ca. 621 B.C.) show that she was not immune from the general movement against aristocratic privileges and hegemony.

Although Attica remained essentially an agricultural society and aristocratic families well established in the countryside were able to keep a better control over the population than in other smaller poleis, the crisis that exploded at the end of the 600s came from the gap in wealth between the aristocrats and the rest of the population. Poor farmers were over-burdened with debt and sometimes reduced to slavery when unable to repay their creditors. At the same time, since land ownership was a pre-requisite for participation in the army, the consolidation of land ownership in fewer and fewer hands meant also a reduction in the size of the citizen army. The combination of growing internal social unrest and vulnerability to external attack became so dangerous that the aristocrats decided to elect one of their members to be a mediator with absolute power to resolve the crisis. Their choice fell on Solon, who was elected to the chief magistracy for the year 594 B.C.

Solon’s reforms. Using his emergency authority, Solon carried out a vast range of reforms. To begin with, he cancelled all existing debts and restored the freedom of those who had fallen into slavery. In economic matters he tried to make Athens less dependent on agriculture by a series of reforms designed to encourage trade, commerce and industry. In politics his reforms were far more dramatic - he changed the political order from aristocracy to timocracy, a form of government in which the tenure of political offices depends on property qualifications. He divided the whole citizenry into four classes according to their wealth. The two wealthiest classes were eligible for the highest magistracies; the third could be elected to minor offices; the last category, although debarred from being elected to any public offices were given the right to elect candidates and pass legislation in the assembly (ecclesia). In a stroke, the monopoly the nobility had held on the political power of the state was broken.

Bust titled 'Solon' (National Museum, Naples)

c.638-558 BC, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solon

Solon's political reforms were astute. He had successfully opened the doors of political power to the new class of rich commoners without precipitating a complete revolution. Since aristocrats remained the wealthiest members of Athenian society his reforms did not suddenly deprive them of power and influence but only required that they share it. Similarly, he refused to bow to popular demands for the confiscation and redistribution of land, a measure he considered unjust and too revolutionary. On the other hand, Solon had not solved all the problems and had left many people, both rich and poor, unsatisfied. Athens grew economically in the decades following his reforms but not without increasing social tensions.

The Pisistratid tyranny. In 546 these tensions once again reached such a fever pitch that an aristocrat named Pisistratus, by appealing for support from the merchants and commoners, was able to short-circuit the electoral process and to take power illegally, though with a majority of popular support – a form of government that the ancient Greeks called tyranny.

Under the rule of Pisistratus and his sons (546-510 B.C.) Athens would know a period of relative political stability and economic prosperity. The Pisistratids (as the dynasty is called) curbed the power of the aristocracy and favored their natural allies, the merchants and the common people. On the other end, they did not overturn Solon's reforms. They left the popular assembly to elect magistrates and pass legislation, but only to the extent that they elected the Pisistratids’ own candidates and passed laws to which the tyrants did not object. Ironically, perhaps, by allowing this kind of controlled constitutional activity, the Pisistratids were actually giving people a chance to learn the technicalities of popular decision-making. Moreover, by forcing equality of all under the rule of one, they increased the sense of community in Athens. All citizens, poor and rich, aristocrats and commoners, were equal under the tyrant.

The Pisistratids were also important because they centralized Attica around Athens. They wanted the population to feel more attached to the city than to the countryside where the aristocrats were still powerful. An important program of civic building and the creation and development of civic festivals gave the Athenians a sense of pride in their city.

In 514, Hipparchus, one of the sons of Pisistratus, was murdered and his brother Hippias became afraid for his own life. Hippias then truly acted like a tyrant in the modern sense of the word. As he persecuted his supposed enemies, the people of Athens began to realize the true potential nature of tyranny. Eventually they revolted and in 510 they forced Hippias into exile. Athens thus recovered her freedom. Since the tyranny had essentially overthrown both the old aristocracy and even the notion of timocracy that had developed under Solon, the way was now open for yet another experiment in self-government – democracy.

Cleisthenes and democracy. The man who carried through the last important political reforms of the Archaic Age in Athens by instituting democracy was Cleisthenes (508 B.C.). Cleisthenes kept the four classes established by Solon, though he included movable property in the computation of a citizen’s wealth. In addition, however, Cleisthenes divided the Athenian population into ten new tribes. These tribes were based on residency, but each included a mix of people from the city, the interior and the coast. In this way Cleisthenes hoped to destroy the regional power of the aristocracy once and for all. He also created a new council of Five Hundred that was to prepare all matters to be presented to the popular assembly: every month (the Athenian year was divided into ten months), a different tribe was in charge of this council, which was composed of 50 citizens chosen by lot. The Athenians considered the lot more democratic than elections. Nobody could serve in this council more than twice in his life, so that as many people as possible would have a chance to serve. But all the legislative and electoral power remained with the ecclesia. Thus Athens became what modern scholars call a 'direct democracy'. The people were not represented by elected delegates (as in modern democratic/republican systems), but participated directly in all major decisions and public offices.

