Chapter 11

A New Civilization in Western Europe:

the Rise of Latin Christendom, 476-1350

Section 1 The Emergence of the Franks

Rome had fallen. The legions were no more. Grass grew tall between the broken paving stones of the great forum. Where once the Caesars had ruled, Germanic kings now feasted on the spoils of empire. Yet people still held the Roman Empire in awe. Many of the new Germanic kings sought recognition from the remaining emperor in Constantinople as a sign of their legitimacy. Such efforts, however, could not hide the fact that Roman urban civilization had collapsed in Western Europe. In its place, a new civilization was emerging that drew on German traditions for its strength and vigor, Roman traditions for its vision of a universal state, and Christian traditions for the socio-religious identity that would hold everything together.

The Germanic Invaders

The Ostrogoths and Visigoths who overthrew the western provinces of the empire had long lived in the shadow of the Roman world. After they took power, the kings of these Germanic peoples retained their respect for the empire’s laws and traditions. Theodoric the Great, for example, an Ostrogothic king who ruled Italy from 493 to 526, maintained the senate and the old imperial administration and ruled according to Roman law. As the great migrations continued, however, many other Germanic peoples flooded into the western provinces behind the Ostrogoths and Visigoths. Largely untouched by Romanization, these Franks, Angles, Saxons, and others who established kingdoms in the old Roman provinces of northern Gaul and Britain in the 400s, retained their pagan beliefs and German customs.

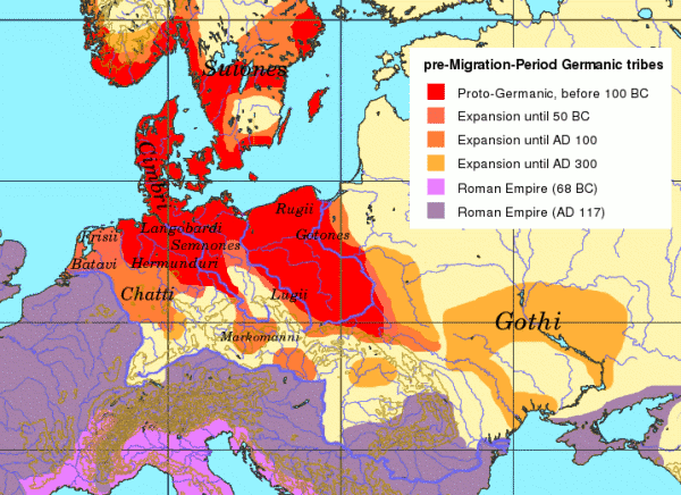

German origins. We know little of the Germans' origins, since they did not develop a written language of their own until after contact with the Roman world. Culturally and linguistically, they were part of the great Indo-European group of peoples. Archaeological evidence indicates that they settled in Scandinavia and along the southern shores of the Baltic Sea between the Oder and Elbe Rivers as early as 750 B.C. From this southern region, some Germanic peoples, including the Saxons and Franks, moved west, reaching the Rhine River about 250 B.C. Also in the 200s a third group, including the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, and Vandals, crossed over the Baltic Sea from Scandinavia, settling between the Oder and Vistula Rivers in northeastern Europe. These eastern Germans gradually spread south to the shores of the Black Sea and the banks of the lower Danube River.

No higher resolution available. Pre_Migration_Age_Germanic.png (600 × 436 pixels, file size: 94 KB, MIME type: image/png) This is a file from the Wikimedia Commons.

Family and cultural values. The Germans who invaded northern Europe were migratory, moving when necessary to guarantee food supplies or when threatened by invaders. They were not completely nomadic, however, and often settled in an area for generations. They lived in crude huts grouped together in small villages carved out of the forests. They survived by hunting and fishing in the region’s great forests and rivers and by herding cattle, sheep, and pigs. Warlike, they often raided their neighbors.

The Germans organized themselves into kinship groups. Primary loyalties were to the family, the clan, and sometimes to a larger tribal grouping, though such tribes seem to have developed primarily during times of warfare or other emergency, and could easily dissolve or be re-formed by a different set of clans. The heads of the wealthiest families, including chieftains whose families claimed descent from the gods, ruled the villages through councils. These leading aristocratic families also often acted as patrons to less wealthy families, helping them with money or support against their enemies in exchange for political and military loyalty.[2]

The Germans were patriarchal and fathers ruled over their families with complete authority. Those men who could afford them often had several wives. German women were primarily responsible for raising the children, preparing food and beer, spinning thread, and weaving cloth. They were also held in high esteem, however, and often had a voice in tribal affairs. Germans even believed, wrote the Roman historian Tacitus around A.D. 100, “that in women is a certain uncanny and prophetic sense: they neither scorn to consult them nor slight their answers.” Tacitus also reported that German women supported their men on the battlefield, bringing them food and encouraging the warriors to be brave.[3]

As with the pre-Islamic Arabs, the Germans developed values that reflected their struggle for survival in a harsh environment. They prized generosity, for example, and friendship was extremely important. According to Tacitus:

"No race indulges more lavishly in hospitality and entertainment. To close the door against any human being is a crime. Everyone according to his means welcomes guests generously. Should there not be enough, he who is your host goes with you next door, without an invitation, but it makes no difference; you are received with the same courtesy."[4]

Despite this emphasis on generosity and friendship, Germanic society recognized different levels of status. For example, individuals gained status according to the number of cattle they owned or their leadership abilities in war.

War and social structure. Since the early Germans were migratory raiders, they were organized for fighting. This organization continued even after they began to settle down. In times of crisis, tribal assemblies chose war leaders from the most powerful families. These tribal chiefs organized bands of warriors who took solemn oaths of personal loyalty, faithfulness, and obedience to their leader. In return the chief promised to provide them with food and drink and a share in the booty.

Once the tribes moved into the Roman Empire, many of the war chiefs established themselves as kings. They distributed much of the land they conquered to their warriors, who thus became landed nobles. Under the king and nobles were freemen. Freemen could own land and had some political rights. Beneath them were several groups of semi-free peasants, who were generally tied to working the land. At the bottom of society, captives taken in raids became slaves, as did some who had to sell themselves to pay off their debts.[5]

A New Civilization in Western Europe:

the Rise of Latin Christendom, 476-1350

Section 1 The Emergence of the Franks

Rome had fallen. The legions were no more. Grass grew tall between the broken paving stones of the great forum. Where once the Caesars had ruled, Germanic kings now feasted on the spoils of empire. Yet people still held the Roman Empire in awe. Many of the new Germanic kings sought recognition from the remaining emperor in Constantinople as a sign of their legitimacy. Such efforts, however, could not hide the fact that Roman urban civilization had collapsed in Western Europe. In its place, a new civilization was emerging that drew on German traditions for its strength and vigor, Roman traditions for its vision of a universal state, and Christian traditions for the socio-religious identity that would hold everything together.

The Germanic Invaders

The Ostrogoths and Visigoths who overthrew the western provinces of the empire had long lived in the shadow of the Roman world. After they took power, the kings of these Germanic peoples retained their respect for the empire’s laws and traditions. Theodoric the Great, for example, an Ostrogothic king who ruled Italy from 493 to 526, maintained the senate and the old imperial administration and ruled according to Roman law. As the great migrations continued, however, many other Germanic peoples flooded into the western provinces behind the Ostrogoths and Visigoths. Largely untouched by Romanization, these Franks, Angles, Saxons, and others who established kingdoms in the old Roman provinces of northern Gaul and Britain in the 400s, retained their pagan beliefs and German customs.

German origins. We know little of the Germans' origins, since they did not develop a written language of their own until after contact with the Roman world. Culturally and linguistically, they were part of the great Indo-European group of peoples. Archaeological evidence indicates that they settled in Scandinavia and along the southern shores of the Baltic Sea between the Oder and Elbe Rivers as early as 750 B.C. From this southern region, some Germanic peoples, including the Saxons and Franks, moved west, reaching the Rhine River about 250 B.C. Also in the 200s a third group, including the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, and Vandals, crossed over the Baltic Sea from Scandinavia, settling between the Oder and Vistula Rivers in northeastern Europe. These eastern Germans gradually spread south to the shores of the Black Sea and the banks of the lower Danube River.

No higher resolution available. Pre_Migration_Age_Germanic.png (600 × 436 pixels, file size: 94 KB, MIME type: image/png) This is a file from the Wikimedia Commons.

Family and cultural values. The Germans who invaded northern Europe were migratory, moving when necessary to guarantee food supplies or when threatened by invaders. They were not completely nomadic, however, and often settled in an area for generations. They lived in crude huts grouped together in small villages carved out of the forests. They survived by hunting and fishing in the region’s great forests and rivers and by herding cattle, sheep, and pigs. Warlike, they often raided their neighbors.

The Germans organized themselves into kinship groups. Primary loyalties were to the family, the clan, and sometimes to a larger tribal grouping, though such tribes seem to have developed primarily during times of warfare or other emergency, and could easily dissolve or be re-formed by a different set of clans. The heads of the wealthiest families, including chieftains whose families claimed descent from the gods, ruled the villages through councils. These leading aristocratic families also often acted as patrons to less wealthy families, helping them with money or support against their enemies in exchange for political and military loyalty.[2]

The Germans were patriarchal and fathers ruled over their families with complete authority. Those men who could afford them often had several wives. German women were primarily responsible for raising the children, preparing food and beer, spinning thread, and weaving cloth. They were also held in high esteem, however, and often had a voice in tribal affairs. Germans even believed, wrote the Roman historian Tacitus around A.D. 100, “that in women is a certain uncanny and prophetic sense: they neither scorn to consult them nor slight their answers.” Tacitus also reported that German women supported their men on the battlefield, bringing them food and encouraging the warriors to be brave.[3]

As with the pre-Islamic Arabs, the Germans developed values that reflected their struggle for survival in a harsh environment. They prized generosity, for example, and friendship was extremely important. According to Tacitus:

"No race indulges more lavishly in hospitality and entertainment. To close the door against any human being is a crime. Everyone according to his means welcomes guests generously. Should there not be enough, he who is your host goes with you next door, without an invitation, but it makes no difference; you are received with the same courtesy."[4]

Despite this emphasis on generosity and friendship, Germanic society recognized different levels of status. For example, individuals gained status according to the number of cattle they owned or their leadership abilities in war.

War and social structure. Since the early Germans were migratory raiders, they were organized for fighting. This organization continued even after they began to settle down. In times of crisis, tribal assemblies chose war leaders from the most powerful families. These tribal chiefs organized bands of warriors who took solemn oaths of personal loyalty, faithfulness, and obedience to their leader. In return the chief promised to provide them with food and drink and a share in the booty.