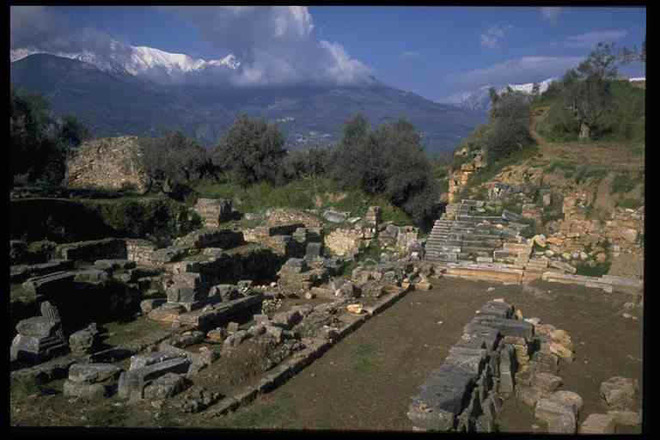

Ruins of the acropolis at Sparta, from http://www.fjkluth.com/sparta.html#Pict

Ruins of the acropolis at Sparta, from http://www.fjkluth.com/sparta.html#Pict

SPARTA IN THE ARCHAIC AGE

Not all Greek city-states followed the same evolution toward democracy as Athens. And ironically, although later Western civilization would hold Athenian democracy up as the ideal of classical Greek civilization and the foundation of the West's own rise to both civilization and ultimately to democratic systems of government, for most Greeks at the time a very different model commanded greater respect - that of Sparta. We have little information concerning the vast majority of the Greek poleis but, like Athens, Sparta is an exception: its political and social system is well known since it gained a great reputation for its stability and order.

Unlike Athens, Sparta is said to have received a constitution early in her history, a constitution associated with the legendary figure of Lycurgus. The later biographer Plutarch recorded that "everything concerning Lycurgus is subject to controversy" and his judgment still holds true. In its historical form, Sparta’s political order was composed of four institutions: [1] two kings (two different dynasties) had important religious and military powers. [2] They were assisted by a council of 28 citizens, 60 years old and older (the gerousia), a council that prepared business to be presented to the assembly of the citizens. [3] Five magistrates charged with the daily affairs of the state, and [4] the assembly of the citizens (Apella) which, at first, had the power to decide in last resort on every important matters. The members of the popular assembly were free male citizens 30 years old and older. They were known as the "equals" since in Sparta there was no aristocratic order nor economic inequality (each citizen received a farm from the state).

This system soon changed, however, and the people lost power to the kings and the Gerousia through an amendment to the constitution that allowed the kings and the council of elders to ignore any decisions made by the people if they judged them unwise or inappropriate. At any rate, the Spartan state was very stable and not until the fourth century did any opposition appear to challenge the Lycurgan order. This political stability, as well as the complete equality enjoyed by all Spartan citizens, made Sparta the image of a well-ordered state worthy of praise and imitation for most other Greeks.

A military state. Sparta was also renowned for her military might. Indeed Sparta was a military state, whose citizens were totally dedicated to war. In the eighth century, the Spartans took control of their neighbors in Laconia and Messenia. This made of Sparta the largest power in Greece and gave her economic independence. It also dictated the nature of Spartan society as well.

After the conquest Spartan society was divided into three categories: the "equals," free citizens with political rights; the so-called "half-citizens" (perioikoi), free population from nearby communities dependent on Sparta, who paid taxes and might serve in the army but had no political rights; and the helots, or state slaves, made up of captives from wars and above all, the conquered Laconians and Messenians. While the helots worked the farms given to each citizen by the state, the half-citizens concentrated on commercial and industrial activities. Thus the equals were freed from any need to engage in economic activities to support themselves - instead, they devoted all their time to military training. Such military training was mandatory under the Spartan constitution and vital to the state's survival because the helots outnumbered Spartan citizens by 7 to 1 - and were always ready to revolt. Consequently, the Spartans lived in a permanent state of emergency, always ready to face uprisings from the rest of the population. With such a constantly high Insecurity Index, Sparta inevitably became a military state that kept the majority of its population under control with a deliberate policy of brutality and terror. Indeed, once a year the Spartans formally declared war on their helots, a practice that gave equals the right to kill helots for any reason, without legal penalty.

Education and Spartan culture. The Spartan system of education was entirely focused on physical fitness and military training. At birth the child (male or female) was examined by a council of elders. If considered sickly the baby was exposed in the near by mountains until it died. Sparta could not afford unfit citizens.