Once the tribes moved into the Roman Empire, many of the war chiefs established themselves as kings. They distributed much of the land they conquered to their warriors, who thus became landed nobles. Under the king and nobles were freemen. Freemen could own land and had some political rights. Beneath them were several groups of semi-free peasants, who were generally tied to working the land. At the bottom of society, captives taken in raids became slaves, as did some who had to sell themselves to pay off their debts.[5]

Germanic law. As Germanic society became increasingly class based, kings and nobles began to exercise power even in times of peace. Although they eventually established kingdoms, the Germans had no concept of a state that enforced the same laws on everyone. Each Germanic people established its own list of offenses and appropriate penalties. When people committed offenses, the injured parties and their families handled the matter, generally by seeking revenge on the offenders and their kin. Thus the threat of blood feuds was always present. Since such feuds were destructive, the Germans eventually devised the same alternative used by many tribal peoples—the substitution of blood money as compensation for the injury.

As they conquered non-German peoples, the Germans did not try to impose their own legal system on their new subjects. Instead, former Roman citizens were allowed to continue using Roman laws. Gradually Roman law and Germanic custom began to blend. Since the majority of the population was non-German, however, the more sophisticated and flexible Roman tradition remained a part of European society even under Germanic rule.

German Successor States to the western Roman Empire. Taken from http://homepages.udayton.edu/~schuerwc/German_kingdons.jpg

As they conquered non-German peoples, the Germans did not try to impose their own legal system on their new subjects. Instead, former Roman citizens were allowed to continue using Roman laws. Gradually Roman law and Germanic custom began to blend. Since the majority of the population was non-German, however, the more sophisticated and flexible Roman tradition remained a part of European society even under Germanic rule.

German Successor States to the western Roman Empire. Taken from http://homepages.udayton.edu/~schuerwc/German_kingdons.jpg

St. Hilda, Abbess of Whitby

St. Hilda, Abbess of Whitby

The Rise of Latin Christendom

To a large degree, German acceptance of Roman influences was made possible by the one great imperial institution to survive intact—the Church. In theory, the Church was organized along the lines of the Roman imperial administrative system: every diocese was headed by a bishop, and every province, made up of many dioceses, was headed by an archbishop. The bishop of Rome, who was called the pope, from the Latin word for “father,” was generally acknowledged as the head of the church – at least in the western provinces.

When the Roman imperial system failed in the western parts of the Empire, the Church took over. Soon, Church officials exercised secular as well as spiritual authority in many cities of the old imperial heartland, as bishops took over the functions that had been performed by imperial magistrates. Beyond the city walls, however, even the authority of the bishops did not, at first, run far.

Although the Church had generally survived the collapse of the Roman state thanks to the faith of its members, its continued existence as a unified institution was by no means certain. For one thing, most of the Germanic groups overrunning the western provinces were either still pagans or converts to the Arian form of Christianity the Church had branded heretical. Moreover, even as the official state religion of the empire, Christianity had not fully established itself beyond the walls of the empire's major cities, particularly in northwestern Europe.

North of the Alps in particular, Church organization was either non-existent or in a state of chaos; and most of the territories north of the Danube River had never been Christianized at all. Consequently, after the collapse of imperial authority, bishops often found themselves dependent on the local Germanic kings and warlords for their positions and their security. The pope's authority to appoint and remove bishops had not yet been fully accepted. Hoping to control the Church's power and influence for their own benefit, Germanic kings frequently appointed bishops from among their own families and supporters, or sold the appointments to the highest bidder.

Yet even as the Church increasingly found itself drawn into such local politics, often compromising its own moral and religious teachings, its message of salvation seemed more and more appropriate to the times. As peoples' lives became less and less secure, the church taught that earthly existence was only a step toward a better life to come. Not only did this message comfort the Christian Roman population, but in the 400s and 500s, it even began to move beyond the old Roman world. Both the survival of the organized Church and the spread of Catholic Christianity were largely due to the growth of a new movement in western Europe - monasticism.

The influence of monasticism. Christian monasticism had begun in the Eastern Empire, particularly in Egypt, in the late 200s, largely as a reaction to the success of Christianity and its acceptance by the Roman state. Individual men and women, worried by the growing involvement of the Church in secular and political affairs, sought refuge in the deserts and wilderness where they might lead simple lives of prayer and contemplation. By the early 300s, however, such individual monasticism had given way to more organized monasteries - communities of monks and nuns, who supported each others' spiritual devotions through communal living and an equal sharing of the work necessary to sustain the community.

The development of monastic communities greatly expanded the ability of ordinary men and women to pursue lives of religious devotion, particularly in times of turmoil. During the collapse of the western empire and the German migrations, as the insecurity index rose, monastic life offered both spiritual and physical security. Monasteries also offered safe havens from which missionaries could work to convert the still pagan or heretical Germanic invaders to Christianity.

By the early 5th century, monastic communities had been established as far away as Ireland. According to tradition, for example, in the early 400s a Romano-British monk named Patrick helped convert the Irish to Christianity and established a series of monasteries. Patrick himself had been trained in the monastery at Lérins, Italy, which had been founded by monks from the eastern empire. As Roman influence retreated from northern Europe, Christianity increasingly revolved around the safe havens of the monasteries. From these communities, Irish monks and nuns carried the gospel message back to Britain and from there to much of northern Europe.