From age seven to eighteen, boys trained intensively in what might be called early "boot-camps." From 18 to 20, they trained specifically for war. From age 20 to 30 all Spartan men were full time soldiers, living with their companions in barracks. Only after the age of 30 could a Spartan go home at night. Even then he remained in the military and until 60 had to take at least one meal every day with his fellow soldiers. He could get married at 20 but could not live with his wife and family before 30. As for women, they too underwent intensive physical training. Their primary role in Spartan society was to bear future soldiers and provide them with their early training.

As might be expected, the Spartan educational system made some of the best soldiers the world had known. On the other hand, military might was achieved at the expense of other activities. Spartans had virtually no interest in the arts, philosophy, or any other form of civilized culture. Only in sports, whose primary purpose was to provide conditioning and training for war, did Spartan athletes excel.

WEB RESOURCE: Ancient Greek Cities

Not all Greek city-states followed the same evolution toward democracy as Athens. And ironically, although later Western civilization would hold Athenian democracy up as the ideal of classical Greek civilization and the foundation of the West's own rise to both civilization and ultimately to democratic systems of government, for most Greeks at the time a very different model commanded greater respect - that of Sparta. We have little information concerning the vast majority of the Greek poleis but, like Athens, Sparta is an exception: its political and social system is well known since it gained a great reputation for its stability and order.

Unlike Athens, Sparta is said to have received a constitution early in her history, a constitution associated with the legendary figure of Lycurgus. The later biographer Plutarch recorded that "everything concerning Lycurgus is subject to controversy" and his judgment still holds true. In its historical form, Sparta’s political order was composed of four institutions: [1] two kings (two different dynasties) had important religious and military powers. [2] They were assisted by a council of 28 citizens, 60 years old and older (the gerousia), a council that prepared business to be presented to the assembly of the citizens. [3] Five magistrates charged with the daily affairs of the state, and [4] the assembly of the citizens (Apella) which, at first, had the power to decide in last resort on every important matters. The members of the popular assembly were free male citizens 30 years old and older. They were known as the "equals" since in Sparta there was no aristocratic order nor economic inequality (each citizen received a farm from the state).

This system soon changed, however, and the people lost power to the kings and the Gerousia through an amendment to the constitution that allowed the kings and the council of elders to ignore any decisions made by the people if they judged them unwise or inappropriate. At any rate, the Spartan state was very stable and not until the fourth century did any opposition appear to challenge the Lycurgan order. This political stability, as well as the complete equality enjoyed by all Spartan citizens, made Sparta the image of a well-ordered state worthy of praise and imitation for most other Greeks.

A military state. Sparta was also renowned for her military might. Indeed Sparta was a military state, whose citizens were totally dedicated to war. In the eighth century, the Spartans took control of their neighbors in Laconia and Messenia. This made of Sparta the largest power in Greece and gave her economic independence. It also dictated the nature of Spartan society as well.

After the conquest Spartan society was divided into three categories: the "equals," free citizens with political rights; the so-called "half-citizens" (perioikoi), free population from nearby communities dependent on Sparta, who paid taxes and might serve in the army but had no political rights; and the helots, or state slaves, made up of captives from wars and above all, the conquered Laconians and Messenians. While the helots worked the farms given to each citizen by the state, the half-citizens concentrated on commercial and industrial activities. Thus the equals were freed from any need to engage in economic activities to support themselves - instead, they devoted all their time to military training. Such military training was mandatory under the Spartan constitution and vital to the state's survival because the helots outnumbered Spartan citizens by 7 to 1 - and were always ready to revolt. Consequently, the Spartans lived in a permanent state of emergency, always ready to face uprisings from the rest of the population. With such a constantly high Insecurity Index, Sparta inevitably became a military state that kept the majority of its population under control with a deliberate policy of brutality and terror. Indeed, once a year the Spartans formally declared war on their helots, a practice that gave equals the right to kill helots for any reason, without legal penalty.

Education and Spartan culture. The Spartan system of education was entirely focused on physical fitness and military training. At birth the child (male or female) was examined by a council of elders. If considered sickly the baby was exposed in the near by mountains until it died. Sparta could not afford unfit citizens.

From age seven to eighteen, boys trained intensively in what might be called early "boot-camps." From 18 to 20, they trained specifically for war. From age 20 to 30 all Spartan men were full time soldiers, living with their companions in barracks. Only after the age of 30 could a Spartan go home at night. Even then he remained in the military and until 60 had to take at least one meal every day with his fellow soldiers. He could get married at 20 but could not live with his wife and family before 30. As for women, they too underwent intensive physical training. Their primary role in Spartan society was to bear future soldiers and provide them with their early training.

As might be expected, the Spartan educational system made some of the best soldiers the world had known. On the other hand, military might was achieved at the expense of other activities. Spartans had virtually no interest in the arts, philosophy, or any other form of civilized culture. Only in sports, whose primary purpose was to provide conditioning and training for war, did Spartan athletes excel.

WEB RESOURCE: Ancient Greek Cities