Irish missionaries had great success, particularly in northern Britain. Among the monastic communities they founded there was the so-called double monastery established at Whitby, which included both monks and nuns under the rule of an abbess. Saint Hilda, the founder and perhaps the most famous abbess of Whitby, was praised by an early chronicler for her learning and administrative skills:

“So great was her prudence that not only ordinary folk, but kings and princes used to come and ask her advice in their difficulties and take it. Those under her direction were required to make a thorough study of the Scriptures and occupy themselves in good works, to such good effect that many were found fitted for Holy Orders and the service of God’s altar.”[7]

In fact, Hilda may have modeled Whitby on a pattern established first in Ireland by St. Brigid at Kildare.

In addition to spreading Christianity, the monasteries of Ireland and their British offshoots kept alive the knowledge of the past. Monks lovingly copied the Gospels and other writings by hand on great sheets of scraped and cured sheepskin called vellum. With exquisite care they decorated the treasured writings with magnificent calligraphy in vibrant colors of blue and red and thin layers of gold. The monasteries also functioned as schools, where not only Latin but also Greek texts were taught. Irish monastic schools soon drew students from throughout western Europe.

To a large degree, German acceptance of Roman influences was made possible by the one great imperial institution to survive intact—the Church. In theory, the Church was organized along the lines of the Roman imperial administrative system: every diocese was headed by a bishop, and every province, made up of many dioceses, was headed by an archbishop. The bishop of Rome, who was called the pope, from the Latin word for “father,” was generally acknowledged as the head of the church – at least in the western provinces.

When the Roman imperial system failed in the western parts of the Empire, the Church took over. Soon, Church officials exercised secular as well as spiritual authority in many cities of the old imperial heartland, as bishops took over the functions that had been performed by imperial magistrates. Beyond the city walls, however, even the authority of the bishops did not, at first, run far.

Although the Church had generally survived the collapse of the Roman state thanks to the faith of its members, its continued existence as a unified institution was by no means certain. For one thing, most of the Germanic groups overrunning the western provinces were either still pagans or converts to the Arian form of Christianity the Church had branded heretical. Moreover, even as the official state religion of the empire, Christianity had not fully established itself beyond the walls of the empire's major cities, particularly in northwestern Europe.

North of the Alps in particular, Church organization was either non-existent or in a state of chaos; and most of the territories north of the Danube River had never been Christianized at all. Consequently, after the collapse of imperial authority, bishops often found themselves dependent on the local Germanic kings and warlords for their positions and their security. The pope's authority to appoint and remove bishops had not yet been fully accepted. Hoping to control the Church's power and influence for their own benefit, Germanic kings frequently appointed bishops from among their own families and supporters, or sold the appointments to the highest bidder.

Yet even as the Church increasingly found itself drawn into such local politics, often compromising its own moral and religious teachings, its message of salvation seemed more and more appropriate to the times. As peoples' lives became less and less secure, the church taught that earthly existence was only a step toward a better life to come. Not only did this message comfort the Christian Roman population, but in the 400s and 500s, it even began to move beyond the old Roman world. Both the survival of the organized Church and the spread of Catholic Christianity were largely due to the growth of a new movement in western Europe - monasticism.

The influence of monasticism. Christian monasticism had begun in the Eastern Empire, particularly in Egypt, in the late 200s, largely as a reaction to the success of Christianity and its acceptance by the Roman state. Individual men and women, worried by the growing involvement of the Church in secular and political affairs, sought refuge in the deserts and wilderness where they might lead simple lives of prayer and contemplation. By the early 300s, however, such individual monasticism had given way to more organized monasteries - communities of monks and nuns, who supported each others' spiritual devotions through communal living and an equal sharing of the work necessary to sustain the community.

The development of monastic communities greatly expanded the ability of ordinary men and women to pursue lives of religious devotion, particularly in times of turmoil. During the collapse of the western empire and the German migrations, as the insecurity index rose, monastic life offered both spiritual and physical security. Monasteries also offered safe havens from which missionaries could work to convert the still pagan or heretical Germanic invaders to Christianity.

By the early 5th century, monastic communities had been established as far away as Ireland. According to tradition, for example, in the early 400s a Romano-British monk named Patrick helped convert the Irish to Christianity and established a series of monasteries. Patrick himself had been trained in the monastery at Lérins, Italy, which had been founded by monks from the eastern empire. As Roman influence retreated from northern Europe, Christianity increasingly revolved around the safe havens of the monasteries. From these communities, Irish monks and nuns carried the gospel message back to Britain and from there to much of northern Europe.

Irish missionaries had great success, particularly in northern Britain. Among the monastic communities they founded there was the so-called double monastery established at Whitby, which included both monks and nuns under the rule of an abbess. Saint Hilda, the founder and perhaps the most famous abbess of Whitby, was praised by an early chronicler for her learning and administrative skills:

“So great was her prudence that not only ordinary folk, but kings and princes used to come and ask her advice in their difficulties and take it. Those under her direction were required to make a thorough study of the Scriptures and occupy themselves in good works, to such good effect that many were found fitted for Holy Orders and the service of God’s altar.”[7]

In fact, Hilda may have modeled Whitby on a pattern established first in Ireland by St. Brigid at Kildare.

In addition to spreading Christianity, the monasteries of Ireland and their British offshoots kept alive the knowledge of the past. Monks lovingly copied the Gospels and other writings by hand on great sheets of scraped and cured sheepskin called vellum. With exquisite care they decorated the treasured writings with magnificent calligraphy in vibrant colors of blue and red and thin layers of gold. The monasteries also functioned as schools, where not only Latin but also Greek texts were taught. Irish monastic schools soon drew students from throughout western Europe.

St. Benedict giving the Rule of the order

St. Benedict giving the Rule of the order

Yet while Irish missionaries played a significant role in carrying the Christian message and their own monastic model to Britain and other parts of western Europe, the man primarily responsible for the spread of monasticism in Europe, and with it Christianity, was a wealthy Roman, Saint Benedict of Nursia.

Around 529 Benedict established a monastery at Monte Cassino near Rome. Although influenced by earlier models, he wrote his own set of rules to govern monastic life. The Benedictine Rule eventually became a fundamental pattern for Catholic monasteries.

Benedict regulated almost every aspect of monastic life, from what the monks should wear, to how much they could eat:

“Let one pound of bread suffice for a day, whether there be one principal meal, or both dinner and supper. . . . All must abstain from the flesh of four-footed beasts, except the delicate and the sick.”[9]

INTERNET RESOURCES:

St. Benedict, Monte Cassino

The Rule described the virtues that monks should develop, including humility and obedience to God, pope, and abbot. It also offered detailed instructions about the monks’ rounds of prayer, readings, and singing that began long before daybreak. It even regulated their hours of sleep, manual work, and meals. In addition to prayer, the monks performed other roles in their local communities, acting for example as librarians, estate managers, and secretaries to kings. Some began schools to keep education and learning alive. They also undertook missionary efforts. As the Benedictines spread throughout Western Europe, they preached the official doctrines of the Roman Church and reinforced the pope’s authority.

Around 529 Benedict established a monastery at Monte Cassino near Rome. Although influenced by earlier models, he wrote his own set of rules to govern monastic life. The Benedictine Rule eventually became a fundamental pattern for Catholic monasteries.

Benedict regulated almost every aspect of monastic life, from what the monks should wear, to how much they could eat:

“Let one pound of bread suffice for a day, whether there be one principal meal, or both dinner and supper. . . . All must abstain from the flesh of four-footed beasts, except the delicate and the sick.”[9]

INTERNET RESOURCES:

St. Benedict, Monte Cassino

The Rule described the virtues that monks should develop, including humility and obedience to God, pope, and abbot. It also offered detailed instructions about the monks’ rounds of prayer, readings, and singing that began long before daybreak. It even regulated their hours of sleep, manual work, and meals. In addition to prayer, the monks performed other roles in their local communities, acting for example as librarians, estate managers, and secretaries to kings. Some began schools to keep education and learning alive. They also undertook missionary efforts. As the Benedictines spread throughout Western Europe, they preached the official doctrines of the Roman Church and reinforced the pope’s authority.

Pope Gregory the Great

Pope Gregory the Great

Pope Gregory the Great. One of the most effective advocates of both papal authority and expansion of the church was Pope Gregory I, later called the Great. Gregory, who had himself been a Benedictine monk, fully supported the monastic missionary movement. To assist the movement, he adopted a policy of encouraging conversion by absorbing some pagan customs and practices into Christianity. In 601, for example, he sent a message advising Bishop Augustine in England of the policy:

“We have been giving careful thought to the affairs of the English, and have come to the conclusion that the temples of the idols among that people should on no account be destroyed. The idols are to be destroyed, but the temples themselves are to be aspersed [sprinkled] with holy water, altars set up in them, and relics deposited there. . . . In this way, we hope that the people, seeing that their temples are not destroyed, may abandon their error and, flocking more readily to their accustomed resorts, may come to know and adore the true God. . . . For it is certainly impossible to eradicate all errors from obstinate minds at one stroke, and whoever wishes to climb to a mountain top climbs gradually step by step, and not in one leap.”

Under the influence of leaders like Gregory, the traditions and institutions of Christianity and the western parts of the old Roman Empire interacted with Germanic culture to produce a new civilization, distinct from that of the remaining eastern Empire - Latin Christendom.

The Franks

One of the church’s great hopes for Latin Christendom was the establishment of a universal Catholic Church allied with a universal state. Toward this end, church leaders tried their best to convert the Germanic invaders. Initially they had little success, since the first wave of Germanic tribes had converted to Arian Christianity rather than Catholicism before entering the empire. As pagan tribes followed in the wake of the Ostrogoths and Visigoths, however, church authorities saw fresh opportunities to achieve their goals. By the end of the 400s, the pagan Franks of northern Gaul had emerged as the most powerful of the Germanic kingdoms and the best potential allies for the church. Under their leader Clovis and his descendants, they conquered the neighboring Visigoths and Burgundians and created a great empire that covered much of Gaul.

“We have been giving careful thought to the affairs of the English, and have come to the conclusion that the temples of the idols among that people should on no account be destroyed. The idols are to be destroyed, but the temples themselves are to be aspersed [sprinkled] with holy water, altars set up in them, and relics deposited there. . . . In this way, we hope that the people, seeing that their temples are not destroyed, may abandon their error and, flocking more readily to their accustomed resorts, may come to know and adore the true God. . . . For it is certainly impossible to eradicate all errors from obstinate minds at one stroke, and whoever wishes to climb to a mountain top climbs gradually step by step, and not in one leap.”

Under the influence of leaders like Gregory, the traditions and institutions of Christianity and the western parts of the old Roman Empire interacted with Germanic culture to produce a new civilization, distinct from that of the remaining eastern Empire - Latin Christendom.

The Franks

One of the church’s great hopes for Latin Christendom was the establishment of a universal Catholic Church allied with a universal state. Toward this end, church leaders tried their best to convert the Germanic invaders. Initially they had little success, since the first wave of Germanic tribes had converted to Arian Christianity rather than Catholicism before entering the empire. As pagan tribes followed in the wake of the Ostrogoths and Visigoths, however, church authorities saw fresh opportunities to achieve their goals. By the end of the 400s, the pagan Franks of northern Gaul had emerged as the most powerful of the Germanic kingdoms and the best potential allies for the church. Under their leader Clovis and his descendants, they conquered the neighboring Visigoths and Burgundians and created a great empire that covered much of Gaul.

Tomb of Clovis I at the Basilica of St Denis

Tomb of Clovis I at the Basilica of St Denis

The Merovingians. Clovis established the Merovingian dynasty, which took its name from Merovech,[12] one of his ancestors. According to tradition, Clovis converted from paganism to Catholic Christianity in 496, much to the delight of church leaders. It was a shrewd move that gained him the support not only of the church but also of the old Roman aristocracy. Clovis hoped to use the church to help him run his new empire. Germanic tribal society had never developed the administrative institutions necessary to run an urban society like that of the Romans. Although the urban society of the old empire had already begun to fade in Clovis's new realm, the size of the Merovingian domain made its administration difficult. For its part, the church was more than willing to supply administrators and advice to the new Germanic king.

Clovis’s empire did not last long, however, partly due to his allegiance to Germanic inheritance customs. On his deathbed in 511, Clovis divided his kingdom among his four sons as custom decreed. Plagued by civil war, the growing power of the Frankish nobility, and challenges from Byzantine and invading Germanic forces from the east, Clovis’s heirs could not maintain control of the realm. By the 700s, real power in the Frankish empire rested with the most important official of the king's household, the mayor of the palace. The Merovingian kings, like the Abbasids in Baghdad, had become mere figureheads.

The Carolingians. In 732 the mayor Charles Martel gained the church’s favor when he defeated a Muslim raiding party near the French town of Tours. Many hailed it as a great Christian victory, and Charles achieved great prestige. However, when the pope called for his aid against the Lombards in Italy, the mayor refused. His son, Pepin, later answered a similar call only after the pope had agreed that he should depose the last Merovingian king and assume the throne himself. In 751, the pope personally traveled to France to proclaim Pepin "king by the grace of God." Pepin’s coronation launched what came to be called the Carolingian dynasty.

In 754 and 756, Pepin achieved victories against the Lombards. He turned the lands he captured in central Italy over to the pope. This gift, called the Donation of Pepin, created the Papal States. The gift made the papacy a secular as well as a spiritual power and further strengthened the alliance between the Carolingians and the church.

[BIO] The Carolingian dynasty took its name from Pepin's son Carolus Magnus, or Charlemagne (Charles the Great). Charlemagne was born in 742. Although a deeply religious and highly intelligent man, he had little formal education. Nevertheless, he became an outstanding ruler. Charlemagne wanted to establish an empire with the power and glory of the old Roman Empire. On his father’s death in 768, however, the kingdom was divided between Charlemagne and his brother Carloman. Not until his brother died in 771 was Charlemagne able to assume sole power as king of the Franks, and pursue his ambition. He soon took as his motto the Latin phrase, Renovatio imperi romani, "Renewal of the Roman Empire."

Like many kings of his day, Charlemagne spent much of his life at war. He defeated the Lombards in Italy, as well as the Saxons in northern Germany and the Avars in central Europe. Although unable to evict the Muslims from Spain, he drove them across the Pyrenees and established a buffer zone called the Spanish March. Eventually, Charlemagne controlled most of western Europe.

Charlemagne divided his realm into counties, ruled by counts. Dukes, whose titles probably derived from the old Roman office of dux bellorum, or “leader of war,” ruled the border regions, known as marches. Each of these nobles was directly responsible to Charlemagne and carried out his commands in their own territories. In support of these arrangements, on Christmas Day in the year 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne "Emperor of the Romans." The ideal of a universal empire allied with the universal church seemed close at hand.

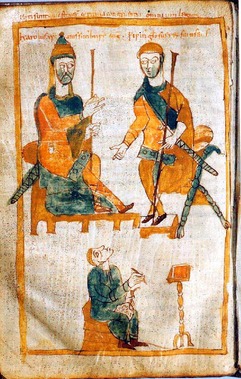

Charlemagne (left) and his son Pippin the Hunchback (right).

Tenth-century copy of a lost original from about 830

The Carolingian renaissance. Charlemagne did his best to live up to the image of a Roman emperor. He was admired for his skills as a warrior as well as for being a devout Christian. His secretary Einhard has left a glimpse of the man:

“Charles was large and strong, and of lofty stature . . . ; the upper part of his head was round, his eyes very large and animated, nose a little long, hair fair, and face laughing and merry. Thus his appearance was always stately and dignified . . . although his neck was thick and somewhat short, and his belly rather prominent. . . . His gait was firm, his whole carriage manly, and his voice clear, but not so strong as his size led one to expect.” [14]

Charlemagne was particularly interested in education. He established a palace school for young nobles, where scholars from throughout western Europe came to teach. He also encouraged the establishment of schools at monasteries and cathedrals across Europe to give priests a basic education. Many scholars call this revival of learning the Carolingian renaissance,[15] or rebirth.

Despite Charlemagne's efforts, his empire did not last long after his death in 814. During the reign of his one surviving son, Louis the Pious, civil war wracked the kingdom as Louis’ sons contested their father’s own succession plans. The civil wars continued even after Louis’ death in 840. In 843 his sons finally signed the Treaty of Verdun, which divided the empire into a western, a middle, and an eastern kingdom. The empire began to crumble. Although short-lived, however, the Frankish empires kept alive the idea of a universal state allied to the universal church.

Renewed Invasions

Charlemagne's empire splintered not only because of internal feuds and divisions, but also because waves of invaders once again swarmed into the empire from every direction. Among the most dangerous of the invaders were the Vikings, Magyars, and Muslims.

Vikings. In the late 700s and early 800s—for reasons that scholars still dispute—the peoples of Scandinavia burst onto the stage of history. While the Germans had begun gradually to give in to Christianity and the civilizing influence of the old Roman world, the Vikings remained both pagan and warlike. In long shallow-draft ships, driven by oars and a single large square sail, the Vikings swept into Europe like a violent lightning storm. For nearly 200 years, wave after wave of raiders sailed south every spring, returning to their northern homes before the icy gales of winter had set in, or when their ships had been filled with plunder and slaves.

Very quickly, however, many Vikings began to winter in the southlands, and to settle permanently in lands they had formerly raided. Large Viking settlements were established in England, for example, known as the Danelaw, while across the Channel the Viking chief Rollo claimed what became known as Normandy in northern France.[16] To the east, they sailed down the rivers of Russia as far as the Black Sea. To the west, they attacked not only the British Isles and northern France, but also Ireland and Spain, and even sailed as far as North America. In the south, some raided the Mediterranean.

Everywhere, Viking raiders struck terror in the hearts of their victims, for their attacks were swift and savage. Monks were favorite targets. To protect themselves, Irish monks built tall stone towers with doors high off the ground. At the first sign of Viking ships, the monks would flee to the towers and draw up the ladders. Even in times of relative peace, their prayers ended more often than not with the heartfelt plea: “and from the wrath of the Vikings, dear Lord, deliver us.” In other parts of Europe, too, local lords built stone castles into which villagers might flee for safety. As the raiders began to settle, however, they turned increasingly from raiding to long-distance commerce and trade.

Magyars. At the end of the 800s, a new wave of invasions from the east once again terrorized Europe. Magyar tribes crossed the Danube and moved westward through Europe, attacking villages and taking peasants to sell in eastern slave markets. In many early attacks on isolated settlements, the Magyars killed or carried off everyone in the villages. Convinced that such brutal raiders must be returning Huns, people began to call them Hungarians. North of the Magyars, Slavic tribes also settled in Europe.

Muslims. Meanwhile, in the south, Muslim forces attacked from North Africa and Spain in the 800s and 900s. Though as brutal as those of the Magyars and the Vikings, their attacks were equally frightening. In 846, for example, Muslim forces captured and sacked Rome before retreating. In comparison with the richness of the Islamic world, however, northern Europe offered little to interest the Arabs.

Nevertheless, as Muslim fleets swept the Mediterranean clear of Byzantine shipping, Italy was suddenly cut off from the Eastern Empire. Deprived of eastern support, the popes had little choice but to turn to the Franks for protection. As a result, the balance of power in Latin Christendom shifted to the Frankish homeland in northwestern Europe.

Section 1 Review

Identify. noble, freeman, pope, Benedictine Rule, Gregory the Great, Latin Christendom, Charles Martel, Pepin, Charlemagne, Carolingian renaissance, Treaty of Verdun.

Locate. Tours, Pyrenees Mountains, Scandinavia

1. Main Idea. How did the Roman church provide Europe with a sense of unity?

2. Main Idea. How did Charlemagne's empire change western Europe?

3. Geography. How did geography help raiders, such as the Vikings, Magyars, and Muslims invade Europe?

4. Writing to Explain. Explain how life in the Germanic tribes changed after the fall of Rome.

5. Analyzing. Why might people in Europe after the fall of Rome have wanted to establish European unity?

The Carolingians. In 732 the mayor Charles Martel gained the church’s favor when he defeated a Muslim raiding party near the French town of Tours. Many hailed it as a great Christian victory, and Charles achieved great prestige. However, when the pope called for his aid against the Lombards in Italy, the mayor refused. His son, Pepin, later answered a similar call only after the pope had agreed that he should depose the last Merovingian king and assume the throne himself. In 751, the pope personally traveled to France to proclaim Pepin "king by the grace of God." Pepin’s coronation launched what came to be called the Carolingian dynasty.

In 754 and 756, Pepin achieved victories against the Lombards. He turned the lands he captured in central Italy over to the pope. This gift, called the Donation of Pepin, created the Papal States. The gift made the papacy a secular as well as a spiritual power and further strengthened the alliance between the Carolingians and the church.

[BIO] The Carolingian dynasty took its name from Pepin's son Carolus Magnus, or Charlemagne (Charles the Great). Charlemagne was born in 742. Although a deeply religious and highly intelligent man, he had little formal education. Nevertheless, he became an outstanding ruler. Charlemagne wanted to establish an empire with the power and glory of the old Roman Empire. On his father’s death in 768, however, the kingdom was divided between Charlemagne and his brother Carloman. Not until his brother died in 771 was Charlemagne able to assume sole power as king of the Franks, and pursue his ambition. He soon took as his motto the Latin phrase, Renovatio imperi romani, "Renewal of the Roman Empire."

Like many kings of his day, Charlemagne spent much of his life at war. He defeated the Lombards in Italy, as well as the Saxons in northern Germany and the Avars in central Europe. Although unable to evict the Muslims from Spain, he drove them across the Pyrenees and established a buffer zone called the Spanish March. Eventually, Charlemagne controlled most of western Europe.

Charlemagne divided his realm into counties, ruled by counts. Dukes, whose titles probably derived from the old Roman office of dux bellorum, or “leader of war,” ruled the border regions, known as marches. Each of these nobles was directly responsible to Charlemagne and carried out his commands in their own territories. In support of these arrangements, on Christmas Day in the year 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne "Emperor of the Romans." The ideal of a universal empire allied with the universal church seemed close at hand.

Charlemagne (left) and his son Pippin the Hunchback (right).

Tenth-century copy of a lost original from about 830

The Carolingian renaissance. Charlemagne did his best to live up to the image of a Roman emperor. He was admired for his skills as a warrior as well as for being a devout Christian. His secretary Einhard has left a glimpse of the man:

“Charles was large and strong, and of lofty stature . . . ; the upper part of his head was round, his eyes very large and animated, nose a little long, hair fair, and face laughing and merry. Thus his appearance was always stately and dignified . . . although his neck was thick and somewhat short, and his belly rather prominent. . . . His gait was firm, his whole carriage manly, and his voice clear, but not so strong as his size led one to expect.” [14]

Charlemagne was particularly interested in education. He established a palace school for young nobles, where scholars from throughout western Europe came to teach. He also encouraged the establishment of schools at monasteries and cathedrals across Europe to give priests a basic education. Many scholars call this revival of learning the Carolingian renaissance,[15] or rebirth.

Despite Charlemagne's efforts, his empire did not last long after his death in 814. During the reign of his one surviving son, Louis the Pious, civil war wracked the kingdom as Louis’ sons contested their father’s own succession plans. The civil wars continued even after Louis’ death in 840. In 843 his sons finally signed the Treaty of Verdun, which divided the empire into a western, a middle, and an eastern kingdom. The empire began to crumble. Although short-lived, however, the Frankish empires kept alive the idea of a universal state allied to the universal church.

Renewed Invasions

Charlemagne's empire splintered not only because of internal feuds and divisions, but also because waves of invaders once again swarmed into the empire from every direction. Among the most dangerous of the invaders were the Vikings, Magyars, and Muslims.

Vikings. In the late 700s and early 800s—for reasons that scholars still dispute—the peoples of Scandinavia burst onto the stage of history. While the Germans had begun gradually to give in to Christianity and the civilizing influence of the old Roman world, the Vikings remained both pagan and warlike. In long shallow-draft ships, driven by oars and a single large square sail, the Vikings swept into Europe like a violent lightning storm. For nearly 200 years, wave after wave of raiders sailed south every spring, returning to their northern homes before the icy gales of winter had set in, or when their ships had been filled with plunder and slaves.

Very quickly, however, many Vikings began to winter in the southlands, and to settle permanently in lands they had formerly raided. Large Viking settlements were established in England, for example, known as the Danelaw, while across the Channel the Viking chief Rollo claimed what became known as Normandy in northern France.[16] To the east, they sailed down the rivers of Russia as far as the Black Sea. To the west, they attacked not only the British Isles and northern France, but also Ireland and Spain, and even sailed as far as North America. In the south, some raided the Mediterranean.

Everywhere, Viking raiders struck terror in the hearts of their victims, for their attacks were swift and savage. Monks were favorite targets. To protect themselves, Irish monks built tall stone towers with doors high off the ground. At the first sign of Viking ships, the monks would flee to the towers and draw up the ladders. Even in times of relative peace, their prayers ended more often than not with the heartfelt plea: “and from the wrath of the Vikings, dear Lord, deliver us.” In other parts of Europe, too, local lords built stone castles into which villagers might flee for safety. As the raiders began to settle, however, they turned increasingly from raiding to long-distance commerce and trade.

Magyars. At the end of the 800s, a new wave of invasions from the east once again terrorized Europe. Magyar tribes crossed the Danube and moved westward through Europe, attacking villages and taking peasants to sell in eastern slave markets. In many early attacks on isolated settlements, the Magyars killed or carried off everyone in the villages. Convinced that such brutal raiders must be returning Huns, people began to call them Hungarians. North of the Magyars, Slavic tribes also settled in Europe.

Muslims. Meanwhile, in the south, Muslim forces attacked from North Africa and Spain in the 800s and 900s. Though as brutal as those of the Magyars and the Vikings, their attacks were equally frightening. In 846, for example, Muslim forces captured and sacked Rome before retreating. In comparison with the richness of the Islamic world, however, northern Europe offered little to interest the Arabs.

Nevertheless, as Muslim fleets swept the Mediterranean clear of Byzantine shipping, Italy was suddenly cut off from the Eastern Empire. Deprived of eastern support, the popes had little choice but to turn to the Franks for protection. As a result, the balance of power in Latin Christendom shifted to the Frankish homeland in northwestern Europe.

Section 1 Review

Identify. noble, freeman, pope, Benedictine Rule, Gregory the Great, Latin Christendom, Charles Martel, Pepin, Charlemagne, Carolingian renaissance, Treaty of Verdun.

Locate. Tours, Pyrenees Mountains, Scandinavia

1. Main Idea. How did the Roman church provide Europe with a sense of unity?

2. Main Idea. How did Charlemagne's empire change western Europe?

3. Geography. How did geography help raiders, such as the Vikings, Magyars, and Muslims invade Europe?

4. Writing to Explain. Explain how life in the Germanic tribes changed after the fall of Rome.

5. Analyzing. Why might people in Europe after the fall of Rome have wanted to establish European unity?